By Kirby Vickery on the December 2020 Edition

If you get into Mesoamerican history, you’ll find a time rich in folklore and sociological color. You will also find lots of warring, fighting, sacrifice, both animal and human, and a continuation of mythological beliefs that carry from one dominant society to the next.

There is an area just north and west of today’s Mexico City that hosts the remains of the Chichimec tribes. They were a semi nomadic people who didn’t wear much (according to some sites on the internet) and were warlike. Their diet would have been very similar to what you and I can find as Mexican Street Food or served along the Jardín de Salagua in Manzanillo on weekends today.

They grew to power in the 12 and 13th century C.E. and were mostly known for assisting in tearing down the Mayan empire only to lose it to the Toltecs at about the same time. As with the Olmecs, there isn’t that much data on them, primarily because the Aztecs who came to be in power after about four hundred years were a little more warlike and savage than the Chichimec and the Toltec. They destroyed what would thrill archeologists today.

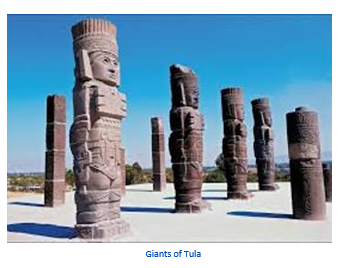

We do know a great deal about the Toltec, though, because they were in power and were growing throughout Mexico and the northern parts of Central America during their four-hundred year stand. [I found it odd that several web sites have the Chichimec ending the Toltec hegemony when it was the other way around.]

The Toltec way of life was similar to the rest of the Mesoamerican world. It was family-based, with a father as head of the household. Most male children were removed from the house-hold at around ten years old or so. They went for training in the military as warriors or into the priesthood. Some of the girl children were treated in a similar manner. Most of the girls stayed with the family until they moved out to support their own families.

The Toltec way of life was similar to the rest of the Mesoamerican world. It was family-based, with a father as head of the household. Most male children were removed from the house-hold at around ten years old or so. They went for training in the military as warriors or into the priesthood. Some of the girl children were treated in a similar manner. Most of the girls stayed with the family until they moved out to support their own families.

It is believed that there was a strong middle class of artisans, farmers and craftsmen, with the military riding high in the social world. The highest of the high was the priesthood, while the women cooked, cleaned house, and kept everybody in good clothing. Like the Maya, the Toltec were thought to have an extensive trade system made up from the places they fought and won, rather than making slaves out of everyone.

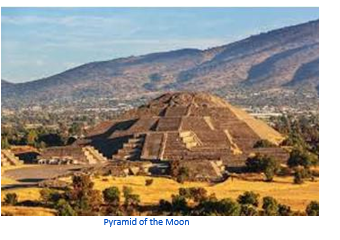

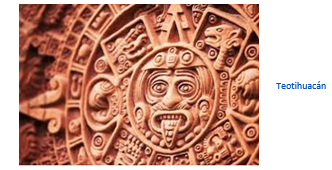

The main city of the Toltec was Teotihuacán. It rose as a new religious center in the Mexican highland around the lifetime of

Christ (roughly 30 AD), about 25 miles north and east of the present day city of Mexico City. The city grew and became one of the largest and most populated cities in the new world.

By the fourth century, the influence of Teotihuachán was felt throughout most parts of Mesoamerica, as it was a place of religion, culture and art. The city was the sixth largest city in the world during its zenith, having an estimated population of 200,000 people.

The city functioned for centuries. It grew and developed as a place of influence until its unexpected and mysterious collapse in the seventh century AD. If you haven’t been to see it, yet you should make plans and go.

The centrally located ‘Avenue of the Dead’ is the main street in the city. It divided the city in half. The road is about two and a half kilometers long. At the north end, there is the Pyramid of the Moon. This complex was constructed as the main monument for the Plaza of the Moon. The structure faces south to-wards the Rio San Juan.

On the eastern side of the Avenue of the Dead, but in the center of the city, there is the larger Pyramid of the Sun. A cave is located under the pyramid. Some scholars believe the cave was used for ritual activities, probably surrounding religion. The pyramid consisted of four steep platforms and a temple. Little is known about the temple itself, though, as the upper part of the pyramid has been destroyed. The Feathered Serpent Pyramid was dedicated to Quetzlcoatl and was built in the Ciudadela or ‘Citadel’.

