By Manzanillo Sun Writer from the January 2014 Edition

I am 67 and, as most people my age, have seen death take friends, family, and strangers both peacefully or with violence. We each get involved to some extent or other depending on the many aspects of each death.

We’re told by highly educated people that dwelling on them isn’t good for us and that’s probably really good advice.

We learn that for every culture there are some twists and turns concerning each societal view of death be it religious, social, personal, or slightly demented. I found this story which provided elucidation to some of the Aztec’s views on the subject. Is it a true story or just something fabricated by the all powerful priests of that culture and time which glorifies their views? You decide.

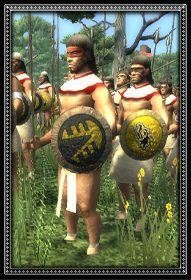

Just before the arrival of the Spanish the Aztec under Montezuma were considered war-like and just plain vicious. Part of that was true and was being generated by the priest hierarchy as a means to keep the populous opinion of them in check and allow them the power they needed to stay on top. As crude as it sounds to us they would put the call out for more sacrifice every time things settled down to engage the people and obtain more control.

The Romans did it as did Hitler and others throughout western history. The end result was that the Aztec priesthood kept and gained their power and the Aztec nation grew through war and plunder. As may be imagined regarding a community where human sacrifice was rife, tales concerning those who were consigned to this dreadful fate were abundant.

Perhaps the most striking of these is that relating to a noble Tlascalan warrior named Tlalhuicole. He was captured in combat by the troops of Montezuma by guile rather that straight fighting. [I’ll have to find that story. Ed.] War had broken out between the Huexotzincans and the Tlascalans.

The Aztec nation was an ally of the Huexotzincans so they fought on that side. Tlalhuicole was so renowned for his fighting prowess that the mere mention of his name generally deterred any Mexican hero or want-to-be from attempting his capture. But captured he was and taken to Mexico in a cage. He was presented to the Emperor Montezuma, who, on learning of his name and renown, gave him his liberty and overwhelmed him with honors.

Montezuma thought so highly of this warrior that he even gave him his freedom and permission to return to his own country. This was never heard of before for any captive. The warrior Tlalhuicole refused all of this saying that he would prefer to be sacrificed to the gods, according to the Aztec custom. Montezuma, on the other hand flat denied this request because of his regard for this warrior.

At this time war broke out between Mexico (the Aztecs) and the Tarascans who controlled the land west of Mexico City all the way through the present state of Colima to the Pacific ocean. At this juncture, Montezuma announced the appointment of Tlalhuicole as chief of his expeditionary force. He accepted the command, marched against the Tarascans, and, after having totally defeated them, returned to Mexico laden with an enormous booty and crowds of slaves.

The city rang with his triumph. Montezuma begged him to become a Mexican citizen, but he said that any such move on his part would prove that he was a traitor to his own country and he wouldn’t do it. Montezuma then once more offered him his liberty to return home to Tlascala, but this was also strenuously refused. He kept telling Montezuma that having undergone the disgrace of defeat and capture that he should be terminated. He begged Montezuma to end his unhappy existence by sacrificing him to the gods. This would end the dishonor he felt in living on after having undergone defeat, and at the same time fulfilling the highest aspiration of his life which was to die the death of a warrior on the stone of combat.

Montezuma, a strong proponent of Aztec chivalry, was touched by his request. He agreed with him that he had chosen the most fitting fate for a hero, and ordered him to be chained to the stone of combat, the blood-stained Temalacatl. The most renowned of the Aztec warriors were pitted against him, and the emperor himself graced the tournament with his presence.

Tlalhuicole bore himself in the combat like a lion, slew eight warriors of renown, and wounded more than twenty. But at last he fell, covered with wounds, and was hauled by the exulting priests to the altar of the terrible war-god Huitzilopochtli, to whom his heart was offered up.

Download the full edition or view it online

Manzanillo Sun’s eMagazine written by local authors about living in Manzanillo and Mexico, since 2009

You must be logged in to post a comment.