By Dan and Lisa Goy from the October 2017 Edition

January 30, 31 and February 1, 2016 (Days 24, 25, 26)

Following our boat tour in Celestún, we headed out before 10 am, off to Chichén Itzá ruins and the village of Pisté. Our route included a backtrack to Mérida and onto the Anillo Periférico around the city and exited at Hwy 180 to Pisté. This was an easy drive and short, the best kind, only 212 km (132 miles) that took less than 3 hours.

Our destination was the “Pirámide Inn” owned by an American who has resided in Mexico for decades. This was basically Dry Camping on a patch of flat grass in front of the hotel. Our 250 pesos ($13 USD) fee included a room (hot showers), access to some limited power, wifi which was good at the office, access to a large pool, a nice patio behind the hotel, a short drive to the Archeological Site, an easy walk to amenities in town and couple of good restaurants and shops within 2 blocks of our RVs. After settling in, we checked out the village and planned our visit to the famous archeological site the next day.

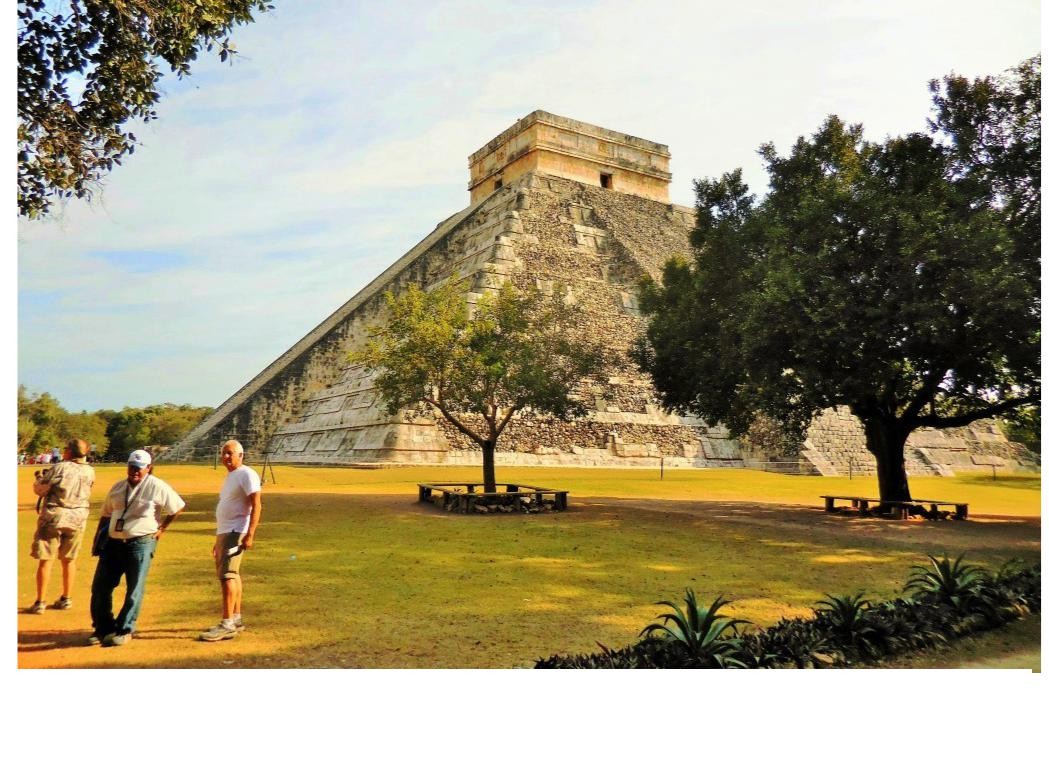

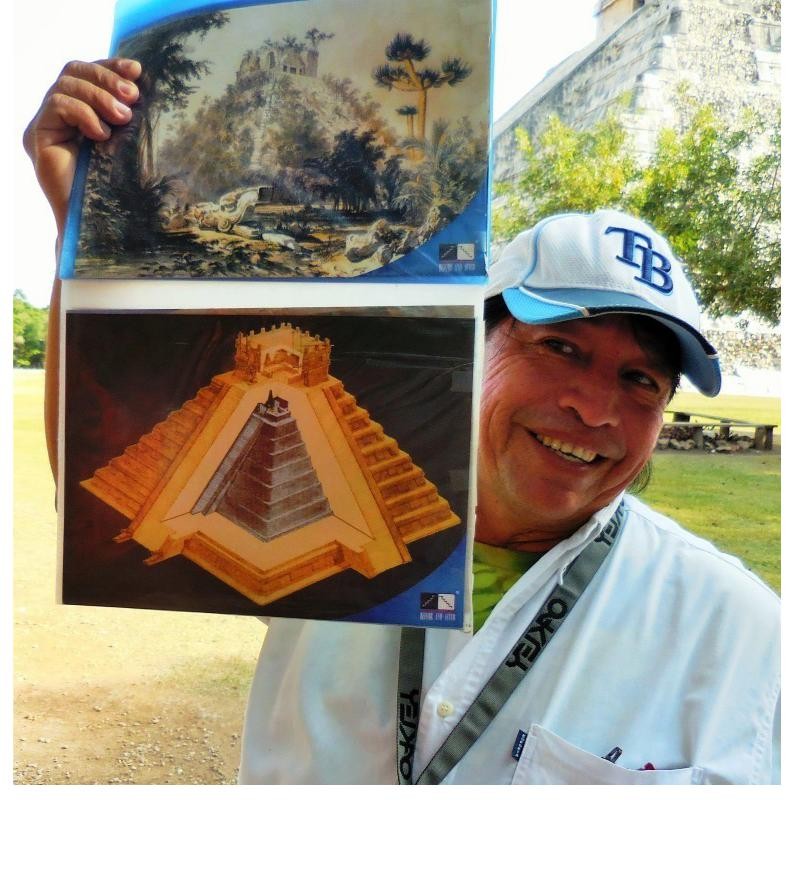

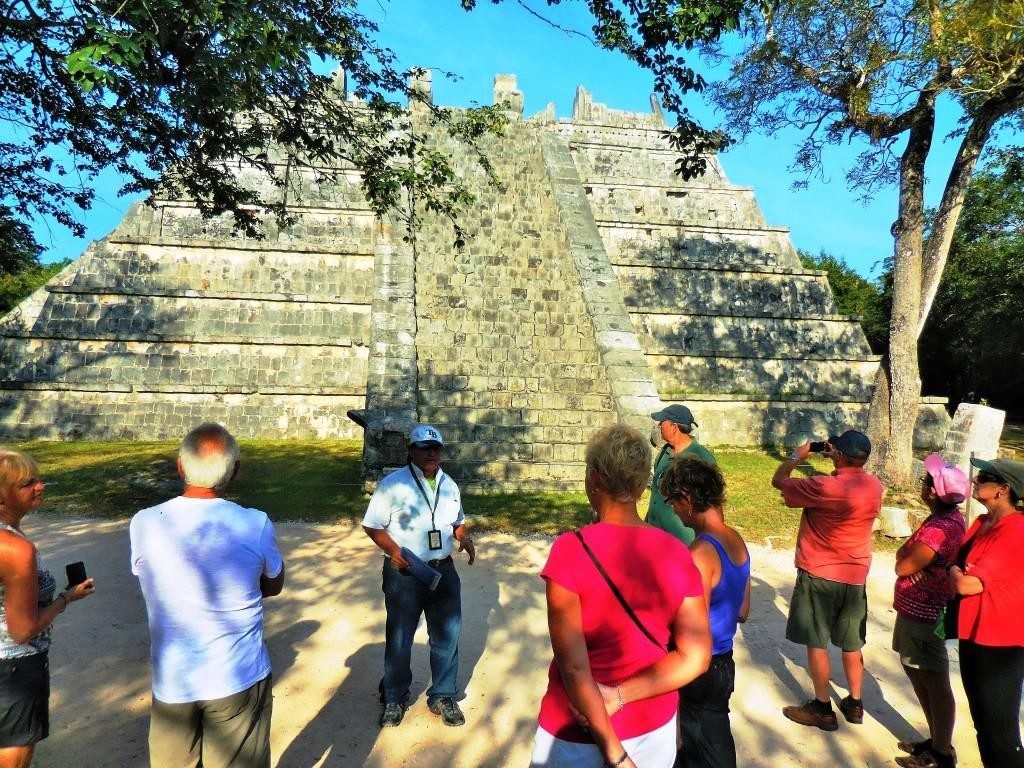

Day 2 in Pisté and we headed out for a tour of the Chichén Itzá ruin that included hiring a guide, Ray. These are amazing ruins which have been restored over the past 200 years. Our guide, Ray, was very knowledgeable about the archeological site and Mayan culture and spoke excellent English. The personal tour took less than 3 hours and we spent another hour or so poking around the site. The exception, of course, was Bruce who caught up with the gang back at the RVs later. The afternoon saw some quality pool time and in the evening the boys headed out to the light show and gals went out for dinner. After the Uxmal light show experience, we were uncertain about what the experience would be at Chichén Itzá.

