By Dan and Lisa Goy on the December 2020 Edition

Baja Pictographs and Petroglyphs

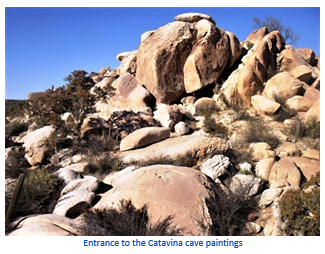

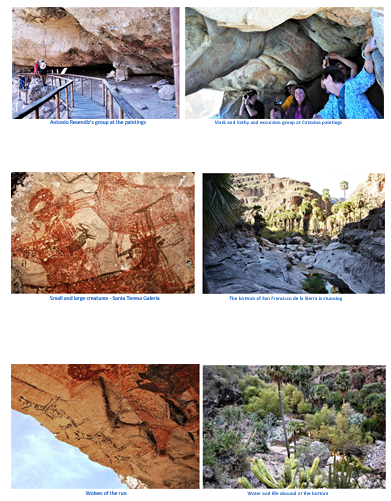

A regular stop on our Baja tours are Cave paintings near Catavina, which are easily accessible, and a short drive from where we camp for our overnight stay. There are over 350 archeological pictographs and petroglyph sites across the Baja peninsula, more than any other location in the Americas. The vast majority of these sites are hidden and thousands of years old. Though Europe has the well known Cave of Altamira in Spain and France’s Lascaux caves and the Chauvet Pont-d’Arc Cave, all of which have more modern prestige, Baja’s cave paintings are both larger and more numerous than those in Europe. However, much like the peninsula itself that went largely unexplored and unsettled until the 19th century, the mural art, hidden away within the peninsula’s sierras, went unrecognized and unstudied, for the most part, until the mid-20th century.

A regular stop on our Baja tours are Cave paintings near Catavina, which are easily accessible, and a short drive from where we camp for our overnight stay. There are over 350 archeological pictographs and petroglyph sites across the Baja peninsula, more than any other location in the Americas. The vast majority of these sites are hidden and thousands of years old. Though Europe has the well known Cave of Altamira in Spain and France’s Lascaux caves and the Chauvet Pont-d’Arc Cave, all of which have more modern prestige, Baja’s cave paintings are both larger and more numerous than those in Europe. However, much like the peninsula itself that went largely unexplored and unsettled until the 19th century, the mural art, hidden away within the peninsula’s sierras, went unrecognized and unstudied, for the most part, until the mid-20th century.

Although the cave paintings did not draw much modern attention until the 20th century, Spanish missionaries knew of the large murals and discussed them in their records.

The first recording of the wall paintings, as yet discovered, can be found in Francisco Javier Clavigero’s Historia de la Antigua Baja California, written in 1789. Clavigero describes the paintings discovered on the rock shelters, found between the San Ignacio Mission and the Mission Santa Gertrudis. Originally, the paintings were thought to be somewhere around 2,000 years old. However, more recent carbon dating tests have suggested that some of the paintings may have been created 7,500 to 10,000 years ago.

Many of these sites were often described as “Great Murals

(Pictographs) and were also noted by Jesuit missionaries José Mariano Rotea and Francisco Escalante in the eighteenth century. The first scientific studies were made between 1889 and 1913 by a French naturalist, Léon Diguet. Mexican journalist

Fernando Jordan and archaeologists Barbro Dahlgren and Javier Romero reported on Great Mural sites in the early 1950s.

The Great Murals came to popular attention in the United States through a 1962 Life magazine article by mystery writer Erle Stanley Gardner. The exploration led to an article in Life and the publication of Gardner’s The Hidden Heart of Mexico. Since then, numerous investigators have documented and analyzed the sites. Garner’s funded exploration led to photographer Harry Crosby’s more involved, mule-mounted exploration led to the publication of The Cave Paintings of Baja Califor-nia: Discovering the Great Murals of an Unknown People.

Another notable individual was Eve Ewing who has been studying the art for 50 years and has made over a hundred trips to view the different paintings. Other notables who have made extensive contributions on this subject are Clement W. Meighan, Campbell Grant, Enrique Hambleton, Justin R. Hyland, and María de la Luz Gutiérrez.

Another notable individual was Eve Ewing who has been studying the art for 50 years and has made over a hundred trips to view the different paintings. Other notables who have made extensive contributions on this subject are Clement W. Meighan, Campbell Grant, Enrique Hambleton, Justin R. Hyland, and María de la Luz Gutiérrez.

