By Kirby Vickery from the January 2017 Edition

Although the Aztecs didn’t have Christmas, New Years (as we know it), Kwanza or any other modern or ancient ‘old world’ holidays and festivals that fell into, not only December, but the entire Western year, they had plenty of their own and I thought that we could rummage through a few of them to show that their spiritual and societal celebrations were not all full of blood and sacrifice, although some were at the beck and call of the Priest Class.

The first of three rain festivals for Tlaloc, their Rain God, was celebrated at the beginning of what we call February, which was the beginning of their agricultural year. There would be a priest or shaman to carry out the religious rituals which were designed to encourage rainfall. What type of rituals, you may ask? Please remember that the Aztec people believed that they were at the mercy of their gods, all of whom doted on a steady supply of sacrifice.

The second rain festival was offered to Tlaloc, as well as all the lesser rain gods, in March, once flowers had begun to bloom. The significance was as it is worldwide today, a celebration of the rebirth of life.

A third Aztec rain festival was celebrated in autumn, in order to again encourage rainfall. At the third rain festival, Aztec people formed shapes of small mountains and images of the god, Tla loc, as he was thought to live on a high mountain.

loc, as he was thought to live on a high mountain.

Cuauhtémoc was the last emperor of the Aztecs, whose memory is honoured every year during a celebration held in front of his statue on Paseo de la Reforma in Mexico City in August.

In this Aztec festival, the story of his life is told, detailing the struggle against the Spaniards, both in native Indian languages and in Spanish, while Conchero dancers perform their world-famous dances, wearing feathered headdresses trimmed with mirrors and beads.

They carry with them images of Jesus Christ and many saints to represent the blending of Aztec and Spanish cultures. Most of these Conchero groups consist of 50 or more dancers, each performing in his own rhythm and to his own accompaniment. The pace of the dance performance rises gradually until it reaches a sudden climax, which is followed by a moment of silence.

The Emperor Cuauhtémoc, in his words, is honoured for his “Bold and intimate acceptance of death”.

The Aztec calendar divided the year into 18 months of 20 days each, plus a five-day “unlucky” period. The Aztecs also knew a ritualistic period of 260 days, made up of 13 months with 20 named days in each. When one cycle was superimposed on the other, a “century” of 52 years resulted.

At the end of each of these 52-year cycles, the Aztecs were scared that the world would come to an end, therefore the most impressive and important of all festivals was held in these periods. Known as the New Fire Ceremony, this Aztec festival involved the putting out of the old altar fire and the lighting of a new one, as a symbol of the new cycle of life, represented by the dawning of the new era.

On the day of the New Fire Ceremony, all the fires in the Valley of Mexico were extinguished before sundown. Great masses of Aztec people journeyed from out of Mexico City to a temple several miles away on the Hill of the Star. On this hill, the priests lingered, waiting for a celestial sign coming from any direction as the firmament of the stars could be observed quite well from this spot. The sign would signify whether the world would end or whether a new cycle would begin.

The essence of this ritual was realized when the constellation, known as the Pleiades, passed the zenith, enabling life to go on as it had. (The Pleiades is a cluster of proto stars which is hard to look at straight on. There are seven of them, also known as The Seven Sisters, of which five can be seen with the naked eye. They have also become the symbol of the Subaru Automobile Company.) Had it failed to do so, the sun, the stars and other celestial bodies would change into ferocious beasts that would descend to the earth and devour all the Aztecs. Then an earthquake would finish the destruction. In each year, once a favorable interpretation of the celestial signal was made, burning torch-light were carried by runners all through the valley to rekindle the fires in each house.

This led to the New Fire Ceremony Morning at Chalmita, celebrated on the 280th day of the Aztec year, at end of 14th month, called the Quecholli Festival.

Mixcoatl, also known as the Cloud Serpent, was the Aztec deity of the chase, possessing the features of a deer or rabbit. He was associated with the morning star. One of the four creators of the world, he set a fire from sticks, enabling the creation of humans.

