By Dan and Lisa Goy from the June 2017 Edition

February 29 – March 5, 2016 (Day 54-59)

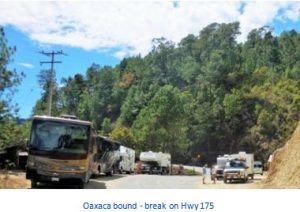

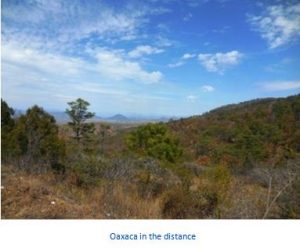

We left Playa Zipolite and Puerto Angel before 8:00 on the last day of February headed for Oaxaca on what  should have normally been a shorter driving day given this was only 269 km or 150 miles away. Lead by Grant and Anita, we were on Hwy 175, within the first hour, on what was nothing less than a spectacular drive.

should have normally been a shorter driving day given this was only 269 km or 150 miles away. Lead by Grant and Anita, we were on Hwy 175, within the first hour, on what was nothing less than a spectacular drive.

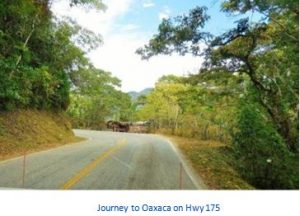

We picked a good time to do this drive as the Sierra Madre del Sur mountains are subject to heavy rainfall during the rainy season in most years. The damage can often be so widespread that the highway is almost always in some state of disrepair. We found the road to be in very good shape, but could see where damage had occurred previously.

Hwy 175 is truly one of the most beautiful highways in the world which winds through the Sierra Madre del Sur. The trip from Puerto Angel to Oaxaca took us a full day, arriving in Oaxaca about 5:30 pm. Traveling north from Hwy 200, the highway ascends rapidly into the mountains, and the climate changes accordingly.

Hwy 175 is truly one of the most beautiful highways in the world which winds through the Sierra Madre del Sur. The trip from Puerto Angel to Oaxaca took us a full day, arriving in Oaxaca about 5:30 pm. Traveling north from Hwy 200, the highway ascends rapidly into the mountains, and the climate changes accordingly.

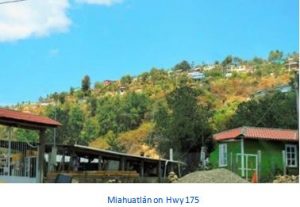

We went from the coast tropics to coffee-growing regions in no time at all. Not hard to see that some people suffer from motion sickness on the highway due to the twisting nature of the road, steep incline and endless switchbacks. We climbed over 2500 meters (8500 feet) before dropping into the valley at Miahuatlán.

Deep divers should bear in mind that driving this highway after diving is equivalent to flying after diving you will reach an altitude of 8000′ within two or three hours, the same altitude to which airline cabins are pressurized.

will reach an altitude of 8000′ within two or three hours, the same altitude to which airline cabins are pressurized.

We really only had one unscheduled delay when Bruce and Marian picked up a bolt just before our lunch break before Miahuatlán. With Grant’s help, and impact gun, they had it changed in no time. This was a very memorable drive, for sure.

All our Baja Amigos have arrived in Oaxaca under sunny skies and warm temperatures, quite a change since the hot steamy weather on the Pacific Coast we left behind. We thought we would arrive at our destination to meet the Amigos Rodante RV Caravan at the  newly-opened Oaxaca Campground and RV Park. As it turned out, their arrival had been delayed and we were free to select our sites. We parked, levelled and had an impromptu Happy Hour and decided that tomorrow the exploring of Oaxaca and surrounding would begin.

newly-opened Oaxaca Campground and RV Park. As it turned out, their arrival had been delayed and we were free to select our sites. We parked, levelled and had an impromptu Happy Hour and decided that tomorrow the exploring of Oaxaca and surrounding would begin.

Our first day out and about, we visited Tule (Santa María del Tule), a town next door to the city of Oaxaca (11 km {6.8 mi}) SE of the city on Highway 190, passing the ruins of Mitla. The town and municipality are named for the patron saint of the place, the Virgin Mary and “Tule” comes from the Náhuatl word “tulle” or “tullin” which means bulrush.

