By Kirby Vickery on the September 2020 Edition

Tezcatlipoca (Fiery Mirror) was undoubtedly the Jupiter of the Nahua pantheon. He carried a mirror or shield, from which he took his name, and in which he was supposed to see reflected the actions and deeds of humankind. The evolution of this god, from the status of a spirit of wind or air, to that of the supreme deity of the Aztec people, presents many points of deep interest to students of mythology.

Originally a personification of the air, the source both of the breath of life and of the tempest, Tezcatlipoca possessed all the attributes of a god who presided over these phenomena. As the tribal god of the Tezcucans who had led them into the Land of Promise, and had been instrumental in the defeat of both the gods and men of the elder race they dispossessed, Tezcatlipoca naturally advanced so speedily in popularity and public honour that it was little wonder that, within a comparatively short space of time, he came to be regarded as a god of fate and fortune, and as inseparably connected with the national destinies.

Thus, from being the peculiar deity of a small band of Nahua immigrants, the prestige accruing from the rapid conquest made under his tutelary direction, and the speedily disseminated tales of the prowess of those who worshipped him, seemed to render him at once the most popular and the best feared god in Anahuac, therefore the one whose cult quickly over-shadowed that of other and similar gods.

Tezcatlipoca, Overthrower of the Toltecs

We find Tezcatlipoca intimately associated with the legends, which recount the overthrow of Tollan, the capital of the Toltecs. His chief adversary on the Toltec side is the god king Quetzalcoatl, whose nature and reign we will consider later, but whom we will now merely regard as the enemy of Tezcatlipoca. The rivalry between these gods symbolizes that which existed between the civilized Toltecs and the barbarian Nahua, and is well exemplified in the following myths.

Myths of Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca

In the days of Quetzalcoatl, there was abundance of everything necessary for subsistence. The maize was plentiful, the calabashes were as thick as one’s arm, and cotton grew in all colours without having to be dyed. A variety of birds of rich plumage filled the air with their songs, and gold, silver, and precious stones were abundant. In the reign of Quetzalcoatl, there was peace and plenty for all men.

But, this blissful state was too fortunate, too happy to endure. Envious of the calm enjoyment of the god and his people, the Toltecs, three wicked “necromancers”, plotted their downfall. The reference is of course to the gods of the invading Nahua tribes, the deities Huitzilopochtli, Titlacahuan or Tezcatlipoca, and Tlacahuepan.

These laid evil enchantments upon the city of Tollan, and Tezcatlipoca, in particular, took the lead in these envious conspiracies. Disguised as an aged man with white hair, he presented himself at the palace of Quetzalcoatl, where he said to the pages-in-waiting: “Pray present me to your master, the king. I desire to speak with him.”

The pages advised him to retire, as Quetzalcoatl was indisposed and could see no one. He requested them, however, to tell the god that he was waiting outside. They did so and procured his admittance.

On entering the chamber of Quetzalcoatl, the wily Tezcatlipoca simulated much sympathy with the suffering godking. “How are you, my son?” he asked. “I have brought you a drug which you should drink and which will put an end to the course of your malady.”

“You are welcome, old man,” replied Quetzalcoatl. “I have known for many days that you would come. I am exceedingly indisposed. The malady affects my entire system and I can use neither my hands nor feet.”

Tezcatlipoca assured him that, if he partook of the medicine which he had brought him, he would immediately experience a great improvement in health. Quetzalcoatl drank the potion, and at once felt much revived. The cunning Tezcatlipoca pressed another and still another cup of the potion upon him, and, as it was nothing but pulque, the wine of the country, he speedily became intoxicated, and was as wax in the hands of his adversary.

Tezcatlipoca and the Toltecs

Tezcatlipoca and the Toltecs

Tezcatlipoca, in pursuance of his policy inimical to the Toltec state, took the form of an Indian of the name of Toueyo (Toveyo), and bent his steps to the palace of Uemac, chief of the Toltecs in temporal matters. He had a daughter so fair that she was desired in marriage by many of the Toltecs, but her father refused her hand to one and all.

The princess, beholding the false Toueyo passing her father’s palace, fell deeply in love with him and, so tumultuous was her passion that she became seriously ill because of her longing for him. Uemac, hearing of her indisposition, bent his steps to her apartments, and inquired of her women the cause of her illness .

They told him that it was occasioned by the sudden passion, which had seized her, for the Indian who had recently come that way. Uemac at once gave orders for the arrest of Toueyo, and he was hauled before the temporal chief of Tollan.

“Whence come you?” inquired Uemac of his prisoner, who was very scantily attired.

“Lord, I am a stranger, and I have come to these parts to sell green paint,” replied Tezcatlipoca.

“Why are you dressed in this fashion? Why do you not wear a cloak?” asked the chief.

“My lord, I follow the custom of my country,” replied Tezcat-lipoca.