Although the light show was free, we had no tickets, which seemed very elusive. However, I was able to rely on my experience as Political Staffer in a former life to finesse our way in with the INAH Site Administrator who was very happy to accommodate our group. This was a fabulous laser light show, very similar to what we experienced in Campeche. Victoria and Vancouver would be well served to host such a summer event for free as an attraction for tourists. Afterwards, we went for a bite to eat and met the gals heading back to the RVs. This was

lots of fun and a Sunday night to remember. The next day was February 1st, Constitution Day in Mexico. Many just walked into town, hung out at pool, and later went out for BBQ Chicken with the gang and shopping.

We enjoyed our stop here, certainly a big draw with tourists from Cancun, Playa del Carmen and the Mayan Rivera.

About Chichén Itzá

Chichén Itzá (Spanish: Chichén Itzá – Yucatec Maya: Chi’ch’èen Ìitsha’) was a large pre-Columbian city built by the Maya peo-ple of the Terminal Classic period (c. AD 800–900). Chichén Itzá was one of the largest Maya cities and it was likely to have been one of the mythical great cities, or Tollans, referred to in later Mesoamerican literature. The city may have had the most diverse population in the Maya world, a factor that could have contributed to the variety of architectural styles at the site.

The Maya name “Chichén Itzá” means “At the mouth of the well of the Itzá.” This derives from chi’, meaning “mouth” or “edge,” and ch’en or ch’e’en, meaning “well.” Itzá is the name of an ethnic-lineage group that gained political and economic