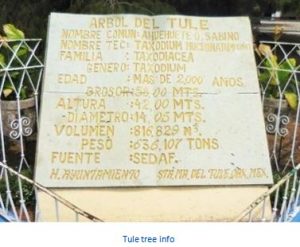

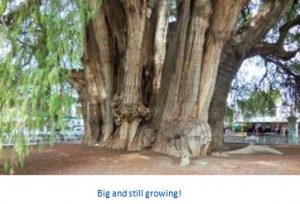

2000 year old tree in Tule, near Oaxaca one of the oldest, largest and widest trees in the world. El Árbol  del Tule (Spanish for The Tree of Tule) is a tree located in the church grounds in the town center of Santa María del Tule in the Mexican state of Oaxaca, approximately 9 km (6 mi) east of the city of Oaxaca on the road to Mitla. It is a Montezuma cypress (Taxodium mucronatum), or ahuehuete (meaning “old man of the water” in Nahuatl). It has the stoutest trunk of any tree in the world. In 2001, it was placed on a UNESCO tentative list of World Heritage Sites. This is well worth a visit, a very impressive site indeed.

del Tule (Spanish for The Tree of Tule) is a tree located in the church grounds in the town center of Santa María del Tule in the Mexican state of Oaxaca, approximately 9 km (6 mi) east of the city of Oaxaca on the road to Mitla. It is a Montezuma cypress (Taxodium mucronatum), or ahuehuete (meaning “old man of the water” in Nahuatl). It has the stoutest trunk of any tree in the world. In 2001, it was placed on a UNESCO tentative list of World Heritage Sites. This is well worth a visit, a very impressive site indeed.

This tree is one of a number of old Montezuma cypress (Taxodium mucronatum) trees that grow in the town. It has an age of at least 2,000 years, with its existence chronicled by both the Aztecs and the Spanish that founded the city of Oaxaca. It has a height of forty meters, a volume of between 700 and 800 m3, an estimated weight of 630 tons and a circumference of about forty meters. The trunk is so wide that thirty people with  arms extended joining hands are needed to encircle it. The tree dwarfs the town’s main church and is taller than its spires, and it is still growing.

arms extended joining hands are needed to encircle it. The tree dwarfs the town’s main church and is taller than its spires, and it is still growing.

The town’s claim to fame is as the home of a 2,000-year-old Montezuma cypress tree, known as El Árbol del Tule, which is the indigenous peoples of this area, the tree was sacred. According to Mixtec myth, people originated from cypress trees, which were considered sacred and a genus. This particular tree was the site of a ritual which included the sacrifice of a dove and was realized for the last time in 1834.

According to Mixe myth, the origin of this particular tree is the walking stick of a god or a king by the name of Conday, who stuck his walking stick, supposedly weighing 62 kilos, into the ground on which he rested. From that point on, the tree began to grow and, according to the king version of the story, the king died the same day the tree began to grow.

same day the tree began to grow.

The tree has gnarled branches and trunk, and various local leg- ends relate what appear to be animals and other shapes growing in the tree. Today, these forms have names such as “the elephant,” “the lion,” “the Three Kings,” “the deer”, “the pineapple,” “the fish,” “the squirrel’s tail” and “Carlos Salinas’ ears.”

Local guides point out the shapes using pocket mirrors to reflect the sun. We also took time to visit the town square and various shops, sampling Mescal, a speciality libation of Oaxaca.

