By David Fitzpatrick from the September 2010 Edition

Part III: The DÉNOUEMENT

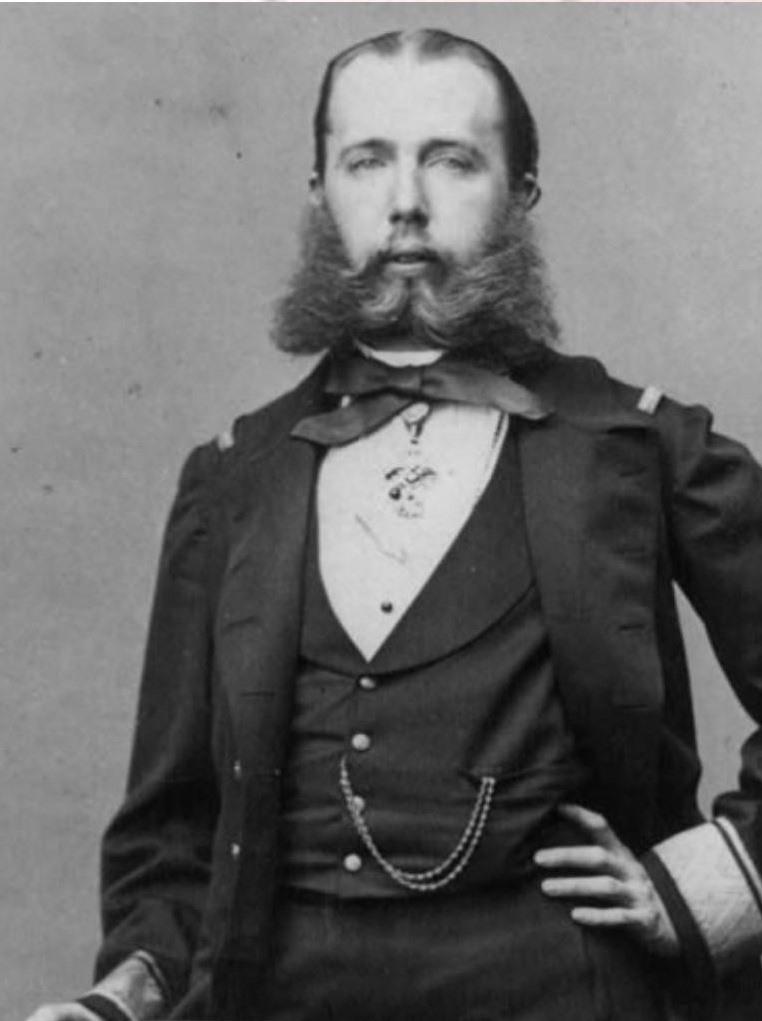

(In the previous two issues: Napoléon III, Emperor of the French invaded Mexico and attempted to install a « puppet » Emperor in Mexico City. His selection for the throne, the Archduke Maximilian of Austria seemed an ideal choice, given the long common history of Spain, Latin America, and the House of Habsburg. But Maximilian proved to be his own man, not beholden to the French. His idealistic character, however, was ill-adapted to the chaotic political situation in which he found himself: his liberal reforms alienated the right, which was his natural constituency, while the left would never accept a monarchy under any circumstances. Moreover the French, the source of his military support, soon lost interest in Mexico when Maximilian refused to cede the state of Sonora to them. The new Emperor soon found himself politically isolated.)

The reign of the new Emperor began in an atmosphere of euphoria. An immense crowd met the boat arriving at Veracruz and the general rejoicing lasted long into the night. The downtrodden population, happy at the end of the former, abusive régime, placed all its hopes in the young, idealistic emperor.

With the cheers of the populace still ringing in their ears, the imperial couple moved into the Chapultepec Palace high on a hilltop near Mexico City. The palace was completely renovated and major public works were begun to improve the city. A wide boulevard was pierced through the densely populated center of the city to be named “Paseo de la Emperatriz” (now called “Paseo de la Reforma”).

Maximilian set about immediately to put his social programme into action. Full of progressive ideas, he was appalled at the living condition of the peons and their near-starvation existence. He ended the practice whereby peons could be bought and sold for their debts and simply cancelled all debts above 10 pesos owed by peons. Corporal punishment in all its forms was outlawed. He also began a program of land reform with the intention of breaking up the great haciendas and giving small plots of land to the peasants, but this was never completely carried through and no comprehensive redistribution of land occurred until the twentieth century.

But Maximilian had walked into the middle of a civil war. The fighting begun by Napoléon III’s invasion had never ended. Benito Juarez was still operating a rival “government in exile” principally in Chihuahua. He did not recognize the new régime, considering Maximilian to be merely a puppet of Napoléon. So the Emperor was attempting to enact a major social program and function as a war-time ruler at the same time. He hoped that his aggressive program for social justice would help to effect a reconciliation with Juarez and the liberals and even offered Juarez the post of Prime Minister in his government. But this was a vain hope. The left would never accept a monarchy under any conditions and, from a political point of view, the progressive policies served only to alienate the right.

In addition, the military situation was acute. The Régime had managed to keep at least some support from conservative elements among the ruling class and a portion of the armed forces was loyal to Maximilian. But his principal military force was the French army which had maintained a sizeable presence in Mexico.

In 1865, political events in Europe turned the attention of Napoléon and the general population of France to other matters and opposition to the Mexican war began to mount. Moreover, Maximilian’s stubborn independence, particularly his refusal to cede Sonora to France had exasperated Napoléon, who had also believed he would have a “puppet régime” in Mexico.

When Napoléon withdrew his troops in late 1865, Maximilian’s military position was no longer tenable. The few Mexican troops who remained loyal to him could never hope to prevail against Juarez and, in fact, the generals warned the Emperor that it would not be safe for him to set foot outside Mexico City.

At the same time, the Americans, who had kept their distance from events in Mexico while engaged in their own Civil War, now found themselves free to turn their attention southwards and, invoking the Monroe Doctrine, began to make plans to send troops into Mexico. In the end, no invasion ever materialized, but the American military stationed in Texas adopted a practice of “forgetting” large quantities of arms, on a daily basis, right on the border between El Paso and Ciudad Juarez. These arms, of course, greatly strengthened the cause of the Republicans.

In February 1867, Maximilian marched to Queretaro with the small force of 8,000 Mexican soldiers who remained at his command. Here, he was prepared to make a last stand against the advancing Republicans. However, one of his generals, having secretly gone over to Juarez, opened the gates of the fortress and handed the Emperor over to the Republican forces.

Maximilian and the last two generals who had remained with him were tried for treason and sentenced to be executed by firing squad. Many governments around the world wrote to Juarez requesting that the execution not be carried out. But Juarez believed it was necessary to make the point that Mexico would not tolerate interventions on its territory by foreign forces.

On June 19, 1867, Maximilian was executed, shouting “Viva Mexico! Viva la Independencia!”

There are many who have seen this episode as a tragic loss for Mexico. If a comprehensive progressive social program and the establishment of democratic political institutions, relatively free of corruption had been put in place in the middle of the 19th century, Mexican history in the 20th century might have been very different indeed.

The most lasting effect of his brief rule is Avenida Reforma, an important street in Mexico City that he had ordered built.

Download the full edition or view it online

You must be logged in to post a comment.