“You have inspired a passion in the breast of my daughter,” said Uemac. “What should be done to you for thus disgracing me?”

“Slay me; I care not,” said the cunning Tezcatlipoca.

“Nay,” replied Uemac, “for if I slay you my daughter will perish. Go to her and say that she may wed you and be happy.”

They told him that it was occasioned by the sudden passion, which had seized her, for the Indian who had recently come that way. Uemac at once gave orders for the arrest of Toueyo, and he was hauled before the temporal chief of Tollan.

“Whence come you?” inquired Uemac of his prisoner, who was very scantily attired.

“Lord, I am a stranger, and I have come to these parts to sell green paint,” replied Tezcatlipoca.

“Why are you dressed in this fashion? Why do you not wear a cloak?” asked the chief.

“My lord, I follow the custom of my country,” replied Tezcat-lipoca.

Now the marriage of Toueyo to the daughter of Uemac aroused much discontent among the Toltecs; and they mur mured among themselves, and said: “Wherefore did Uemac give his daughter to this Toueyo?” Uemac, having got wind of these murmurings, resolved to distract the attention of the Tol-tecs by making war upon the neighboring state of Coatepec.

The Toltecs assembled armed for the fray and, having arrived at the country of the men of Coatepec, they placed Toueyo in ambush with his body-servants, hoping that he would be slain by their adversaries. But Toueyo and his men killed a large number of the enemy and put them to flight. His triumph was celebrated by Uemac with much pomp. The knightly plumes were placed upon his head, and his body was painted with red and yellow, which is an honor reserved for those who distin-guished themselves in battle.

Tezcatlipoca’s next step was to announce a great feast in Tollan, to which all the people for miles around were invited. Great crowds assembled and danced and sang in the city to the sound of the drum. Tezcatlipoca sang to them and forced them to accompany the rhythm of his song with their feet.

Faster and faster the people danced, until the pace became so furious that they were driven to madness, lost their footing, and tumbled pell-mell down a deep ravine, where they were changed into rocks. Others, in attempting to cross a stone bridge, precipitated themselves into the water below, and were changed into stones.

Tezcatlipoca ([teskatɬiˈpo ː ka]) was a central deity in Aztec mythology. He was associated with many concepts. Some of these are the night sky, the night winds, hurricanes, the north, the earth, obsidian, enmity, discord, rulership, divination, tempta-tion, sorcery, beauty, war and strife. His name in the Nahuatl language is often translated as “Smoking Mirror” because of his connection to obsidian, the material from which mirrors were made in Mesoamerica and which was used for shamanic rituals.

He had many names in context with different aspects of his de-ity: Titlacauan (“We are his Slaves”), Ipalnemoani (“He by whom we live”), Necoc Yaotl (“Enemy of Both Sides”), Tloque Nahuaque (“Lord of the Near and the Nigh”) and Yohualli Èecatl (Night, Wind), Ome acatl (“Two Reed”), Ilhuicahua Tlalticpaque (“Possessor of the Sky and Earth”).

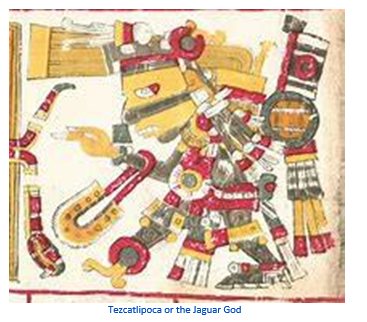

On pictures, he was usually drawn with a black and a yellow stripe painted across his face. He is often shown with his right foot replaced with an obsidian mirror or a snake an allusion to the creation myth in which he loses his foot battling with the Earth Monster.

Sometimes the mirror was shown on his chest, and sometimes smoke would come from the mirror. Tezcatlipocas Nagual, his animal counterpart, was the jaguar and his Jaguar aspect was the deity Tepeyollotl “Mountainheart”.

The Tezcatlipoca figure goes back to earlier Mesoamerican deities worshipped by the Olmec and Maya. Similarities exist with the patron deity of the K’iche’ Maya as described in the Popol Vuh. A central figure of the Popol Vuh was the god Tohil, whose name means “obsidian”, and who was associated with sacrifice. Also, the Classic Maya god of rulership and thunder, known to modern Mayanists as “God K”, or the “Manikin Scep-ter”, and to the classic Maya as K’awil, was shown with a smok-ing obsidian knife in his forehead and one leg replaced with a snake.

Tezcatlipoca and Quetzalcoatl

Tezcatlipoca was often described as a rival of another important god of the Aztecs, the culture hero, Quetzalcoatl. In one version of the Aztec creation account the myth of the Five Suns, The first creation, “The sun of the Earth” was ruled by Tezcatlipoca but destroyed by Quetzalcoatl when he struck down Tezcatlipoca who then transformed into a jaguar. Quet-zalcoatl became the ruler of the following creation, “Sun of Water”, and Tezcatlipoca destroyed the third creation, “Sun of Wind” by striking down Quetzalcoatl.