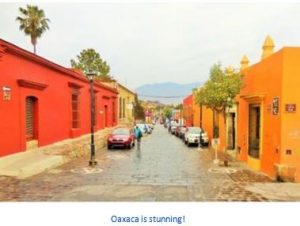

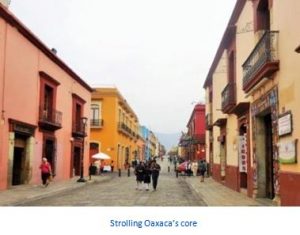

The next day we headed into Oaxaca City and jumped on a local Trolley Bus Tour, both economical and great value, good to get a view of the town for a sense of where we want to visit. The city and municipality of Oaxaca de Juárez, or simply Oaxaca, is the capital and  largest city of the Mexican state of the same name. It is located in the Centro District in the Central Valleys region of the state, on the foothills of the Sierra Madre at the base of the Cerro del Fortín extending to the banks of the Atoyac River.

largest city of the Mexican state of the same name. It is located in the Centro District in the Central Valleys region of the state, on the foothills of the Sierra Madre at the base of the Cerro del Fortín extending to the banks of the Atoyac River.

This city relies heavily on tourism, which is based on its large number of colonialera structures as well as the native Zapotec and Mixtec cultures and archeological sites. It, along with the archeological site of Monte Albán, was named a World Heritage Site in 1987.

It is also the home of the month-long cultural festival called the “Guelaguetza”, which features Oaxacan  dance from the seven regions, music and a beauty pageant for indigenous women. We spent the next 3 days visiting Oaxaca, shopping at markets, visiting various historical sites, trying out different restaurants and lots of walking. We plan on spending many more in Oaxaca when we return.

dance from the seven regions, music and a beauty pageant for indigenous women. We spent the next 3 days visiting Oaxaca, shopping at markets, visiting various historical sites, trying out different restaurants and lots of walking. We plan on spending many more in Oaxaca when we return.

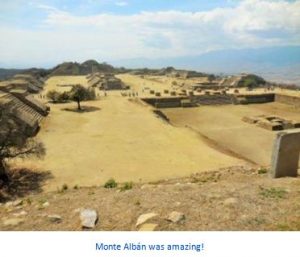

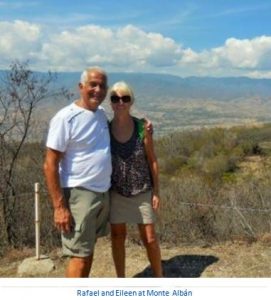

Monte Albán was amazing!

The last day of our Oaxaca visit, we headed for Monte Albán, a pre Hispanic city that was an ancient capital of the Zapotecs. It reached its peak between 500 BCE and 800 CE with about 35,000 inhabitants. Monte Albán is known for its architecture, its carved stones and the ceramic urns.

The partially excavated civic ceremonial center of the Monte Albán site is situated atop an artificially leveled ridge which, with an elevation of about 1,940 m (6,400 ft) above mean sea level rises some 400 m (1,300 ft) from the valley floor, in an easily-defensible location.

The partially excavated civic ceremonial center of the Monte Albán site is situated atop an artificially leveled ridge which, with an elevation of about 1,940 m (6,400 ft) above mean sea level rises some 400 m (1,300 ft) from the valley floor, in an easily-defensible location.

The site is characterized by several hundred artificial terraces, and a dozen clusters of mounded architecture covering the entire ridgeline and surrounding flanks. The archaeological ruins on the nearby Atzompa and El Gallo hills to the north are traditionally considered to be an integral part of the ancient city as well. Besides being one of the earliest cities of Mesoamerica, Monte Albán’s importance stems also from its role as the preeminent Zapotec socio political and economic center for close to a thousand years. Founded toward the end of the Middle Formative period at around 500 BC, by the Terminal Formative era (ca.100 BCE-CE 200), Monte Albán had become the capital of a large-scale expansionist polity that dominated much of the Oaxacan highlands and interacted with other Mesoamerican regional states such as Teotihuacan to the north. The city had lost its political preeminence by the end of the Late Classic (ca. CE 500-750) and soon thereafter was largely abandoned.

expansionist polity that dominated much of the Oaxacan highlands and interacted with other Mesoamerican regional states such as Teotihuacan to the north. The city had lost its political preeminence by the end of the Late Classic (ca. CE 500-750) and soon thereafter was largely abandoned.

Small-scale reoccupation, opportunistic reutilization of earlier structures and tombs, and ritual visitations marked the archaeological history of the site into the Colonial period. We spent an entire day walking around the site and visiting the museum on site. If you are visiting Oaxaca, make sure you make time to visit this archeological site.