dominance of the northern peninsula. One possible translation for Itzá is “enchanter (or enchantment) of the water,” from its, “sorcerer,” and ha, “water.” The name is spelled Chichén Itzá in Spanish, and the accents are sometimes maintained in other languages to show that both parts of the name are stressed on their final syllable.

Chichén Itzá Rules

Chichén Itzá rose to regional prominence towards the end of the Early Classic period (roughly 600 AD). It was, however, to-wards the end of the Late Classic and into the early part of the Terminal Classic that the site became a major regional capital, centralizing and dominating political, sociocultural, economic and ideological life in the northern Maya lowlands. The ascen-sion of Chichén Itzá roughly correlates with the decline and fragmentation of the major centers of the southern Maya low-lands. As Chichén Itzá rose to prominence, the cities of Yaxuna (to the south) and Coba (to the east) were suffering decline. These two cities had been mutual allies, with Yaxuna dependent upon Cobá. At some point in the 10th century Cobá lost a significant portion of its territory, isolating Yaxuna, and Chichén Itzá may have directly contributed to the collapse of both cities.

Chichén Itzá Conquered

According to Maya chronicles, Hunac Ceel, ruler of Mayapan, conquered Chichén Itzá in the 13th century. Hunac Ceel supposedly prophesied his own rise to power. According to custom at the time, individuals thrown into the Cenote Sagrado were believed to have the power of prophecy if they survived. During one such ceremony, the chronicles state, there were no survivors, so Hunac Ceel leaped into the Cenote Sagrado, and when removed, prophesied his own ascension.

