By Dan and Lisa Goy from the December 2016 Edition

We were off at 8:30 am sharp to Palenque, first on Hwy 186 starting out from the campground near Escarcega. The drive was good, although we always move slowly when we encounter villages, travelling from the state of Quintana Roo thru Tabasco into Chiapas.

We had quite the greeting when entering Chiapas, no “Welcome to Chiapas”, instead we drove into a massive security facility and submitted passports, vehicle registration, import permits and VIN Numbers were checked. Interesting to say the least.

We arrived in Palenque, the town, and decided to return for groceries. Our destination was the MayaBell Campground which has beautiful surroundings, right in the heart of the jungle with clean washrooms, showers, a pool and a nice restaurant. We set up and went for a swim, then into town for some supplies.

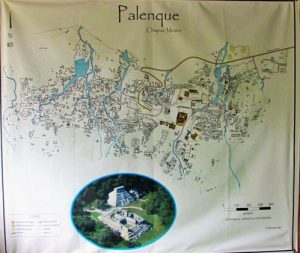

The next morning, we were off to the Palenque Archeological site, led by the Steinforts, which is exceptional to see in this jungle setting. With no big crowds and mostly European tourists, the site itself is massive. To date only 5% of the existing structures have been uncovered, sitting on approximately 1 square mile.

Over 1500 structures remain beneath the jungle on the mountainside into the valley. The weather was changing and, before you knew it, the rain was upon us. Lisa and I went swimming in the pool back at MayaBell during one of these downpours. What a fabulous experience! It rained heavily off and on the rest of the afternoon and overnight, however we were greeted with lots of blue sky in the morning.

At 10:00 am the group headed out in the Baja Amigos Colectivo to Misal Ha, a very popular waterfall and possible swim-ming location not far away from Palenque. We enjoyed some terrific scenery on our short drive as we climbed for 200’ (75m) to almost 1000’ (300m) into the jungle.

We arrived at the sign and were greeted by some folks collecting $10 pesos per person for entry, ejido members. Travelling another 2 or 3 km we came across another collection, this time $20 pesos per person. Apparently the road to the falls crosses two (2) different ejido lands, hence the two different collection points. $30 pesos is just more than $2 Canadian or $1.50 USD, certainly not much. The falls were worth every penny or, in this case, peso.

They were very impressive as they thundered down, at least 100’, probably more than 30m. There was a walkway behind them that was deafening. You walk up the other side from be-low however, with the recent heavy rain, these stairs were also a waterfall. It looked a bit sketchy. Swimming was possible but the walk to the pools was very slippery and the water very tur-bid, also likely from the heavy rains. Kelly found some great bumper stickers at a little shop on site.

We returned back to Palenque as some folks needed an ATM and a couple of supplies. Later Mike offered to take his truck down the road for some agua purificada refills. I went along. The rest of the day was taken up mostly by a siesta until the Howler monkeys arrived poolside and circled up close and personal in the trees, very cool, lots of howling as well. Lulu was curious but also fright-ened as were all the other dogs.

Palenque (Spanish pronunciation: [pa’leŋke], Yucatec Maya: Bàak’ /ɓàːkʼ/) was a Maya city state in southern Mexico that flourished in the 7th century. The Palenque ruins date from ca. 226 BC to ca. AD 799. After its decline, it was absorbed into the jungle of cedar, mahogany, and sapodilla trees, but has since has been excavated and restored and is now a famous ar-chaeological site attracting thousands of visitors. It is located near the Usumacinta River in the Mexican state of Chiapas, about 130 km (81 mi) south of Ciudad del Carmen, 150 m (164 yd) above sea level. It averages a humid 26°C (79°F) with roughly 2160 mm (85 in) of rain a year.

Palenque (Spanish pronunciation: [pa’leŋke], Yucatec Maya: Bàak’ /ɓàːkʼ/) was a Maya city state in southern Mexico that flourished in the 7th century. The Palenque ruins date from ca. 226 BC to ca. AD 799. After its decline, it was absorbed into the jungle of cedar, mahogany, and sapodilla trees, but has since has been excavated and restored and is now a famous ar-chaeological site attracting thousands of visitors. It is located near the Usumacinta River in the Mexican state of Chiapas, about 130 km (81 mi) south of Ciudad del Carmen, 150 m (164 yd) above sea level. It averages a humid 26°C (79°F) with roughly 2160 mm (85 in) of rain a year.

Palenque is a medium-sized archeological site, much smaller than such huge sites as Tikal, Chichen Itza, or Copán, but it contains some of the finest architecture, sculpture, roof comb and bas-relief carvings that the Mayas produced. Much of the history of Palenque has been reconstructed from reading the hieroglyphic inscriptions on the many monuments; historians now have a long sequence of the ruling dynasty of Palenque in the 5th century and extensive knowledge of the city-state’s ri-valry with other states such as Calakmul and Toniná. The most famous ruler of Palenque was K’inich Janaab Pakal, or Pacal the Great, whose tomb has been found and excavated in the Tem-ple of the Inscriptions.