History of Oaxaca

There had been Zapotec and Mixtec settlements in the valley of Oaxaca for thousands of years, especially in connection with the important ancient centers of Monte Albán and Mitla, which are close to modern Oaxaca City. The Aztecs entered the valley in 1440 and named it “Huaxyacac,” a Nahuatl phrase meaning “among the huaje” (Leucaena leucocephala) trees.

There had been Zapotec and Mixtec settlements in the valley of Oaxaca for thousands of years, especially in connection with the important ancient centers of Monte Albán and Mitla, which are close to modern Oaxaca City. The Aztecs entered the valley in 1440 and named it “Huaxyacac,” a Nahuatl phrase meaning “among the huaje” (Leucaena leucocephala) trees.

A strategic military position was created here, at what is now called the Cerro (large hill) del Fortín to keep an eye on the Zapotec capital of Zaachila and secure the trade route between the Valley of Mexico, Tehuantepec and what is now Central America. When the Spanish arrived in 1521, the Zapotecs and the Mixtecs were involved in one of their many wars. Spanish conquest would ultimately end the conflict.

The first Spanish expedition here arrived late in 1521, headed by Captain Francisco de Orozco, and accompanied by 400 Aztecs. Hernán Cortés sent Francisco de Orozco to Oaxaca be- cause Moctezuma II said that the Aztec’s gold came from there .

.

The Spanish expedition under Orozco set about building a Spanish city where the Aztec military post was at the base of the Cerro de Fortín. The first mass was said here by Chaplain Juan Díaz on the bank of the Atoyac River under a large huaje tree, where the Church of San Juan de Dios would be con-

structed later. This same chaplain added saints’ names to the surrounding villages in addition to keeping their Nahuatl names: Santa María Oaxaca, San Martín Mexicapan, San Juan Chapultepec, Santo Tomás Xochimilco, San Matías Jalatlaco, Santiago Tepeaca, etc.

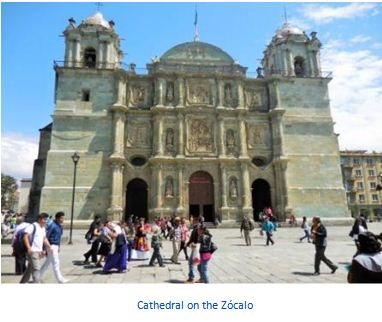

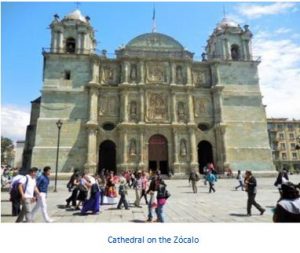

This group of Spaniards chose their first mayor, Gutiérrez de Badajoz, their first town council and began  construction of the cathedral of Oaxaca in 1522. Their name for the settlement was Guajaca, a Hispanization of the Nahuatl name (which would later be respelled as Oaxaca).

construction of the cathedral of Oaxaca in 1522. Their name for the settlement was Guajaca, a Hispanization of the Nahuatl name (which would later be respelled as Oaxaca).

The establishment of the relatively independent village was not favoured by Hernán Cortés, who wanted power over the entire region for himself. Cortés sent Pedro de Alvarado who pro- ceeded to drive out most of the village’s population.

The original Spanish settlers appealed to the Spanish crown to recognize the village they founded, which it did in 1526, with land divided among the Spaniards of Orozco’s expedition. However, this did not stop Cortés from driving out the population of the village once again and replacing the town council only three months after royal recognition.

Once again, the original founders appealed to Spanish royal authority, this time to the viceroy in Mexico City, Nuño de Guzmán. This viceroy also sided with the original founders, and the town was re-founded in 1529 as Antequera, in honor of Nuño de Guzmán’s hometown. Francisco de Herrera convened the new, Crown- approved town council, and the first layout of the settlement was mapped out by Juan Peláez de Berrio.

approved town council, and the first layout of the settlement was mapped out by Juan Peláez de Berrio.