While there is some archaeological evidence that indicates Chichén Itzá was at one time looted and sacked, there appears to be greater evidence that it could not have been by Maya-pan, at least not when Chichén Itzá was an active urban center. Archaeological data now indicates that Chichén Itzá declined as a regional center by 1250 CE, before the rise of Mayapan. On-going research at the site of Mayapan may help resolve this chronological conundrum.

While Chichén Itzá “collapsed” or fell (meaning elite activities ceased) it may not have been abandoned. When the Spanish arrived, they found a thriving local population, although it is not clear from Spanish sources if Maya were living in Chichén Itzá or nearby. The relatively high density of population in the region was one of the factors behind the conquistadors’ decision to locate a capital there. According to post-Conquest sources, both Spanish and Maya, the Cenote Sagrado remained a place of pilgrimage.

Spanish conquest

In 1526 Spanish Conquistador Francisco de Montejo (a vet-eran of the Grijalva and Cortés expeditions) successfully pe-titioned the King of Spain for a charter to conquer Yucatán.

His first campaign in 1527, which covered much of the Yucatán peninsula, decimated his forces but ended with the establishment of a small fort at Xaman Ha’, south of what is today Cancún. Montejo returned to Yucatán in 1531 with reinforcements and established his main base at Campeche on the west coast. He sent his son, Francisco Montejo the Younger, in late 1532, to conquer the interior of the Yucatán Peninsula from the north. The objective from the beginning was to go to Chichén Itzá and establish a capital.

Montejo Jr. eventually arrived at Chichén Itzá, which he re-named Ciudad Real. At first he encountered no resistance, and set about dividing the lands around the city and awarding them to his soldiers. The Maya became more hostile over time, and eventually they laid siege to the Spanish, cutting off their supply line to the coast, and forcing them to barricade them-selves among the ruins of the ancient city. Months passed, but no reinforcements arrived. Montejo Jr. attempted an all-out assault against the Maya and lost 150 of his remaining troops. He was forced to abandon Chichén Itzá in 1534 under cover of darkness. By 1535, all Spanish had been driven from the Yu-catán Peninsula. Montejo eventually returned to Yucatán and, by recruiting Maya from Campeche and Champotón, built a large Indio-Spanish army and conquered the peninsula. The Spanish crown later issued a land grant that included Chichén Itzá and by 1588 it was a working cattle ranch.

Modern History

Chichén Itzá entered the popular imagination in 1843 with the book Incidents of Travel in Yucatán by John Lloyd Stephens (with illustrations by Frederick Catherwood). The book recounted Stephens’ visit to Yucatán and his tour of Maya cities, including Chichén Itzá. The book prompted other explorations of the city. In 1860, Desire Charnay surveyed Chichén Itzá and took numerous photographs that he published in Cités et ruines américaines (1863).

In 1875, Augustus Le Plongeon and his wife Alice Dixon Le Plongeon visited Chichén, and excavated a statue of a figure on its back, knees drawn up, and upper torso raised on its elbows with a plate on its stomach. Augustus Le Plongeon called it “Chaacmol” (later renamed “Chac Mool”, which has been the term to describe all types of this statuary found in Meso-america). Teobert Maler and Alfred Maudslay explored Chichén in the 1880s and both spent several weeks at the site and took extensive photographs. Maudslay published the first long-form description of Chichén Itzá in his book, Biologia Centrali-Americana.

In 1894, the United States Consul to Yucatán, Edward Her-bert Thompson purchased the Hacienda Chichén, which in-cluded the ruins of Chichén Itzá. For 30 years, Thompson ex-plored the ancient city. His discoveries included the earliest dated carving upon a lintel in the Temple of the Initial Series and the excavation of several graves in the Osario (High Priest’s Temple). Thompson is most famous for dredging the Cenote Sagrado (Sacred Cenote) from 1904 to 1910, where he recov-ered artifacts of gold, copper and carved jade, as well as the first-ever examples of what were believed to be pre-Columbian Maya cloth and wooden weapons. Thompson shipped the bulk of the artifacts to the Peabody Museum at Harvard University.

