By Manzanillo Sun Writer from the January 2011 Edition

Part 3: The War

The Mexican-American War, which broke out in May 1846, pitted a very large, modern nation with a state-of-the-art military establishment against a pre-industrial society of severely limited resources. The result was essentially a foregone conclusion. The powerful American forces attacked simultaneously on several fronts and the antiquated, un-mechanized Mexican military, in spite of fighting courageously, simply did not have the means to combat them effectively.

Northern Mexico

The declaration of war on May 13, 1846, found hostilities already underway on the Texas Border. Mexican forces in the town of Matamoros had already begun bombarding Fort Texas across the Rio Grande on May 3. The Americans responded in kind, but the result was a stand-off. General Zachary Taylor, camped on the banks of the Rio Grande, marched to the relief of the fort with a force of 2400 men, but was intercepted by the Mexican General Arista.

At the battles of Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma, the Americans drove back the Mexicans. Taylor then occupied Matamoros and Camargo and marched on Monterrey.

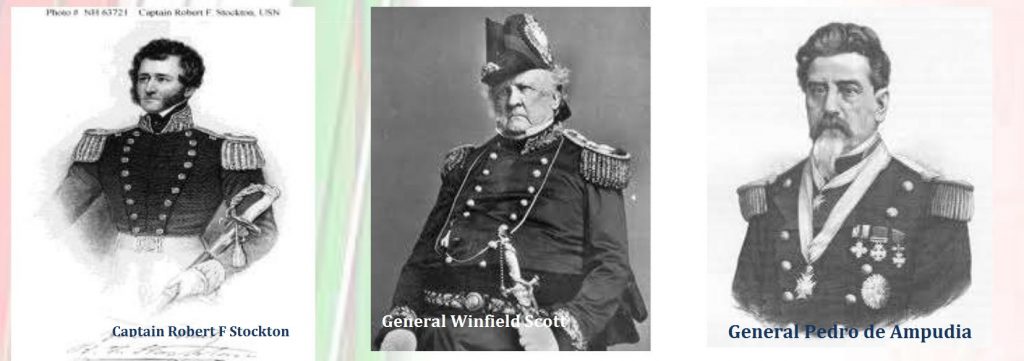

The siege of Monterrey was difficult with numerous losses for both sides. The Americans found their heavy artillery ineffective against the massive stone walls of the city as General Pedro de Ampudia was able to hold them off for a lengthy period. The US Army finally penetrated into the city, but their officers, many of them trained in traditional warfare at West Point, had no knowledge of urban fighting. They led their men in parade formation straight down the principal arteries of the city, where they were ruthlessly cut down by Mexican forces hidden inside the old stone houses.

The Americans, however, rapidly adapted to the unfamiliar conditions and eventually prevailed. In the end, Ampudia’s forces were cornered in the Zocalo of the city where American Howitzers threatened to obliterate them. Faced with the certain annihilation of his army, Ampudia surrendered. Taylor allowed him to evacuate the city with his men and agreed to an eight-week truce.

President Polk overruled Taylor on the question of the truce, insisting that he pursue Ampudia in his retreat. Taylor therefore violated his own truce and occupied the city of Saltillo, southwest of Monterrey. At this point, President Santa Anna, who believed the loss of Monterrey was due to

Ampudia’s incompetence, relieved him of his command and took charge himself. He marched northwards to meet Taylor at the head of a 20,000 man army. Taylor was ensconced in a mountain pass near Buena Vista with only 4600 men, but he held an advantageous position on high ground and was able to hold his own. Intense hand to hand fighting resulted in heavy losses for both sides. For a time, it appeared that

Santa Anna’s heavily superior numbers would carry the day. But news came of fighting in Mexico City and Santa Anna rushed back to the city, leaving Taylor alone in the field and in control of all of northern Mexico.

The Battle of Buena Vista was reported in the American press as a glorious victory and was an important element in

Taylor’s election as President in 1848.

* * * * *

California

When news of the declaration of war reached California, a small group of about 30 Americans raised the “Bear Flag” at Sonoma and proclaimed the “Republic of California” independent of Mexico. Within a week, Captain John Fremont, at the head of a force of only 60 US soldiers, took control of the fort on behalf of the United States.

At the same time, Commodore John Sloat, commanding the US fleet in the Pacific, landed a small force at Monterey1 (the capital of colonial California) and took the city almost without resistance. San Francisco was occupied a few days later.

In August 1846, Commodore Robert Stockton, who had taken over Sloat’s command, launched a highly aggressive campaign down the California coast in pursuit of the Mexican Governor, Pio Pico and General José Castro, who had both fled towards the south. Stockton landed a force of 50 US Marines at San Pedro and managed to occupy the village of Los Angeles without firing a shot. It appeared that California had been annexed to the United States almost without bloodshed.

But the US Generals had reckoned without the Californios, the citizens of Mexican California. Acting on their own, without help from the Mexican Government, a band of Californios re-took Los Angeles from the small garrison Stockton had left behind. In October 1846, they defeated a force of 300 marines near San Pedro.