In the meantime, Cortés was able to obtain from the crown the title of the Marquis of the Valley of Oaxaca, which contains the disputed village. This permitted him to tax the area heavily, and to have control of the territory that surrounded the village. The village was then in a position of having to survive surrounded by villages which answered to Cortés.

These villages not only did not take orders from Antequera, they were hostile to it, mostly likely encouraged by Cortés. To counter this, the village petitioned the Crown to be elevated to the status of a city, which would give it certain rights, privileges and exceptions. It would also ensure that the settlement would remain under the direct control of the king, rather than of Cortés. This petition was granted in 1532 by Charles V of Spain.

After the Independence of Mexico in 1821, the city became the seat of a municipality, and both the name of the city and the municipality became Oaxaca, changed from Antequera. In 1872, “de Juárez” was added to the city and municipality names to honor Benito Juárez, who began his legal and political career here. We visited Casa Juárez with our time in Oaxaca city.

Where to go, what to see

The city centre was included as a World Heritage Site designated by UNESCO, in recognition of its treasure of historic buildings and monuments. Fortunately, we were able to visit many of these.

The city centre was included as a World Heritage Site designated by UNESCO, in recognition of its treasure of historic buildings and monuments. Fortunately, we were able to visit many of these.

The Plaza de la Constitución, or Zócalo, was planned out in 1529 by Juan Peláez de Berrio. During the entire colonial period, this plaza was never paved, nor had sidewalks, only a marble fountain that was placed here in 1739. This was removed in 1857 to put in the kiosk and trees were planted.

In 1881, the vegetation here was rearranged and, in 1885, a statue of Benito Juárez was added. It was remodeled again in 1901 and a new Art Nouveau kiosk installed. Fountains of green stone with capricious figures were installed in 1967. The kiosk in the center hosts the State Musical Band, La Marimba and other groups.

The plaza is surrounded by various portals. On the south side of the plaza are the Portales de Ex- Palacio de Gobierno, which was vacated by the government in 2005 and then re- opened as a museum called “Museo del Palacio ‘Espacio de Diversidad.” Other portals include the “Portal de Mercadores”

Palacio de Gobierno, which was vacated by the government in 2005 and then re- opened as a museum called “Museo del Palacio ‘Espacio de Diversidad.” Other portals include the “Portal de Mercadores”

on the eastern side, “Portal de Claverias” on the north side and the “Portal del Señor” on the west side.

The State Government Palace is located on the main square of Oaxaca City. This site used to be the Portal de la Alhóndiga (warehouse) and in front of the palace is the Benito Juárez Market. The original palace was inaugurated in 1728, on the wedding day of the prince and princess of Spain and Portugal. The architectural style was Gothic.

The building currently on this site was begun in 1832, inaugurated in 1870 but was not completed until 1887. The inside contains murals reflecting Oaxaca’s history from the pre Hispanic era, the colonial era and post-Independence. Most of these were painted by Arturo Garcia Bustos in the 1980s.

The building currently on this site was begun in 1832, inaugurated in 1870 but was not completed until 1887. The inside contains murals reflecting Oaxaca’s history from the pre Hispanic era, the colonial era and post-Independence. Most of these were painted by Arturo Garcia Bustos in the 1980s.

The Federal Palace is located across from the Cathedral and used to be the site of the old Archbishop’s Palace until 1902. Its architecture is “neo Mixtec” reflecting the nationalism of the early 20th century and the reverence in which the Mixtec- Zapotec culture has been held in more recent times. The architectural elements copy a number of those from Mitla and Monte Albán

Northwest of the Zócalo is the Alameda de León, a garden area that is essentially an annex of the main square. In 1576, Viceroy Martín Enríquez de Almanza set aside two city blocks on which to build the city government offices, but they were never built here. One of the blocks was sold and the other be- came a market.

Submitted by Dan and Lisa Goy

Owners of Baja Amigos RV Caravan Tours

Experiences from our 90-day Mexico RV Tour: January 7-April 5, 2016 www.BajaAmigos.net

Download the full edition or view it online

Dan and Lisa Goy, owners of Baja Amigos RV Caravan Tours, have been making Mexico their second home for more than 30 years and love to introduce Mexico to newcomers.