In 1913, the Carnegie Institution accepted the proposal of archaeologist Sylvanus G. Morley and committed to conduct long-term archaeological research at Chichén Itzá. The Mexi-can Revolution and the following government instability, as well as World War I, delayed the project by a decade. In 1923, the Mexican government awarded the Carnegie Institution a 10-year permit (later extended another 10 years) to allow U.S. archaeologists to conduct extensive excavation and restoration of Chichén Itzá. Carnegie researchers excavated and restored the Temple of Warriors and the Caracol, among other major buildings. At the same time, the Mexican government excavated and restored El Castillo and the Great Ball Court.

In 1926, the Mexican government charged Edward Thomp-son with theft, claiming he stole the artifacts from the Cenote Sagrado and smuggled them out of the country. The government seized the Hacienda Chichén. Thompson, who was in the United States at the time, never returned to Yucatán. He wrote about his research and investigations of the Maya culture in a book People of the Serpent published in 1932. He died in New Jersey in 1935. In 1944, the Mexican Supreme Court ruled that Thompson had broken no laws and returned Chichén Itzá to his heirs. The Thompsons sold the hacienda to tourism pioneer Fernando Barbachano Peon.

There have been two later expeditions to recover artifacts from the Cenote Sagrado, in 1961 and 1967. The first was sponsored by National Geographic, and the second by private interests. Both projects were supervised by Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH). INAH has conducted an on-going effort to excavate and restore other monuments in the archaeological zone, including the Osario, Akab D’zib, and several buildings in Chichén Viejo (Old Chichén).

Since 2009, Yucatec archaeologists began excavations adjacent to El Castillo under the direction of Rafael (Rach) Cobos. This investigation of the construction, that predates El Castillo, continues today.

Site Layout

Chichén Itzá was one of the largest Maya cities, with the relatively densely clustered architecture of the site core cov-ering an area of at least 5 square kilometres (1.9 sq mi).

Smaller-scale residential architecture extends for an unknown distance beyond this. The city was built upon broken terrain, which was artificially levelled in order to build the major architectural groups, with the greatest effort being expended in the levelling of the areas for the Castillo pyramid, and the Las Monjas, Osario and Main Southwest groups. The site contains many fine stone buildings in various states of preservation, and many have been restored. The buildings were connected by a dense network of paved causeways, called sacbeob. Archaeologists have identified over 80 sacbeob crisscrossing the site, and ex-tending in all directions from the city.

The architecture encompasses a number of styles, including the Puuc and Chenes styles of the northern Yucatán Peninsula. The buildings of Chichén Itzá are grouped in a series of architec-tonic sets, and each set was at one time separated from the other by a series of low walls. The three best-known of these complexes are the Great North Platform, which includes the monuments of El Castillo, Temple of Warriors and the Great Ball Court; The Osario Group, which includes the pyramid of the same name as well as the Temple of Xtoloc; and the Central Group, which includes the Caracol, Las Monjas, and Akab Dzib.

South of Las Monjas, in an area known as Chichén Viejo (Old Chichén) and only open to archaeologists, are several other complexes, such as the Group of the Initial Series, Group of the Lintels, and Group of the Old Castle.

Prominent Structures at Chichén Itzá

Great Ball Court

Archaeologists have identified thirteen ballcourts for playing the Mesoamerican ballgame in Chichén Itzá, but the Great Ball Court about 150 metres (490 ft) to the north-west of the Castillo is by far the most impressive. It is the largest and best preserved ball court in ancient Mesoamerica. It measures 168 by 70 metres (551 by 230 ft). The parallel platforms flanking the main playing area are each 95 metres (312 ft) long. The walls of these platforms stand 8 metres (26 ft) high; set high up in the centre of each of these walls are rings carved with intertwined feathered serpents. At the base of the high interior walls are slanted benches with sculpted panels of teams of ball players. In one panel, one of the players has been decapitated; the wound emits streams of blood in the form of wriggling snakes.

At one end of the Great Ball Court is the North Temple, also known as the Temple of the Bearded Man (Templo del Hombre Barbado). This small masonry building has detailed bas relief carving on the inner walls, including a center figure that has carving under his chin that resembles facial hair. At the south end is another, much bigger temple, but in ruins. Built into the east wall are the Temples of the Jaguar.