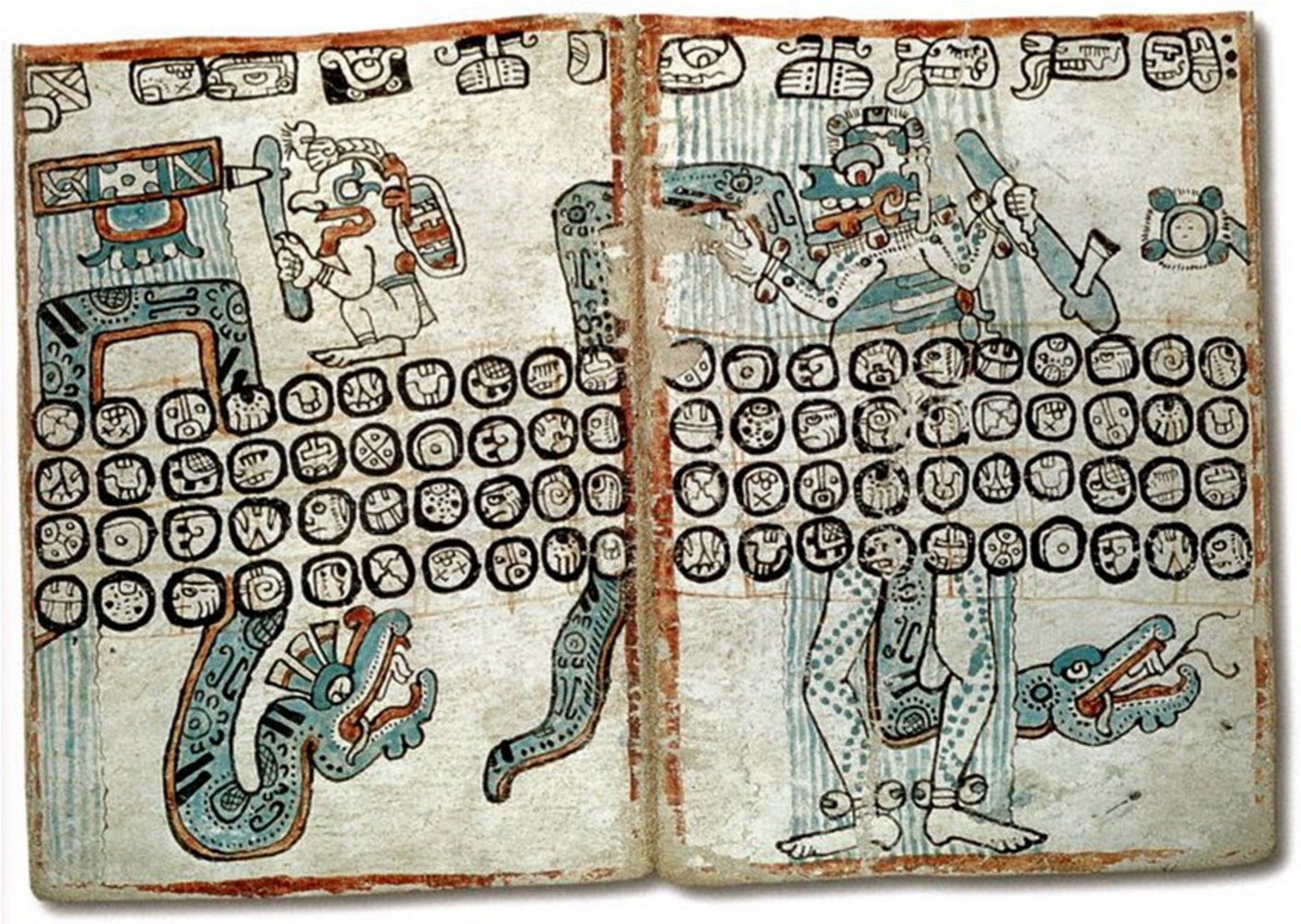

The Toltec religion was focused around two major gods. The first was Quetzlcoatl, the plumed serpent god. The Aztecs put an ‘a’ in the word after the ‘z’. Quetzalcoatl represented many ideas, including, but not limited to, learning, fertility, holiness, gentility, culture, philosophy, as well as good. Quetzalcoatl means “Precious serpent” or “Quetzal-feathered Serpent”. In the 17th century, Ixtlilxóchitl, a surviving descendant of Aztec royalty, wrote, “Quetzalcoatl, in its literal sense, means ‘serpent of precious feathers’, but in the allegorical sense, ‘wisest of men’.” The second god in the religion was Tezcatlipoca, the smoked mirror. Texcatlipoca was the opposite of Quetzalcoatl, as he represented war, tyranny, and evil.