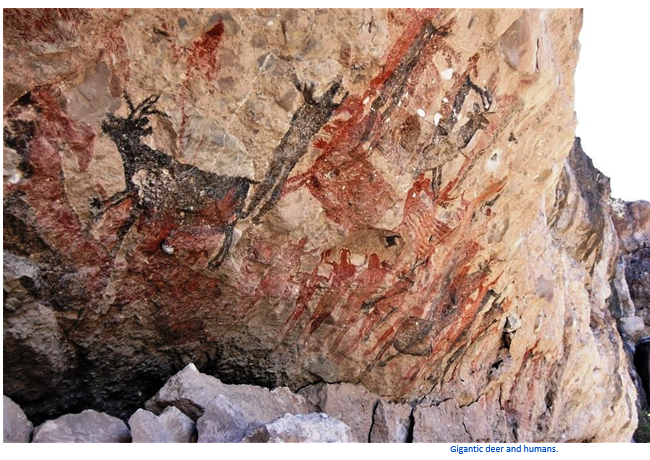

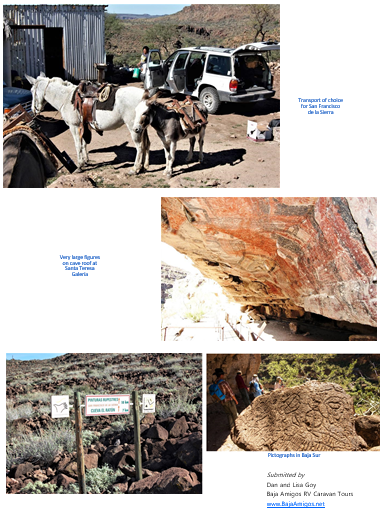

Overall, the art consists of prehistoric paintings of humans and other animals, often larger than life-size, on the walls and ceilings of natural rock shelters in the mountains of northern Baja California Sur and southern Baja California, Mexico. The rock art may be either monochrome or polychrome. Red and black were the colors most frequently used, but white, pink, orange, and green also occur. The most common figures are humans and deer, but a variety of other animals, such as rabbits, big horn sheep, birds, fish, and snakes are also represented. The human images often include stylized headdresses. A minority of human and animal images are overlain with depictions of projectiles.

The images are essentially silhouettes, without representational details inside their outlines. Overpainting of earlier by later images is very common. Some murals seem to show intentional composition in their arrangements of multiple images but, in many cases, the figures seem to have been painted individually, without regard to other nearby (or underlying) images.

The images are essentially silhouettes, without representational details inside their outlines. Overpainting of earlier by later images is very common. Some murals seem to show intentional composition in their arrangements of multiple images but, in many cases, the figures seem to have been painted individually, without regard to other nearby (or underlying) images.

Much like other early cave paintings, their meaning and cultural significance remain ambiguous and involve some conjecture. Many archeologists and anthropologists believe that the Baja rock paintings suggest a culture heavily dependent on hunting, or a mystical hunting magic, as the majority of animals are shown as being struck by arrows.

Similarly, as many human figures were painted over those of animals, scholars suggest that the culture believed in human dominance over the animals. Lastly, the rock paintings’ locations themselves have drawn some interest.

Similarly, as many human figures were painted over those of animals, scholars suggest that the culture believed in human dominance over the animals. Lastly, the rock paintings’ locations themselves have drawn some interest.

Their remote, usually inaccessible, locations indicate that the precise location was closely considered before painting. Further, whereas some paintings were done on walls and ceilings easy to reach, some are located in places that would require scaffolding to reach. Scholars such as Meighan believe that this demonstrates the significance of the location and the act of painting rather than focusing on the painting itself. The prehistoric people responsible for creating the art were most likely ancestors of the Guachimi and Cochimi Indians, the indigenous inhabitants of the area when the Spanish arrived. The motives for the primitive art remain unknown and subject to speculation.

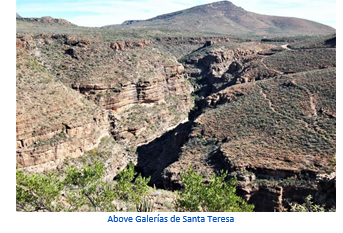

Baja California’s Sierra de San Francisco is nature’s canvas, and the region is the heart of Baja’s prominent archeological sites. This group of monuments are included on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

Baja California’s Sierra de San Francisco is nature’s canvas, and the region is the heart of Baja’s prominent archeological sites. This group of monuments are included on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

Cueva del Ratón (Cave of the Mouse) is more of an overhang than a cave, but the rock mural is located at the highest elevation of any mural within the Sierra de San Francisco as it over-looks Cerro de la Laguna. The mural is about 40 feet long and depicts a human with a black face patch, deer, rabbits, sheep, and a mountain lion. Humans painted with a black face patch can only be found at four other sites in Baja, and the body colored by fine vertical stripes is also a distinguishing feature.

Cueva de la Soledad (Cave of Loneliness) is appropriately named for its remote perch high on the plateau. Cueva de la Soledad is actually one of many cavities on the rock face, but it’s the largest one.

The images are painted on the cavity’s roof, and the mural includes large images of human figures, referred to as “monos,” overlaying images of animals. The cacophony of images may be static, but they suggest a frantic surge of movement through its mayhem. A colored checkerboard, created by yellow-lined boxes filed in alternating red and black, is depicted on an adjacent wall.