The Upper Temple of the Jaguar overlooks the ball court and has an entrance guarded by two, large columns carved in the familiar feathered serpent motif. Inside there is a large mural,

much destroyed, which depicts a battle scene. In the entrance to the Lower Temple of the Jaguar, which opens behind the ball court, is another Jaguar throne, similar to the one in the inner temple of El Castillo, except that it is well worn and missing paint or other decoration. The outer columns and the walls inside the temple are covered with elaborate bas-relief carvings.

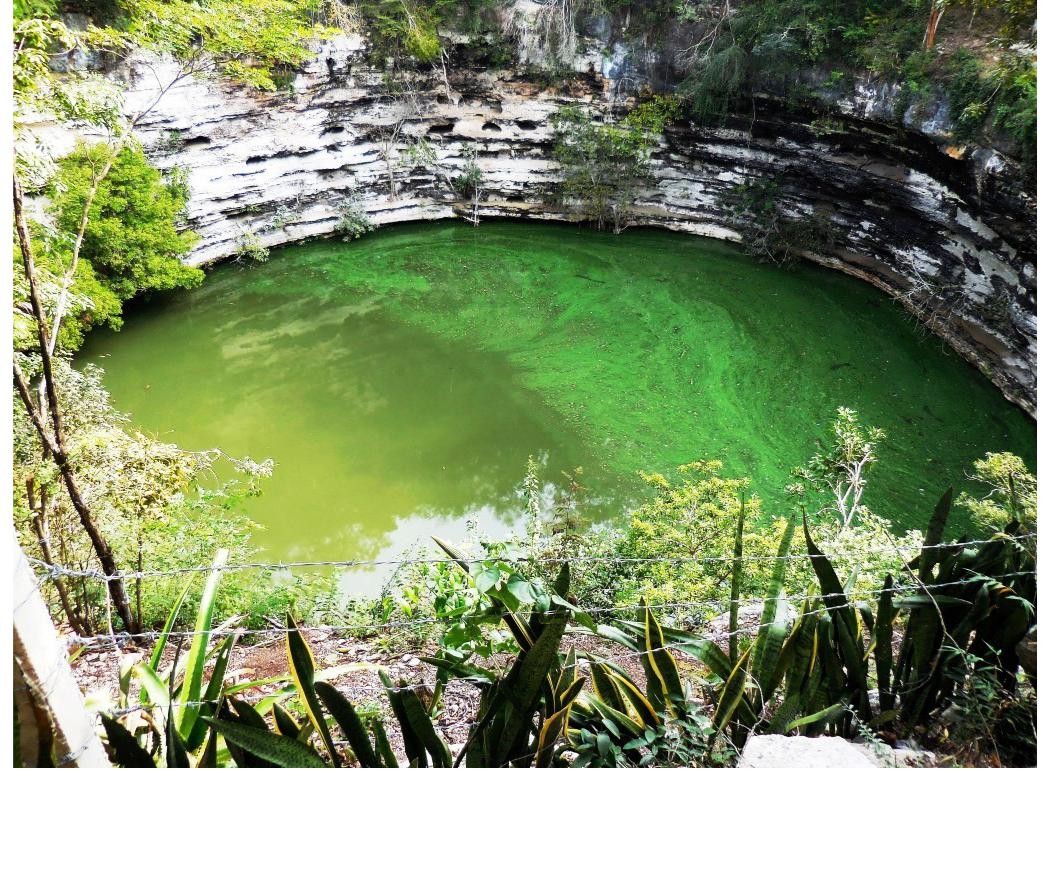

Cenote Sagrado

The Yucatán Peninsula is a limestone plain, with no rivers or streams. The region is pockmarked with natural sinkholes, called cenotes, which expose the water table to the surface. One of the most impressive of these is the Cenote Sagrado, which is 60 metres (200 ft) in diameter, and sheer cliffs that drop to the water table some 27 metres (89 ft) below. The Cenote Sagrado was a place of pilgrimage for ancient Maya people who, according to ethnohistoric sources, would conduct sacrifices during times of drought. Archaeological investigations support this as thousands of objects have been removed from the bottom of the cenote, including material such as gold, carved jade, copal, pottery, flint, obsidian, shell, wood, rubber, cloth, as well as skeletons of children and men.