Tezcatlipoca became the central deity in Aztec religion and his main festival was the Toxcatl ceremony celebrated in the month of May. One of the four sons of Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl, he is associated with a wide range of concepts, including the night sky, the night winds, hurricanes, the north, the earth, obsidian, enmity, discord, rulership, divination, temptation, jaguars, sorcery, beauty, war and strife.

His name in the Nahuatl language is often translated as “Smoking Mirror” and alludes to his connection to obsidian, the material from which mirrors were made in Mesoamerica and which were used for shamanic rituals and prophecy.

His name in the Nahuatl language is often translated as “Smoking Mirror” and alludes to his connection to obsidian, the material from which mirrors were made in Mesoamerica and which were used for shamanic rituals and prophecy.

In addition to Quetzalcoatl and Tezactlipoca, the Toltecs had many other gods, though little is known of what their names were and what they represented. Their religion thus was polytheistic. It is possible that some of their gods were later adopted by the Aztecs, though this is only speculation. Their religion focused on human sacrifice to appease the gods.

Human sacrifice was a very painful process for the person being sacrificed, as their heart would be cut out of their body while it still was beating. In addition to sacrifice, the religion included a game called Tlatchli or “The Game.”

The game was very popular with other cultures such as the Ma-ya and the Aztec. Think of the glory of having the entire losing team being sacrificed to the Feathered Dragon.

The Toltec people left no evidence of their creation myths or of their belief of life after death. There is little evidence, although some speculate that the Toltec peoples’ idea of death was freedom from this world.

The Toltec people left no evidence of their creation myths or of their belief of life after death. There is little evidence, although some speculate that the Toltec peoples’ idea of death was freedom from this world.

One idea was that man became a god upon death. Another thought regarding their beliefs was a unification of souls after death. Toward this end, they didn’t focus on the afterlife in life because all souls went together. My thought is that because they practiced human sacrifice as a gift to the gods which would mean a higher level of afterlife for those sacrificed.

If that were true, then there was a hierarchy in death so what the Aztecs and the Maya practiced also held for the Toltec. Carrying this thought one step further, the Toltec mythology was just transferred to and called Aztec Mythology by Aztecs.

If that were true, then there was a hierarchy in death so what the Aztecs and the Maya practiced also held for the Toltec. Carrying this thought one step further, the Toltec mythology was just transferred to and called Aztec Mythology by Aztecs.

They copied most everything else from their predecessors. This means that should you want to read any Toltec mythology then you can turn your book to the Aztec pages.

—

Kirby was born in a little burg just south of El Paso, Texas called Fabens. As he understand it, they we were passing through. His history reads like a road atlas. By the time he started school, he had lived in five places in two states. By the time he started high school, that list went to five states, four countries on three continents. Then he joined the Air Force after high school and one year of college and spent 23 years stationed in eleven or twelve places and traveled all over the place doing administrative, security, and electronic things. His final stay was being in charge of Air Force Recruiting in San Diego, Imperial, and Yuma counties. Upon retirement he went back to New England as a Quality Assurance Manager in electronics manufacturing before he was moved to Production Manager for the company’s Mexico operations. He moved to the Phoenix area and finally got his education and ended up teaching. He parted with the university and moved to Whidbey Island, Washington where he was introduced to Manzanillo, Mexico. It was there that he started to publish his monthly article for the Manzanillo Sun. He currently reside in Coupeville, WA, Edmonton, AB, and Manzanillo, Colima, Mexico, depending on whose having what medical problems and the time of year. His time is spent dieting, writing his second book, various articles and short stories, and sightseeing Canada, although that seems to be limited in the winter up there.