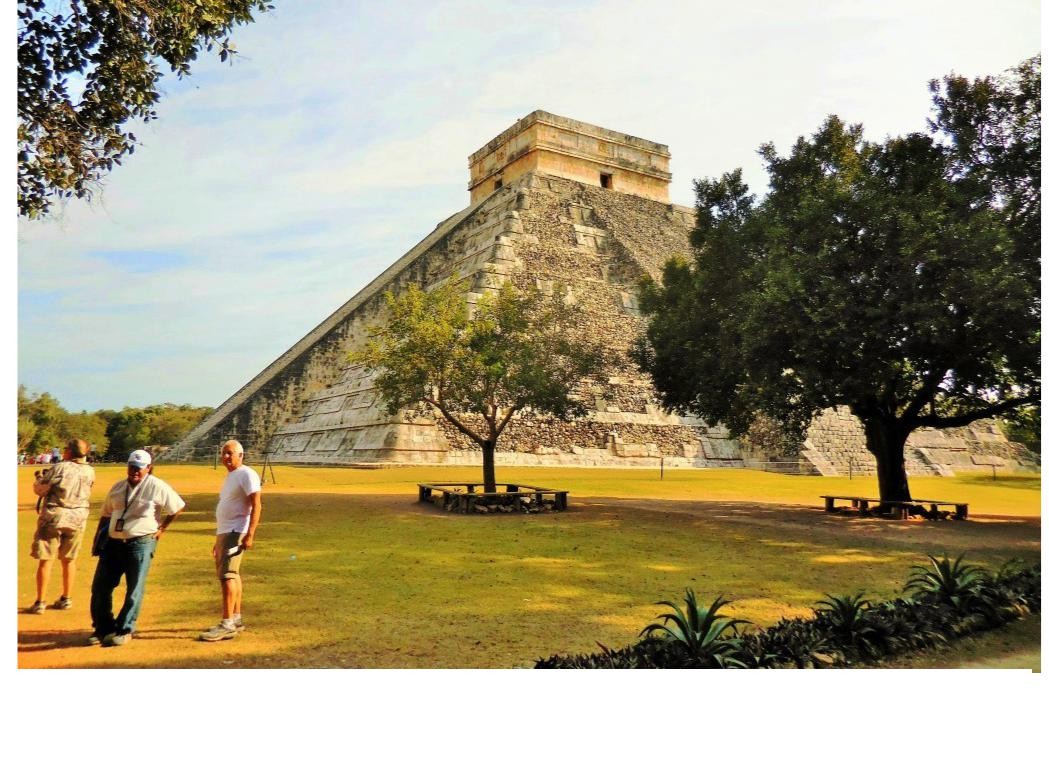

The Vernal Equinox was celebrated at the Chichén Itzá Festival on the 21st of March. In each year, on the Vernal Equinox, a beam of sunlight, as it hits the great El Castillo pyramid, brings into life a shadowy form that creates the illusion of a huge serpent slithering down its side. The Aztecs held that this serpent was the feathered snake god, Quetzalcoatl.

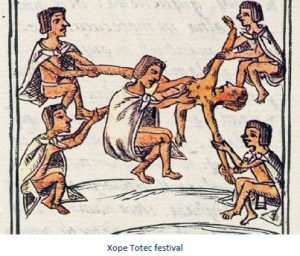

The festival of Xipe Totec at El Castillo Pyramid at Chichén Itzá celebrates the war-god wearing a human skin. His festival, known as Tlacaxipehualiztli, was held in March.

Aztec warriors took the festival of Xipe Totec for an excellent opportunity to mimic the god himself. Slaughtering their prisoners of war, also cutting their hearts out, they removed their skins and wore them for the entire 20-day month. They would fight mock battles, after which they would dispose of the rot-ting skins of the slaughtered in caves or holes in the ground.

Festival of Xilonen was a celebration honouring the goddess of maize. It was celebrated for eight days, beginning on the 22nd of June. Xilonen, also known as Chicomecoatl, just like other Aztec gods, demanded human sacrifice during her ceremonies to sustain her interest in favor of the people. Every night, unmarried girls, wearing their hair long and loose, representing their unmarried status, carried young green corn in offering to the goddess in a procession to her temple. A slave girl was picked to represent the goddess herself and dressed up in a fashion to resemble her and on the last night she was sacrificed in a ceremony for Xilonen.

Download the full edition or view it online

—

Kirby was born in a little burg just south of El Paso, Texas called Fabens. As he understand it, they we were passing through. His history reads like a road atlas. By the time he started school, he had lived in five places in two states. By the time he started high school, that list went to five states, four countries on three continents. Then he joined the Air Force after high school and one year of college and spent 23 years stationed in eleven or twelve places and traveled all over the place doing administrative, security, and electronic things. His final stay was being in charge of Air Force Recruiting in San Diego, Imperial, and Yuma counties. Upon retirement he went back to New England as a Quality Assurance Manager in electronics manufacturing before he was moved to Production Manager for the company’s Mexico operations. He moved to the Phoenix area and finally got his education and ended up teaching. He parted with the university and moved to Whidbey Island, Washington where he was introduced to Manzanillo, Mexico. It was there that he started to publish his monthly article for the Manzanillo Sun. He currently reside in Coupeville, WA, Edmonton, AB, and Manzanillo, Colima, Mexico, depending on whose having what medical problems and the time of year. His time is spent dieting, writing his second book, various articles and short stories, and sightseeing Canada, although that seems to be limited in the winter up there.