Temple of the Warriors

The Temple of the Warriors complex consists of a large stepped pyramid fronted and flanked by rows of carved columns depicting warriors.This complex is analogous to Temple B at the Toltec capital of Tula, and indicates some form of cultural contact between the two regions. The one at Chichén Itzá.however, was constructed on a larger scale. At the top of the stairway on the pyramid’s summit (and leading towards the entrance of the pyramid’s temple) is a Chac Mool. This temple encases or entombs a former structure called The Temple of

the Chac Mool. The archeological expedition and restoration of this building was done by the Carnegie Institution of Washing-ton from 1925 to 1928. A key member of this restoration was Earl H. Morris who published the work from this expedition in two volumes entitled Temple of the Warriors.

Group of a Thousand Columns

Along the south wall of the Temple of Warriors are a series of what are today exposed columns although, when the city was inhabited, these would have supported an extensive roof system. The columns are in three distinct sections: a west group, that extends the lines of the front of the Temple of Warriors; a north group, which runs along the south wall of the Temple of Warriors and contains pillars with carvings of soldiers in basrelief; and a northeast group, which apparently formed a small temple at the southeast corner of the Temple of Warriors, which contains a rectangular decorated with carvings of people or gods, as well as animals and serpents. The northeast column temple also covers a small marvel of engineering, a channel that funnels all the rainwater from the complex some 40 metres (130 ft) away to a rejollada, a former cenote.

To the south of the Group of a Thousand Columns is a group of three, smaller, interconnected buildings. The Temple of the Carved Columns is a small elegant building that consists of a front gallery with an inner corridor that leads to an altar with a Chac Mool. There are also numerous columns with rich, bas-relief carvings of some 40 personages. A section of the upper façade with a motif of x’s and o’s is displayed in front of the

structure. The Temple of the Small Tables is an unrestored mound. And the Thompson’s Temple (referred to in some sources as Palace of Ahau Balam Kauil) is a small building with two levels that has friezes depicting Jaguars (balam in Maya) as well as glyphs of the Maya god Kahuil.

“El Caracol” – The Observatory

El Caracol (“The Snail”) is located to the north of Las Monjas. The structure is dated to around AD 906, the Late Classic pe-riod of Mesoamerican chronology, by the stele on the Upper Platform. It is suggested that the El Caracol was an ancient Mayan observatory building and provided a way for the Mayan people to observe changes in the sky due to the flattened landscape of the Yucatán with no natural markers for this func-tion around Chichén Itzá. The observers could view the sky above the vegetation on the Yucatán Peninsula without any ob-struction. It is a round building on a large square platform. It gets its name from the stone spiral staircase inside. The structure, with its unusual placement on the platform and its round shape (the others are rectangular, in keeping with Maya prac-tice), is theorized to have been a protoobservatory with doors and windows aligned to astronomical events, specifically around the path of Venus as it traverses the heavens.

Mayan astronomers knew, from naked-eye observations, that Venus appeared on the western and disappeared on the eastern horizons at different times in the year, and that it took 584 days to complete one cycle. They also knew that five of these Venus cycles equaled eight solar years. Venus would therefore make an appearance at the northerly and southerly extremes at eight-year intervals. Of 29 possible astronomical events (eclipses, equinoxes, solstices, etc.) believed to be of interest to the Mesoamerican residents of Chichén Itzá, sight lines for 20 can be found in the structure. Since a portion of the tower rest-ing on El Caracol has been lost, it is possible that other observations will never be ascertained.

Tourism

Tourism has been a factor at Chichén Itzá for more than a

century. John Lloyd Stephens, who popularized the Maya Yucatán in the public’s imagination with his book Incidents of Travel in Yucatan, inspired many to make a pilgrimage to Chichén Itzá. Even before the book was published, Benjamin Norman and Baron Emanuel von Friedrichsthal traveled to Chichén after meeting Stephens, and both published the results of what they found. Friedrichsthal was the first to photograph Chichén Itzá, using the recently invented daguerreotype.

