By Tommy Clarkson from the September 2016 Edition

Queen of the Night, Selenicereus grandifloras, Selenicereus chrysocardium, Selenicereus hamatus, Selenicer-eus knuthianus or Selenicereus hallensis (In all candor, I’ m unsure!)

Family: Cactaceae

Also known as: Moonlight Cactus, Night-blooming Cereus, Large-flowering Cactus or Sweet-scented Cactus (Even with several cacti and succulent books in my library, several knowledgeable botanical friends from whom to often draw facts and data, as well as the totality of information available on the internet, I still have been unable to confirm with absolute assuredness which, exact and specific, cactus we recently found!)

Also known as: Moonlight Cactus, Night-blooming Cereus, Large-flowering Cactus or Sweet-scented Cactus (Even with several cacti and succulent books in my library, several knowledgeable botanical friends from whom to often draw facts and data, as well as the totality of information available on the internet, I still have been unable to confirm with absolute assuredness which, exact and specific, cactus we recently found!)

Vacationing away from our homes in Manzanillo for a bit, pal Dave and I left our ladies to take a normal, morning walk. It was in the mountainous, Ajijic area, around 5,000 feet (1,524 meters) in elevation. (And yes, this chubby, old guy was struggling with the steeper upgrades on the cobblestoned roads!)

Obviously having seen me taking pictures of various higher altitude plants, a small gaggle of kids excitedly yelled at us, pointing into a vacant lot. When we went to investigate the source of their active enthusiasm, the accompanying pictures reflect what we saw.

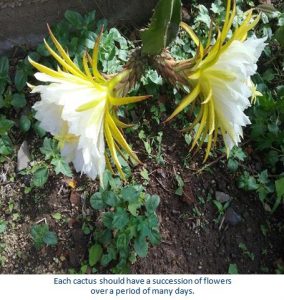

Prior to this, I’d heard about, but had not yet seen, these magnificent, sweetly-scented, up to twelve inches  (30.48 cm) across, blossoms. This, in large part comes from the fact that, in cultivation, they seldom flower. But of this beauty “in the wild”, I can but only say, “Wowie-kazowie”! Dramatic would be a gross understatement in articulating one’s first response upon seeing them. These stunningly, beautiful blooms are all they’re billed and much more!

(30.48 cm) across, blossoms. This, in large part comes from the fact that, in cultivation, they seldom flower. But of this beauty “in the wild”, I can but only say, “Wowie-kazowie”! Dramatic would be a gross understatement in articulating one’s first response upon seeing them. These stunningly, beautiful blooms are all they’re billed and much more!

The Queen of the Night is from the Selenicereus genus, of which all are night bloomers. (Appropriately, the generic name comes from Selene, the Greek moon goddess, and cereus, meaning candle in Latin, which refers to the nocturnal nature of its flowers.) As they realize their beauty at night, they are pollinated by moths and, sometimes, bats.

For the most part, they grow naturally in the forests of Mexico and, possibly south through Central America into South America and even up in the Caribbean. All of them have long necked, somewhat strangely, summer blooming flowers. These grow near their stem tips and produce spiny fruits that look similar to plums, reaching four inches (10.16 cm) in diameter.

Its flower buds form on trailing stems in mid to late summer, taking several weeks to grow. The, rather weird-looking, buds may be up to nearly eight inches (20.32 cm) long. The flowers last but one night and have little appreciation for the sun. (By around 11:00 AM when I took Patty back to see these beauties, they’d already started to wilt.)

However, the good news is that on healthy plants there should be a succession of flowers over a period of many days, so set your alarm to get up the next night!

Selenicereus species are easily propagated by seeds or cuttings. In warmer climes, they can be watered and grown year-round. They are sometimes used as rootstock for grafting other species. For the most part, they’re shade lovers, but wait until maturity to bloom. However, from all I’ve been able to discern, this intriguing cactus grows rather fast. But, as noted, there are no few different names attributed to this plant. In fact, upon perusing The Plant List, online, one finds no less than thirty-three different synonyms!

Selenicereus species are easily propagated by seeds or cuttings. In warmer climes, they can be watered and grown year-round. They are sometimes used as rootstock for grafting other species. For the most part, they’re shade lovers, but wait until maturity to bloom. However, from all I’ve been able to discern, this intriguing cactus grows rather fast. But, as noted, there are no few different names attributed to this plant. In fact, upon perusing The Plant List, online, one finds no less than thirty-three different synonyms!

They all are, generally, epiphytic climbers. (Though I’ve read of this species referred to as a “functional epiphyte”, which means that it can thrive either as an epiphyte or a terrestrial plant.

As a result, they grow harmlessly on other plants or structures

(in this case an old brick wall) deriving their moisture and nutrients from the air, rain and, occasionally, vegetative debris around it.

It is important to note that epiphytes differ markedly from parasites such as Mistletoe and the Corpse Flower Yuk!

(At this juncture, it is rather important to discredit the common belief (which I too, once held) that orchids are parasitic.) Epiphytes are generally friendly sorts, growing on other plants for physical support and, not normally, negatively affecting their host – most impolite and discourteous to say the least!

The slim if not outright skinny stems of the Selenicereus grandifloras vary with deep to shallow ribs (which add to its an-gular appearance), can be either bristly or broad in nature and have spines ranging from pale to darkish. Obviously, as an epiphyte, it holds itself in place through strong aerial roots.

By whatever Latin name it’s known, it’s a beauty!

Download the full edition or view it online

—

Tommy Clarkson is a bit of a renaissance man. He’s lived and worked in locales as disparate as the 1.2 square mile island of Kwajalein to war-torn Iraq, from aboard he and Patty’s boat berthed out of Sea Bright, NJ to Thailand, Germany, Hawaii and Viet Nam; He’s taught classes and courses on creative writing and mass communications from the elementary grades to graduate level; He’s spoken to a wide array of meetings, conferences and assemblages on topics as varied as Buddhism, strategic marketing and tropical plants; In the latter category he and Patty’s recently book, “The Civilized Jungle” – written for the lay gardener – has been heralded as “the best tropical plant book in the last ten years”; And, according to Trip Advisor, their spectacular tropical creation – Ola Brisa Gardens – is the “Number One Tour destination in Manzanillo”.