Tepeyollotl 1

When Hernán Cortés first landed close to what is now Veracruz, Mexico, in 1519, the last thing he was interested in was the preservation of the knowledge and history of the Mesoamerican culture(s) as he went through and defeated them in battle, both by war and by trickery, to obtain their gold. Two things happened, which for the love of history, turned out to be good. The first was that the Aztecs did not want anyone knowing where they came from and hid or destroyed all their books (yes, they had a written language) showing where they came from. Although a blessing for the Aztecs, this has turned into a modern search for where they and the rest of the Central American Tribes and Empires came from. (It has even gotten silly.

When Hernán Cortés first landed close to what is now Veracruz, Mexico, in 1519, the last thing he was interested in was the preservation of the knowledge and history of the Mesoamerican culture(s) as he went through and defeated them in battle, both by war and by trickery, to obtain their gold. Two things happened, which for the love of history, turned out to be good. The first was that the Aztecs did not want anyone knowing where they came from and hid or destroyed all their books (yes, they had a written language) showing where they came from. Although a blessing for the Aztecs, this has turned into a modern search for where they and the rest of the Central American Tribes and Empires came from. (It has even gotten silly.

The Olmecs were the first and they did not leave a written language. So, because of the shape of the Olmec features on their giant heads they carved, one group from Africa has claimed inheritance and want the world to turn all of Central America, including Mexico, to them.

The second was the Catholic Church that decreed that all the books of the “Heathen” depicting their ‘false’ gods be destroyed. What is good was that there were a few priests that didn’t follow the order and some of them even sat some of the ‘savages’ down to write of their culture, history and religion. These have become the Codices, which modern day people are always quoting.

These, it seems, did not turn up immediately in Spanish hands, but later, from various churches in France and other countries. It is these Codices that have given historians and archeologists a firm foundation in the Mesoamerican cultures to include their languages, beliefs, culture, and mythology which they may not have valued, as such, but have turned into something a lot better than the much sought after gold Hernan was originally after.

There are volumes of information on the Mesoamerican Gods, most of which concern an Aztec Central God named Quetzalcoatl. He was the brother of Tezcatlipoca, depicted in the codex Rios in the aspect of a Jaguar in this form he was called Tepeyollotl.

In later myths, the four gods who created the world, Tezcat-lipoca, Quetzalcoatl, Huitzilopochtli and Xipe Totec were referred to respectively as the Black, the White, the Blue and the Red Tezcatlipoca. The four Tezcatlipocas were the sons of Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl, lord and lady of the duality, and were the creators of all the other gods, as well as the world and man. [Confused yet?]

We can look at him this way, too: Tezcatlipoca was often de-scribed as a rival of another important god of the Aztecs, the culture hero, Quetzalcoatl.

In one version of the Aztec creation account, there is a myth of the Five Suns, where the word ‘Sun’ is actually a singular creation of a ‘world.’ The first creation, “The Sun of the Earth”, was ruled by Tezcatlipoca but destroyed by Quetzalcoatl when he struck down Tezcatlipoca who then transformed into a jaguar.

Quetzalcoatl became the ruler of the following creation “Sun of

Water”, and Tezcatlipoca destroyed the third creation, “The Sun of Wind”, by striking down Quetzalcoatl.

Here is a quick story which is a good example of their rivalry:

To the Toltecs, Tezcatlipoca was their head God. The Aztecs considered the Toltec their intellectual equal and also revered Tezcatlipoca but not as much as Quetzalcoatl. And that is what set the two gods up as adversaries.

—

Kirby was born in a little burg just south of El Paso, Texas called Fabens. As he understand it, they we were passing through. His history reads like a road atlas. By the time he started school, he had lived in five places in two states. By the time he started high school, that list went to five states, four countries on three continents. Then he joined the Air Force after high school and one year of college and spent 23 years stationed in eleven or twelve places and traveled all over the place doing administrative, security, and electronic things. His final stay was being in charge of Air Force Recruiting in San Diego, Imperial, and Yuma counties. Upon retirement he went back to New England as a Quality Assurance Manager in electronics manufacturing before he was moved to Production Manager for the company’s Mexico operations. He moved to the Phoenix area and finally got his education and ended up teaching. He parted with the university and moved to Whidbey Island, Washington where he was introduced to Manzanillo, Mexico. It was there that he started to publish his monthly article for the Manzanillo Sun. He currently reside in Coupeville, WA, Edmonton, AB, and Manzanillo, Colima, Mexico, depending on whose having what medical problems and the time of year. His time is spent dieting, writing his second book, various articles and short stories, and sightseeing Canada, although that seems to be limited in the winter up there.