By Terry Sovil from the August 2010 Edition

(1648-1695)

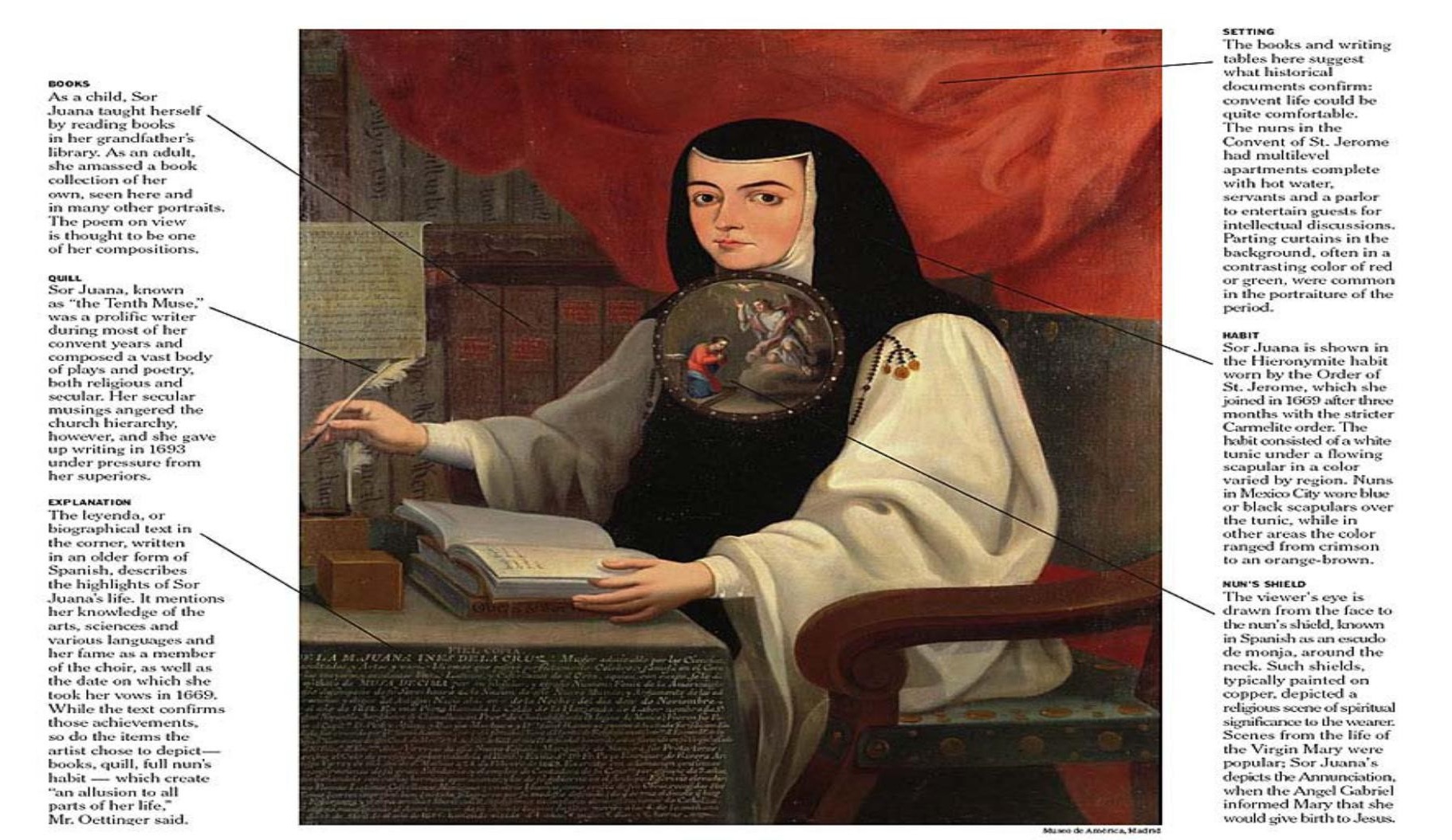

This street in Manzanillo is near the Country Club in El Jabalí. Sor (Sister) Juana (say “wanna”) Inés de La Cruz lived from 1648 or 51 to 1695. She has a face you see regularly! Look at a 200 peso bill where her face and quill are shown beside works of Poesias Liricas (lyric poetry) for which she is well known. She was at the very beginning of Mexican Literature and is known for her writing.

Juana was a precocious child born on 12 November 1651 or on 17 April 1648 depending on your source. Her birth date is probably questionable since she was born as the illegitimate daughter of a Mexican Creole mother and a Spanish soldier at a time when bloodlines meant everything for class and status.