Cueva de las Flechas (Cave of the Arrows) is one of Baja’s more renowned caves. This cave received its name from the distinctive use of arrows that are portrayed as being in the hu-man figures rather than the animals.

One figure even has ten arrows within it. While the incorpora-tion of arrows within the rock paintings of Baja are common, they are primarily painted as part of the hunting culture and, as such, are jutting out of animals.

One figure even has ten arrows within it. While the incorpora-tion of arrows within the rock paintings of Baja are common, they are primarily painted as part of the hunting culture and, as such, are jutting out of animals.

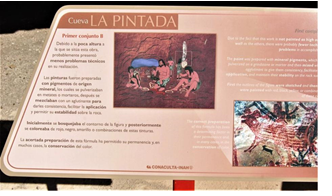

Cueva La Pintada (Painted Cave) remains Baja California’s largest collection of murals as it spans 500 feet across the base of the cavern at its opening. The well-preserved murals lie in the central portion of Arroyo de San Pablo, and many speculate that the rock’s good condition, with little erosion, also helped preserve the paintings.

Cueva Pintada features a variety of wildlife with distinctly homogenously sized figures. The mural portrays images of monos, birds with wings in flight, sheep, deer, and marine life such as whales and sea lions.

The paintings’ immense size have caused many to suggest that the painters fashioned platforms and scaffolds from the neighboring palm groves that enabled them to reach the high surfaces.

Cueva de la Serpiente (Cave of the Serpent) lies within Baja’s central sierras and is known for its depiction of the two distinct deer-headed serpents. The right serpent remains complete to-day, and its ears and antlers follow into a body banded with black lines and culminated into a bifurcated tail. The left snake has not survived the years as well and, while the head remains, the serpent’s body has faded away with fallen rock. The mural itself is rather large at almost eight meters and over fifty animal and human figures appear to frolic along the two serpents’ encompassing bodies. This rock mural is unique in that the animals are fanciful, and scholars have suggested the serpents represent renewal and creation for all creatures rather than a more mundane depiction of life.

Cueva de la Serpiente (Cave of the Serpent) lies within Baja’s central sierras and is known for its depiction of the two distinct deer-headed serpents. The right serpent remains complete to-day, and its ears and antlers follow into a body banded with black lines and culminated into a bifurcated tail. The left snake has not survived the years as well and, while the head remains, the serpent’s body has faded away with fallen rock. The mural itself is rather large at almost eight meters and over fifty animal and human figures appear to frolic along the two serpents’ encompassing bodies. This rock mural is unique in that the animals are fanciful, and scholars have suggested the serpents represent renewal and creation for all creatures rather than a more mundane depiction of life.

Boca de San Julio can be found nearby Cueva Pintada. This cave painting portrays a uniquely dynamic rendition of a leaping buck and a deer linked in motion. Los Músicos also lies in this neighboring cluster of caves. Los Músicos was named for its abstract style that is reminiscent of musical notes. The painting shows humans dancing upon a grid of white lines resembling a score.

Boca de San Julio can be found nearby Cueva Pintada. This cave painting portrays a uniquely dynamic rendition of a leaping buck and a deer linked in motion. Los Músicos also lies in this neighboring cluster of caves. Los Músicos was named for its abstract style that is reminiscent of musical notes. The painting shows humans dancing upon a grid of white lines resembling a score.

With their arms outstretched, the human figures appear to be celebrating in joy. Of course, with abstract art of a lost people such as this, much of the meaning is speculation. Baja’s cave paintings contain a vocabulary of symbols we have yet to fully decipher.

With their arms outstretched, the human figures appear to be celebrating in joy. Of course, with abstract art of a lost people such as this, much of the meaning is speculation. Baja’s cave paintings contain a vocabulary of symbols we have yet to fully decipher.

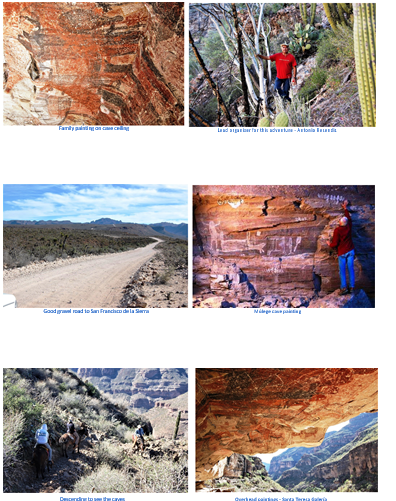

Control of these archeological sites is under the guidance of Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH). All visitors to the cave paintings must purchase a special permit and must be accompanied by a registered guide which are readily available and inexpensive.

We have found, over the years, the best communities to organize and plan excursions to these various archeological sites are Bahía de los Ángeles, Guerrero Negro, Vizcaino, San Ignacio, Múlege and Loreto. For those keen on more adventure, we recommend to add any one of these stops to your travel plans.

|

|

|

|

Dan and Lisa Goy, owners of Baja Amigos RV Caravan Tours, have been making Mexico their second home for more than 30 years and love to introduce Mexico to newcomers.