After Edward Thompson in 1894 purchased the Hacienda Chichén, which included Chichén Itzá, he received a constant stream of visitors. In 1910, he announced his intention to construct a hotel on his property, but abandoned those plans, probably because of the Mexican Revolution.

In the early 1920s, a group of Yucatecans, led by writer/ photographer Francisco Gómez Rul, began working toward expanding tourism to Yucatán. They urged Governor Felipe Carrillo Puerto to build roads to the more famous monuments, including Chichén Itzá. In 1923, Governor Carrillo Puerto officially opened the highway to Chichén Itzá. Gómez Rul published one of the first guidebooks to Yucatán and the ruins.

Gómez Rul’s son-in-law, Fernando Barbachano Peon (a grand-nephew of former Yucatán Governor Miguel Barbachano), started Yucatán’s first official tourism business in the early 1920s. He began by meeting passengers who arrived by steam-ship at Progreso, the port north of Mérida, and persuading them to spend a week in Yucatán, after which they would catch the next steamship to their next destination. In his first year, Barbachano Peon reportedly was only able to convince seven passengers to leave the ship and join him on a tour. In the mid -1920s Barbachano Peon persuaded Edward Thompson to sell 5 acres (20,000 m2) next to Chichén for a hotel. In 1930, the Ma-yaland Hotel opened, just north of the Hacienda Chichén, which had been taken over by the Carnegie Institution.

In 1944, Barbachano Peon purchased all of the Hacienda Chichén, including Chichén Itzá, from the heirs of Edward Thompson. Around that same time the Carnegie Institution completed its work at Chichén Itzá and abandoned the Haci-enda Chichén, which Barbachano turned into another seasonal hotel.

In 1972, Mexico enacted the Ley Federal Sobre Monumentos y Zonas Arqueológicas, Artísticas e Históricas (Federal Law over Monuments and Archeological, Artistic and Historic Sites) that put all the nation’s pre-Columbian monuments, including those at Chichén Itzá, under federal ownership. There were now hun-dreds, if not thousands, of visitors every year to Chichén Itzá, and more were expected with the development of the Cancún resort area to the east.

In the 1980s, Chichén Itzá began to receive an influx of visi-tors on the day of the spring equinox. Today several thou-sand show up to see the light-and-shadow effect on the Tem-

ple of Kukulcán in which the feathered serpent god appears be seen to crawl down the side of the pyramid. Tourists are also amazed by the acoustics at Chichén Itzá. For instance a hand-clap in front of the staircase of the El Castillo pyramid is fol-lowed by an echo that resembles the chirp of a quetzal as in-vestigated by Declercq.

Chichén Itzá, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is the second-most visited of Mexico’s archaeological sites. The archaeo-logical site continues to draw visitors from several popular tourist resorts and Mérida, who make a day trip on tour buses.

Over the past several years, INAH, which manages the site, has been closing monuments to public access. While visitors can walk around them, they can no longer climb them or go inside their chambers. The most recent was El Castillo, which was closed after a San Diego, California, woman fell to her death in 2006.

Chichén Itzá was one of the most-visited archaeological sites in Mexico; in 2007 it was estimated to receive an average of 1.2 million visitors every year and Chichén Itzá’s El Castillo was named one of the New Seven Wonders of the World after a worldwide vote. Despite the fact that the vote was sponsored by a commercial enterprise, and that its methodology was criti-cized, the vote was embraced by government and tourism offi-cials in Mexico who projected that, as a result of the publicity, the number of tourists expected to visit Chichén Itzá would double by 2012.

We can say without question that Chichén Itzá continues to be a huge draw with tourists given the buses and visitors we ex-perienced during our visit in 2016.

Submitted by Dan and Lisa Goy

Owners of Baja Amigos RV Caravan Tours

Experiences from our 90-day Mexico RV Tour: January 7-April 5, 2016 www.BajaAmigos.net

Chichén Itzá

Download the full edition or view it online

Dan and Lisa Goy, owners of Baja Amigos RV Caravan Tours, have been making Mexico their second home for more than 30 years and love to introduce Mexico to newcomers.