She was gifted, characterized as a rebel, and by the tender age of three had learned to read and write. She understood numbers by age five and composed a poem by age eight. By age thirteen she was teaching Latin and had mastered Greek logic. It is said that she learned lessons with help from her sister. She also learned and wrote a few short poems in the Nahuatl language. This was not the child you wanted asking you “why”.

Raised by her maternal grandfather her reputation as a rebel started early by doing things forbidden for girls during that period. Juana used to hide in an area of the chapel reading books from her grandfather’s adjoining library. She was sent to Mexico City to live with relatives. There she asked for parental permission to disguise as a male so she could enter the University. Permission denied; she continued studies on her own.

Juana appeared before the Vice-regal Court and a new viceroy sent from Spain. She was well liked and asked to serve as a companion to the Viceroy’s wife, Maria Leonor Carreto, called “Laura” in Juana’s poems. Wishing to test Juana, the viceroy brought in several legal scholars, philosophers, poets and theologians. Juana had to answer difficult questions impromptu and explain complex scientific and literary subjects. Her performance impressed all present and increased her reputation. Her literary work began to gain fame in Mexico.

Juana decided to become a nun as a way for her to legitimately continue her studies. On 14th August 1667, she entered a Carmelite convent but it was far too stiff and austere for her. She moved to the order of Jerome at the monastery of Santa Paula and on 24 February 1669 took her final vows and became Sister Juana Inés de la Cruz.

Totally intrigued by paintings with that “thing” around her neck caused serious internet research producing articles regarding her as an early feminist pioneer. She had stated the case for women’s equality before it ever had a name or a following. She wrote about freedom and a woman’s right to respect as a human being. She wrote “Hombres Necios” (foolish men) and criticized social standards of her day. She saw hypocrisy in the public condemnation of prostitutes by men that privately paid them for services. “Who sins more, she who sins for pay? Or he who pays for sin?”

Juana wrote a romantic comedy about a brother and sister entangled in webs of love and jealousy. Her writings and thoughts expressed out loud were considered dangerous by the Church. Anyone challenging current social values could be branded as a heretic. At that time the church silenced critics by false accusations, property seizure, exile and even imprisonment, torture or murder. Juana had support in powerful Spanish court mentors and she was widely read in Spain where they called her “the Tenth Muse”.

What about that “thing” around her neck? High resolution photos were enlarged to get a better look at the actual image. That same image is reproduced everywhere, including a statue of her in Spain. The painting was done in

1772 by Andrés de Islas 77 years after her death and was based on an earlier portrait by Juan de Miranda.

Several accounts claim that Juana and the Viceroy’s wife, Maria Leonor Carreto, were lovers. A modern independent film, “I, The Worst of All” shows them exchanging a kiss. Many accounts claim the Viceroy’s wife gave Juana a miniature portrait of herself that she always wore around her neck. One internet photo of the painting with annotations came up. That description says it is an “escudo de monja” or a nun’s shield. Painted on copper they depict a religious scene important to the person wearing it. According to the annotation this image depicts the “Angel Gabriel telling Mary she would give birth to Jesus”. Is the image around her neck in the painting an accurate representation or was some censoring done by an artist? Little is known about Juana’s last few years. It is known that the church moved to discredit her and she seems to have either decided to be silent rather than risk further censure or was forced to be silent. There is no hard evidence of her renouncing her writing or themes but there are some that support her agreement to self – humiliation. She did sell her beloved extensive library of over 4,000 books and her scientific instruments. Only a few of her writings remain, including a “Complete Works” that were saved by the Viceroy’s wife. She died in a plague that swept her convent and city on the morning of April 17, 1965.

Download the full edition or view it online

—

Terry is a founding partner and scuba instructor for Aquatic Sports and Adventures (Deportes y Aventuras Acuáticas) in Manzanillo. A PADI (Professional Association of Dive Instructors) Master Instructor in his 36th year as a PADI Professional. He also holds 15 Specialty Instructor Course ratings. Terry held a US Coast Guard 50-Ton Masters (Captain’s) License. In his past corporate life, he worked in computers from 1973 to 2005 from a computer operator to a project manager for companies including GE Capital Fleet Services and Target. From 2005 to 2008, he developed and oversaw delivery of training to Target’s Loss Prevention (Asset Protection) employees on the West Coast, USA. He led a network of 80+ instructors, evaluated training, performed needs assessments and gathered feedback on the delivery of training, conducted training in Crisis Leadership and Non-Violent Crisis Intervention to Target executives. Independently, he has taught hundreds of hours of skills-based training in American Red Cross CPR, First Aid, SCUBA and sailing and managed a staff of Project Managers at LogicBay in the production of multi-media training and web sites in a fast-paced environment of artists, instructional designers, writers and developers, creating a variety of interactive training and support products for Fortune 1000 companies.

You must be logged in to post a comment.