1. Monterey, a small city on the California coast about 150 miles south of San Francisco should not be confused with Monterrey, a much larger city in north-central Mexico, Meanwhile, a force of 139 dragoons, commanded by General Stephen Kearney, had left Fort Leavenworth, Kansas when war was declared and had been marching overland since May 1846. On December 6, Kearney reached the West Coast just in time to join the fight against the Californios. The two forces met near San Diego and Kearney, badly outnumbered, lost 22 of his men. The Californios continued to harass

Kearney’s small army for several days until Commodore

Stockton was able to arrive with a relief force. Together,

Kearney and Stockton’s marines marched north to Los Angeles where they met up with Captain Fremont and his band. The three combined forces totalled 607 men. But they were able to defeat an even smaller force of 300 Californios at the battles of Rio San Gabriel and La Mesa (near Los Angeles). On January 12, 1847, the last

Californios were subdued and the conquest of California was complete.

With California safely in American hands, Commodore Stockton continued his advance down the Pacific coast, capturing La Paz and Mazatlan. He then sailed up the Gulf of California as far north as Guaymas, which he also took.

* * * * *

Central Mexico

The main assault of the war was led by General Winfield Scott against central Mexico. In the first amphibious operation in American history, Scott landed at Veracruz with 12,000 men on March 9, 1847 with orders to begin the invasion of the Mexican heartland. For forty-eight hours, Scott subjected Veracruz to heavy bombardment in spite of the many civilian casualties involved. The defending force of 3400 men under General Juan Morales fought valiantly, but was no match for the vastly superior American force. After 12 days of siege, with water and supplies running low and decomposing bodies clogging the streets, General Morales surrendered.

The Stars and Stripes was hoisted on the flagpole in the central square and Scott was free to continue his push into the heart of Mexico.

He advanced with 8500 men towards Mexico City. President Santa Anna, in the capital received news of the invasion and set out with a force of 12,000 men to stop Scott. He intercepted the Americans at Cerro Gordo near Jalapa. A combination of military errors by Santa Anna and skilful manoeuvring by Scott gave the victory to the Americans. Santa Anna withdrew to Puebla where the citizens held him in such low esteem that they declined his offer of defence. Puebla, therefore, surrendered to General Scott without firing a shot. The way was open to Mexico City

The defence of the city was greatly impeded by internecine quarrels. Certain elements of the military refused to take orders from a government they distrusted. As a result, only a haphazard and disorganized resistance was offered to the advancing Americans. On the level of the ordinary soldier, however, there was a firm determination to defend the national capital. Intense hand-to-hand fighting occurred in the vicinity of the city with major battles at Contreras and Churubuscu. At Churubuscu, in particular, the Mexicans distinguished themselves by their bravery, refusing again and again to yield to a much larger American force. But in the end, it was superior numbers and technology that carried the day.

On September 7, 1847, Scott stormed the fortress of Molina del Rey inside the city. It was the bloodiest encounter of the war, with 2000 Mexican casualties and 700 Americans. With Molina del Rey in American hands, there remained only one fortified place in the city: Chapultepec Castle. The castle was defended by only 1000 regular troops and the cadets of the military academy. After an epic struggle, the defenders were reduced to a handful of men, including the young cadets. The cadets (the ninos heroes of legend) fought to the last man rather than surrender. Once again, larger numbers and modern weaponry proved stronger. With the fall of the castle, General Scott was in command of the city.

* * * * *

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

With many of its major cities occupied, including the Capital; with its military in disarray and internal dissension inside the government, Mexico had little choice but to ask for peace at any price. The American negotiators drove a hard bargain. In the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed on February 2, 1848, Mexico relinquished all claim to Texas and agreed to fix the border at the Rio Grande. In addition, very large territories in north-western Mexico were ceded to the United States. Today, those territories comprise the States of California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico, as well as parts of Colorado, Oklahoma, and

Wyoming. Mexico had sacrificed fully 55% of its original territory. (see map showing territories ceded in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.)

In 1853, James Gadsden, the US Ambassador to Mexico, negotiated the purchase of an additional tract of 29,670 square miles (roughly the size of Scotland) which was detached from northern Mexico and added to the States of Arizona and New Mexico. (See “Gadsden Purchase” on map.)

* * * * *

The Mexican-American War was clearly a disaster for Mexico. At first glance, it appears to have been a triumph for America. But closer examination might yield a more nuanced opinion. The profound distrust in the US between Northerners and Southerners, already present at the time of Independence, was greatly exacerbated by the acrimonious debate over western expansion. Hatreds that had been smouldering for decades broke into sudden flame under the strain of the Mexican war. They were to explode into all-out war in less than 15 years. Some might say that Mexico’s disaster led directly to America’s greatest misfortune. Certain historians have affirmed that the seeds of the Civil War were planted on the banks of the Rio Grande.

* * * * *

Download the full edition or view it online

Manzanillo Sun’s eMagazine written by local authors about living in Manzanillo and Mexico, since 2009

You must be logged in to post a comment.