By Kirby Vickery from the July 2018 Edition

I have found the Aztec people to have been very intelligent and industrious to take over the Mixtec world through tribal consolidation, then concur as they did, although their empire was built on existing platforms previously established by the Mayan and Olmec.

Because of their priest class’ absolute rule and demands made of them by their gods, the Aztecs had developed a quest for

the reason why everything that was – was. Their pantheon of gods gave reason for everything in their world. Not only in the physical, but well into the abstract worlds of feeling, emotion, and perception of beauty and grace as well into the darker sides of things such as illness, darkness, and death.

Most people interested in Aztec mythology are aware of most of these gods that all played major roles in the Aztec five worlds of creation. To this list, the Aztec had many others, to include a whole group of minor deities, one of whom I’ll talk about later. At the far end of this line of mythological beings where a bunch of demons. Here are a few:

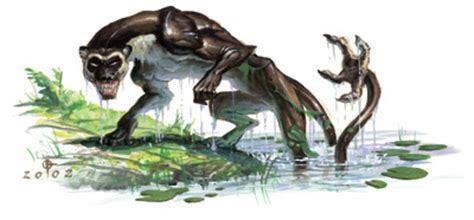

THE AHUIZOTL

The Ahuizotl is an otter-like cryptid from Mexico. The Ahuizotl is described as a dog-sized otter that has a human-like hand on its tail.

The Ahuizotl hides underwater in the lake of Texcoco. It sticks the hand on the back of its tail out of the water and makes a sound similar to that of a crying baby which draws a person to go in the water to save the baby. Once its victim is in the water, the Ahuizotl drags the person underwater, drowns them and rips out the victim’s teeth, fingernails, and eyeballs and then proceeds to eat those parts because it’s said that it likes the crunchy parts of its victims the most. Experts say that the Ahuizotl could have existed at one point in the past as an ancient relative to the otter.

Personally, I feel sightings of such beasts were actually of crocodiles or alligators attacking something or someone while being seen from a distance. Both these animals have a tendency to clamp on and roll their victims down into the water to drown them. It is very violent and quick.

ITZPAPALOTL was the obsidian butterfly and mother of the Titzimime demons.

The Titzimime were demons who could be owned by the gods and apparently act as messengers and could also carry out tasks for their owners. Mexico being volcanic, the Aztecs loved the volcanic glass, otherwise known as obsidian, whose beauty climbs right up there with butterflies when worked properly. That is the tie in with the Titzimime even through the deception: The Titzimime (“monsters descending from above”) were celestial demons in Aztec mythology that continuously threaten to destroy the world. They are said to be the stars that battle the sun each dusk and dawn. One story from the ‘Histoyre du Mechique’ describes the wraith of the Titzimime. Mayahuel was the goddess of maguey who lived with her grandmother, a Titzimime, in the sky.

The Titzimime were demons who could be owned by the gods and apparently act as messengers and could also carry out tasks for their owners. Mexico being volcanic, the Aztecs loved the volcanic glass, otherwise known as obsidian, whose beauty climbs right up there with butterflies when worked properly. That is the tie in with the Titzimime even through the deception: The Titzimime (“monsters descending from above”) were celestial demons in Aztec mythology that continuously threaten to destroy the world. They are said to be the stars that battle the sun each dusk and dawn. One story from the ‘Histoyre du Mechique’ describes the wraith of the Titzimime. Mayahuel was the goddess of maguey who lived with her grandmother, a Titzimime, in the sky.

One time, Quetzalcoatl convinced her to descend to earth with him and join with him into a forked tree with Quetzalcoatl as one branch and Mayahuel as the other. When Mayahuel’s grandmother awakens and finds her missing, she summons other Titzimime to find her granddaughter. They descend to earth, and just as they arrive, the tree that Quetzalcoatl and Mayahuel had hidden as splits in two. Recognizing her grand-mother as one of the branches, she tears it apart and passes coyotes were an Aztec symbol of astuteness and worldly-wisdom, pragmatism and male beauty and youthfulness.

Huehuecóyotl the remains of Mayahuel to the other Titzimime to devour, leaving the branch that Quetzalcoatl disguised himself as fully intact. After they had left, Quetzalcoatl gathered up the Maya-huel’s bones and buried them, and from that grave, the first maguey plant grew. (Maguery was the source of an alcoholic beverage that was important in Aztec ceremonies as both a rit-ual drink and a sacrificial offering.)

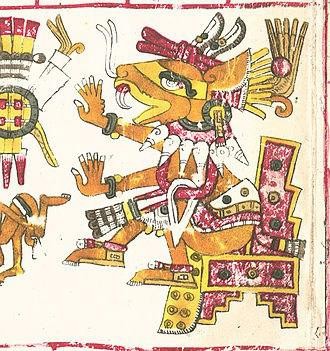

HUEHUECÓYOTL

Huehuecóyotl, the Old Coyote is the Teotl (God) of dance, song, and mischief; he is the trickster who leads men astray. He rules over the day sign “Lizard” and the Trecena “Flower.” He is a patron of liars, male sexuality, good luck, story-telling, and hedonism. He appears as a coyote, with human hands and feet.

