By Kirby Vickery from the August 2016 Edition

[The following, extracted from Tezozomoc’s Chronica Mexicana, reproduced in Lord Kingsborough’s great  work, is valuable as giving unique facts regarding the Aztec mythology, as is the Teatro Mexicana of Vetancurt, published at Mexico in 1697-98.]

work, is valuable as giving unique facts regarding the Aztec mythology, as is the Teatro Mexicana of Vetancurt, published at Mexico in 1697-98.]

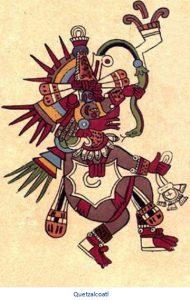

In the days of Quetzalcoatl there was abundance of everything necessary for subsistence. The maize was plentiful, the calabashes were as thick as one’s arm, and cotton grew in all colors without having to be dyed. In the reign of Quetzalcoatl there was peace and plenty for all men.

Envious of the calm enjoyment of the god and his people the Toltecs, three wicked “necromancers” plotted their downfall. The reference is of course to the gods of the invading Nahua tribes, the deities Huitzilopochtli, Titlacahuan or Tezcatlipoca, and Tlacahuepan. These laid evil enchantments upon the city of Tollan, and Tezcatlipoca in particular took the lead in these envious conspiracies. Disguised as an aged man with white hair, he presented himself at the palace of Quetzalcoatl, where he said to the pages in waiting: “Pray present me to your master the king I desire to speak with him.”

The pages advised him to retire, as Quetzalcoatl was indisposed and could see no one. He requested them, however, to tell the god that he was waiting outside. They did so, and procured his admittance.

The pages advised him to retire, as Quetzalcoatl was indisposed and could see no one. He requested them, however, to tell the god that he was waiting outside. They did so, and procured his admittance.

On entering the chamber of Quetzalcoatl, the wily Tezcatlipoca simulated much sympathy with the suffering god-king. “How are you, my son?” he asked. “I have brought you a drug which you should drink, and which will put an end to the course of your malady.”

“You are welcome, old man,” replied Quetzalcoatl.

I have known for many days that you would come. I am exceedingly indisposed. The malady affects my entire system, and I can use neither my hands nor feet.”

Tezcatlipoca assured him that if he partook of the medicine which he had brought him he would immediately experience a great improvement in health. Quetzalcoatl drank the potion, and at once felt much revived. The cunning Tezcatlipoca pressed another and still another cup of the potion upon him, and as it was nothing but pulque, the wine of the country, he speedily became intoxicated, and was as wax in the hands of his adversary.

experience a great improvement in health. Quetzalcoatl drank the potion, and at once felt much revived. The cunning Tezcatlipoca pressed another and still another cup of the potion upon him, and as it was nothing but pulque, the wine of the country, he speedily became intoxicated, and was as wax in the hands of his adversary.

The various classes of the Aztec priesthood were in the habit of addressing the several gods to whom they ministered as “omnipotent,” “endless,” “invisible,” “the one god complete in perfection and unity,” and “the Maker and Molder of All.” These appellations they applied not to one Supreme Being, but to the individual deities to whose service they were attached. It may be thought that such a practice would be fatal to the evolution of a single and universal god. But there is every reason to believe that Tezcatlipoca, the great god of the air, like the Hebrew Jahveh, also an air-god, was fast gaining precedence of all other deities, when the coming of the white man put an end to his chances of sovereignty.

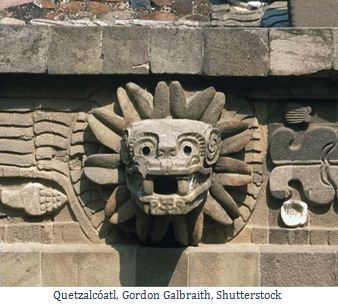

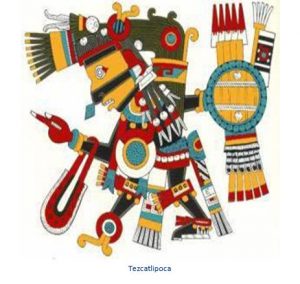

Tezcatlipoca (Fiery Mirror) was undoubtedly the Jupiter of the Nahua pantheon. He carried a mirror or shield, from which he took his name, and in which he was supposed to see reflected the actions and deeds of mankind. The evolution of this god from the status of a spirit of wind or air to that of the supreme deity of the Aztec people presents many points of deep inter-est to students of mythology.

Tezcatlipoca (Fiery Mirror) was undoubtedly the Jupiter of the Nahua pantheon. He carried a mirror or shield, from which he took his name, and in which he was supposed to see reflected the actions and deeds of mankind. The evolution of this god from the status of a spirit of wind or air to that of the supreme deity of the Aztec people presents many points of deep inter-est to students of mythology.

Originally the personification of the air, the source both of the breath of life and of the tempest, Tezcatlipoca possessed all the attributes of a god who presided over these phenomena. As the tribal god of the Tezcucans who had led them into the Land of Promise, and had been instrumental in the defeat of both the gods and men of the elder race they dispossessed, Tezcatlipoca naturally advanced so speedily in popularity and public honor that it was little wonder that within a comparatively short space of time he came to be regarded as a god of fate and fortune, and as inseparably connected with the national destinies.

