By David Fitzpatrick from the April 2011 Edition

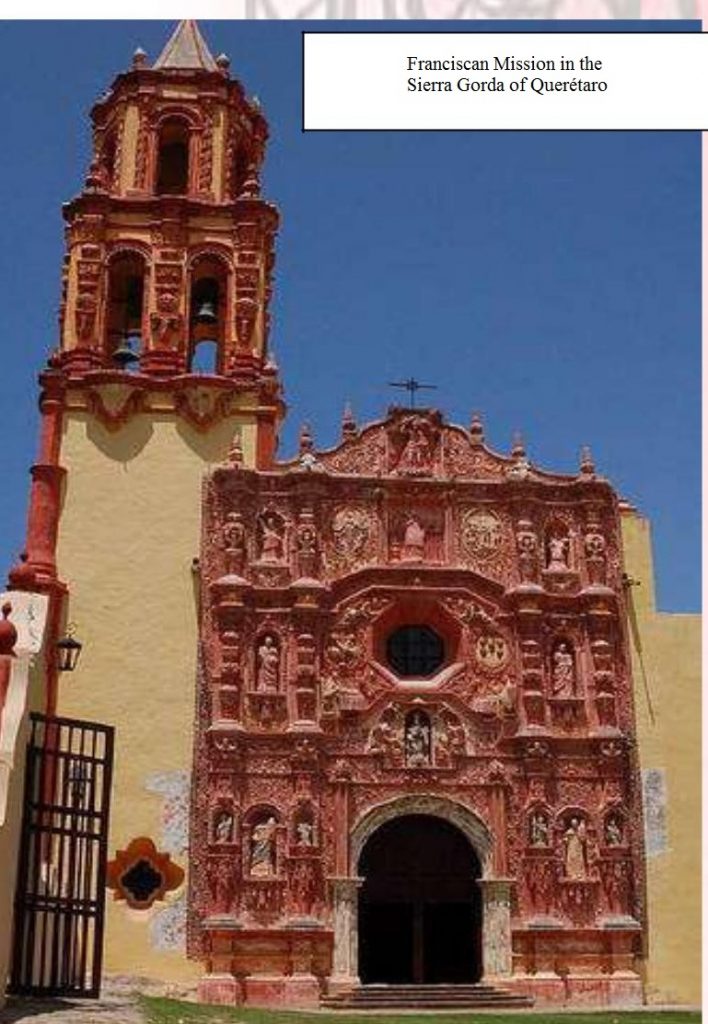

The Catholic Missions in Mexico and other parts of Latin America

The early Spanish colonizers of Latin America considered it important to establish a permanent, functioning, European style community as quickly as possible. Since the introduction of European Spaniards in sufficient numbers seemed difficult, if not impossible, the “civilizing” of the local populations to ready them to take their place in a European society, became high priority

As it happened, this purpose dovetailed neatly with the proselytizing mission of the Roman Catholic Church. The Church considered that it had a God-given mission to spread the word of Christianity throughout all parts of the world. The acquisition by Spain of very large territories where Christianity was unknown, therefore, constituted a clear and unambiguous task.

The State, in cooperation with the Church, set about therefore, to turn the native populations into devout Christians and productive, tax-paying citizens.

All of the major monastic orders played a role, at one time or another, in what was a very major endeavour to convert large portions of the native populations to Christianity. But none equalled the truly heroic efforts of large numbers of Franciscan Friars, many of whom consecrated a major part of their lives to this effort.

The Franciscan Friars were, in general, men of great charitable purpose and felt strong empathy and often affection for the native peoples. But their methods, although in keeping with customs and attitudes of their time, seem Eurocentric, condescending, and even harsh to 21st Century observers.

First of all, they worked on the assumption that the Indians were “heathens”, “pagans”, or “barbarians” needing to be “civilized”. No value whatever was attached to the culture and civilization of the natives, which had, after all, developed over a period of thousands of years.

All traces of the traditional religion and customs were ruthlessly stamped out.

The fathers travelled the countryside looking for promising locations for their missions. The choice of location was a matter of considerable attention and debate involving every level of the bureaucracy in Spain. Once a site was chosen, rudimentary buildings were constructed, generally with the help of the natives and then the Fathers began to preach to them.

After a very basic introduction to the fundamentals of

Christianity, the “neophyte” was baptized. From that moment on, he was a member of the community and did not have the liberty to withdraw. The converts lived in mission residences and followed a rigorous schedule of religious services and classes in a variety of subjects, particularly Spanish and religion. For a part of the day, they were also expected to work in the fields, for the missions were self supporting farming communities, many of which grew rich over the years.

The Fathers exercised total authority over the lives of the converts, regulating all aspects of their existence including their sexual life. Any disobedience was subject to severe retribution, including corporal punishment. Neophytes who managed to escape from the mission were hunted down like runaway slaves.

While this may sound distinctly negative, there were also some very positive aspects to mission life:

Natives who joined the mission had a permanent, dependable source of food, which they had not had before.

They learned trades which would be useful in the European-style community the Fathers hoped to build.

They acquired a degree of equality with the other members of the urban communities, something the unassimilated natives could not hope for.

Download the full edition or view it online

Manzanillo Sun’s eMagazine written by local authors about living in Manzanillo and Mexico, since 2009

You must be logged in to post a comment.