In Aztec mythology, Huehuecóyotl is the auspicious god of mu-sic, dance, mischief and song of Pre-Columbian Mexico. He is the patron of uninhibited sexuality and rules over the day sign in the Aztec calendar named Cuetzpalin (lizard) and the fourth trecena Xochitl (“flower” in Nahuatl). He is depicted in the Codex Borbonicus as a dancing coyote with human hands and feet, accompanied by a human drummer. The name “very old coyote” conveyed positive meanings for the Aztec populace;coyotes were an Aztec symbol of astuteness and worldly-wisdom, pragmatism and male beauty and youthfulness.

The prefix “huehue”, which in Nahuatl means “very old”, was attached to gods in Aztec mythology that were revered for their old age, wisdom, philosophical insights and connections to the divine. Although often appearing in stories as male,

Huehuecóyotl can be gender changing, as is the case of many of the offspring of Tezcatlipoca. He can be associated with indulgence, male sexuality, good luck and story telling. One of his prominent female lovers was Temazcalteci (also Temaxcal techi), the goddess of bathing and sweat baths (temazcalli), also known as Mexican sauna and Xochiquetzal, the goddess of love, beauty, female sexuality, prostitutes, flowers and young mothers.

As all Aztec deities, Huehuecóyotl was dualistic in his exercise of good and evil. He was perceived as a balanced god; depictions of his dark side include a coyote appearance (non-human) with black or yellow feathers, as opposed to the customary green feathers.

In most depictions of Huehuecóyotl, he is followed by a human drummer, or groups of humans that appear to be friendly to him (as opposed to worshipping), which is exceptional in Mesoamerican culture.

Stories derived from the Codex Telleriano Remensis make him a benign prankster, whose tricks are often played on other gods or even humans but tended to backfire and cause more trouble for himself than for the intended victims. A great partygiver, he also was alleged to foment wars between humans to relieve his boredom. He is a part of the Tezcatlipoca (Smoky Mirror) family of the Mexica gods, and has their shape shifting powers.

Those who had indications of evil fates from other gods would sometimes appeal to Huehuecóyotl to mitigate or reverse their fate. Huehuecóyotl shares many characteristics with the trickster Coyote of the North American tribes, including storytelling and choral singing.

The fourth day of the thirteen-day Mexican week belonged to Huehuecóyotl. He was the only friend to Xolotl who is the god of twins, sickness and deformity and accompanies the dead to Mictlan (the underworld of Aztec mythology). Their association is born from the canine nature of both gods.

Among the many colorful gods of the Aztec empire, Huehuecóyotl or Old Man Coyote (Huehue =old man), was a shape-shifting god of merriment and magic and sexual energy.

Although he was an incorrigible trickster, often playing pranks that could turn cruel, he bestowed special gifts of song, dance, stories, and poetry. In the Coyote Kiva, Huehuecoyotl is celebrated as the icon of poets, the Ancient Voice that speaks for those in silence, the Spirit Voice that wails for justice in a broken world, the Sacred Belly Voice that roars with laughter at human folly, and the Embracing Voice that whispers love songs to the night.

Here we find Huehuecóyotl’s sons and daughters, speaking in all his brightness and darkness, his sorrow, joy, wisdom, and truth. Poets from all over the world contribute to this seat in the kiva. Their works are presented according to topic.

The importance of Aztec music in the lives of the citizens of the empire is hinted at in this quote from Spanish friar Gerónimo de Mendieta:

“Each lord had in his house a chapel with composer singers of dances and songs, and these were thought to be ingenious in knowing how to compose the songs in their manner of meter and the couplets that they had. Ordinarily they sang and danced in the principal festivities that were every twenty days, and also on other less principal occasions…”

When a child was sent to school, music and the playing of instruments was an important subject to be learned. Students between 12 and 15 would learn songs that were important in their culture. And, as we see in the quote above, music was important enough that the nobles often had their own band,song writers and studio right at home. Elders in the home would teach children the songs they needed to know.

Aztec music was a constant and important part of life. Not only was music used for enjoyment, it was a way of passing on culture, of sharing an understanding of religion, of making an emotional connection with the events of life.

Download the full edition or view it online

—

Kirby was born in a little burg just south of El Paso, Texas called Fabens. As he understand it, they we were passing through. His history reads like a road atlas. By the time he started school, he had lived in five places in two states. By the time he started high school, that list went to five states, four countries on three continents. Then he joined the Air Force after high school and one year of college and spent 23 years stationed in eleven or twelve places and traveled all over the place doing administrative, security, and electronic things. His final stay was being in charge of Air Force Recruiting in San Diego, Imperial, and Yuma counties. Upon retirement he went back to New England as a Quality Assurance Manager in electronics manufacturing before he was moved to Production Manager for the company’s Mexico operations. He moved to the Phoenix area and finally got his education and ended up teaching. He parted with the university and moved to Whidbey Island, Washington where he was introduced to Manzanillo, Mexico. It was there that he started to publish his monthly article for the Manzanillo Sun. He currently reside in Coupeville, WA, Edmonton, AB, and Manzanillo, Colima, Mexico, depending on whose having what medical problems and the time of year. His time is spent dieting, writing his second book, various articles and short stories, and sightseeing Canada, although that seems to be limited in the winter up there.