Abandonment

During the 8th century, B’aakal came under increasing stress, in concert with most other Classic Mayan city-states and there was no new elite construction in the ceremonial center some-time after 800. An agricultural population continued to live here for a few generations then the site was abandoned and was slowly grown over by the forest. The district was very sparsely populated when the Spanish first arrived in the 1520s. Occa-sionally city-state lords were women. Lady Sak Kuk ruled at Palenque for at least three years starting in 612 CE, before she passed her title to her son. However, these female rulers were accorded male attributes. Thus, these women became more masculine as they assumed roles that were typically male roles.

Modern investigations

Palenque is perhaps the most studied and written-about of Maya sites. After de la Nada’s brief account of the ruins, no at-tention was paid to them until 1773 when one Don Ramón de Ordoñez y Aguilar examined Palenque and sent a report to the Capitán General in Antigua, Guatemala, a further examination was made in 1784 saying that the ruins were of particular interest, so two years later, surveyor and architect Antonio Bernas-coni was sent with a small military force under Colonel Antonio del Río to examine the site in more detail.

Del Rio’s forces smashed through several walls to see what could be found, doing a fair amount of damage to the Palace, while Bernasconi made the first map of the site as well as drawing copies of a few of the bas-relief figures and sculptures. Draughtsman Luciano Castañeda made more drawings in 1807, and a book on Palenque, Descriptions of the Ruins of an An-cient City, discovered near Palenque, was published in London in 1822, based on the reports of those last two expeditions to-gether with engravings based on Bernasconi and Castañeda’s drawings; two more publications in 1834 contained descriptions and drawings based on the same sources.

Juan Galindo visited Palenque in 1831, and filed a report with the Central American government. He was the first to note that the figures depicted in Palenque’s ancient art looked like the local native Americans; some other early explorers, even years later, attributed the site to such distant peoples as Egyptians,

Polynesians, or the Lost Tribes of Israel.

Starting in 1832, Jean Frederic Waldeck spent two years at Palenque making numerous drawings, but most of his work was not published until 1866. Meanwhile the site was visited in 1840 first by Patrick Walker and Herbert Caddy on a mission from the governor of British Honduras, and then by John Lloyd Stephens and Frederick Catherwood who published an illus-trated account the following year which was greatly superior to the previous accounts of the ruins

Claude-Joseph Désiré Charnay took the first photographs of Palenque in 1858, and returned in 1881–1882. Alfred Maudslay encamped at the ruins in 1890–1891 and took extensive photo-graphs of all the art and inscriptions he could find and made paper and plaster molds of many of the inscriptions and de-tailed maps and drawings, setting a high standard for all future investigators to follow. Maudslay learned the technique of mak-ing the papier mache molds of the sculptures from Frenchman

Désiré Charnay.

Several other expeditions visited the ruins before Frans Blom of Tulane University in 1923, who made superior maps of both the main site and various previously-neglected outlying ruins and filed a report for the Mexican government on recommenda-tions on work that could be done to preserve the ruins.

From 1949 through 1952, Alberto Ruz Lhuillier supervised exca-vations and consolidations of the site for Mexico’s National In-stitute of Anthropology and History (INAH); it was Ruz Lhuillier who was the first person to gaze upon Pacal the Great’s tomb in over a thousand years. Ruz worked for four years at the Temple of Inscriptions before unearthing the tomb. Further INAH work was done in lead by Jorge Acosta into the 1970s.

In 1973, the first of the very productive Palenque Mesa Re-donda (Round table) conferences was held here on the inspira-tion of Merle Greene Robertson; thereafter every few years leading Mayanists would meet at Palenque to discuss and ex-amine new findings in the field. Meanwhile Robertson was con-ducting a detailed examination of all art at Palenque, including recording all the traces of color on the sculptures. The 1970s also saw a small museum built at the site.

By 2005, the discovered area covered up to 2.5 km² (1 sq mi), but it is estimated that less than 10% of the total area of the city is explored, leaving more than a thousand struc-tures still covered by jungle.

Submitted by Dan and Lisa Goy

Owners of Baja Amigos RV Caravan Tours

Experiences from our 90-day Mexico RV Tour: January 7-April 5, 2016

www.BajaAmigos.net

Download the full edition or view it online

Dan and Lisa Goy, owners of Baja Amigos RV Caravan Tours, have been making Mexico their second home for more than 30 years and love to introduce Mexico to newcomers.

You must be logged in to post a comment.