Thus, from being the peculiar deity of a small band of Nahua immigrants, the prestige accruing from the  rapid conquest made under his tutelary direction, the speedily disseminated tales of the prowess of those who worshipped him seemed to render him at once the most popular and the best feared god in Anahuac. Therefore, his was the one whose cult quickly over-shadowed that of other and similar gods.

rapid conquest made under his tutelary direction, the speedily disseminated tales of the prowess of those who worshipped him seemed to render him at once the most popular and the best feared god in Anahuac. Therefore, his was the one whose cult quickly over-shadowed that of other and similar gods.

We find Tezcatlipoca intimately associated with the legends which recount the overthrow of Tollan, the capital of the Toltecs. His chief adversary on the Toltec side is the god king Quetzalcoatl. The rivalry between these gods symbolizes that which existed between the civilized Toltecs and the barbarian Nahua.

Tezcatlipoca was much more than a mere personification of wind, and if he was regarded as a life-giver, he had also the power of destroying existence. In fact, on occasion he appears as an inexorable death-dealer, and as such was styled Nezahualpilli (The Hungry Chief) and Yaotzin (The Enemy). Perhaps one of the names by which he was best known was Telpochtli (The Youthful Warrior), from the fact that his reserve of’ strength, his vital force, never diminished, and that his youthful and boisterous vigor was apparent in the tempest.

Tezcatlipoca was usually depicted as holding in his right hand a dart placed in an atlatl (spear-thrower), and his mirror-shield with four spare darts in his left. This shield is the symbol of his power as judge of mankind and upholder of human justice.

The Aztecs pictured Tezcatlipoca as rioting along the highways in search of persons on whom to wreak his vengeance, as the wind of night rushes along the deserted roads with more seeming violence than it does by day. Indeed one of his names, Yoalli Ehecatl, signifies “Night Wind.” Benches of stone, shaped like those made for the dignitaries of the Mexican towns, were distributed along the highways for his special use, that on these he might rest after his boisterous journeying. These seats were concealed by green boughs, beneath which the god was sup-posed to lurk in wait for his victims. But if one of the persons he seized overcame him in the struggle, he might ask whatever boon he desired, secure in the promise of the deity that it should be granted forthwith.

It was supposed that Tezcatlipoca had guided the Nahua, and especially the people of Tezcuco, from a more northerly clime to the valley of Mexico. But he was not a mere local deity of Tezcuco, his worship being widely celebrated throughout the country. His exalted position in the Mexican pantheon seems to have won for him especial reverence as a god of fate and for-tune. The place he took as the head of the Nahua pantheon brought him many attributes which were quite foreign to his original character.

Fear and a desire to exalt their tutelary deity will impel the devotees of a powerful god to credit him with any or every quality, so that there is nothing remarkable in the spectacle of the heaping of every possible attribute, human or divine, upon Tezcatlipoca. His priestly caste far surpassed in power and in the breadth and activity of its propaganda the priesthoods of the other Mexican deities. To it is credited the invention of many of the usages of civilization, and that it all-but-succeeded in making his worship universal is pretty clear.

The other gods were worshipped for some special purpose, but the worship of Tezcatlipoca was regarded as compulsory, and to some extent as a safeguard against the destruction of the universe, a calamity the Nahua had been led to believe might occur through his agency.

He was known as Moneneque (The Claimer of Prayer), and in some of the representations of him an ear of gold was shown suspended from his hair, toward which small tongues of gold strained upward in appeal of prayer. In times of national danger, plague, or famine, universal prayer was made to Tezcatlipoca.

The heads of the community repaired to his teocalli (temple) accompanied by the people en masse, and all prayed earnestly together for his speedy intervention. The prayers to Tezcatlipoca, still extant, prove that the ancient Mexicans fully believed that he possessed the power of life and death, and many of them are couched in the most piteous terms.

Download the full edition or view it online

—

Kirby was born in a little burg just south of El Paso, Texas called Fabens. As he understand it, they we were passing through. His history reads like a road atlas. By the time he started school, he had lived in five places in two states. By the time he started high school, that list went to five states, four countries on three continents. Then he joined the Air Force after high school and one year of college and spent 23 years stationed in eleven or twelve places and traveled all over the place doing administrative, security, and electronic things. His final stay was being in charge of Air Force Recruiting in San Diego, Imperial, and Yuma counties. Upon retirement he went back to New England as a Quality Assurance Manager in electronics manufacturing before he was moved to Production Manager for the company’s Mexico operations. He moved to the Phoenix area and finally got his education and ended up teaching. He parted with the university and moved to Whidbey Island, Washington where he was introduced to Manzanillo, Mexico. It was there that he started to publish his monthly article for the Manzanillo Sun. He currently reside in Coupeville, WA, Edmonton, AB, and Manzanillo, Colima, Mexico, depending on whose having what medical problems and the time of year. His time is spent dieting, writing his second book, various articles and short stories, and sightseeing Canada, although that seems to be limited in the winter up there.