By Kirby Vickery on the November 2019 Edition

To use the word, ‘witchcraft’ with any of the Mesoamerican cultures could almost be called a misnomer. Witchcraft, by its nature and conceptual origins, is purely Old World. The meaning of the word is so broad-based that to try to fit it into a single category of Mesoamerican belief or practice is next to impossible.

The concept of having a separate ‘occult’ just didn’t exist as it does in Western Civilizations based on the Judeo Christian and Muslim religions

Further distinctions in the concepts of the different aspects of witchcraft are: dragons, other mythical occult-generated beasts, simple and complex magic and all the stuff that fits into a Harry Potter movie, ‘Phychomania’ or The Blood Farmers (Hollywood-generated horror movies portraying the occult).

What I was able to find on this subject within the Mesoamerican history was very surprising and so much more than I was able to put into this article.

There were (and still are) very negative and downright scary aspects of witchcraft and sorcery, or ‘Brujería’ (as it is known in Latin America) within the Aztec, Toltec, Maya and other ancient Mesoamerican cultures. But, the important thing to remember is, that this sorcery wasn’t outside the religion as it is in, say, Puritanism or even today’s Catholicism.

It was all built into the inner structures, starting with their creation mythologies and their religions, as practiced by the ancient priests and today’s Shamans in the area.

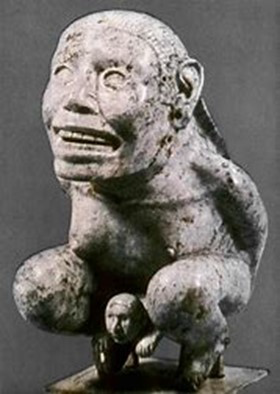

Within the Classic Maya times was one group of supernatural beings (god-like) which fit the concept of witchcraft. Known as Wahy, they were often depicted as animals in the form of a bat, monkey, dog, jaguar, toad or rodent holding plates of severed hands, feet and other body parts. These beings were thought to represent companion spirits or ‘coessences’ which were personification of diseases.

An example of a god or god-like creature in Aztec mythology would be, Tlazolteotl (or Tlaçolteotl,) the goddess of purification, steam bath, midwives, filth and a patroness of adulterers. In Nahuatl, the word tlazolli can refer to vice and diseases. Thus, Tlazolteotl was a goddess of filth (sin), vice, and sexual misdeeds. She was a purification goddess as well, who forgave the sins and disease of those caused by misdeeds, particularly sexual misdeeds.

Her dual nature is seen in her epithets; Tlaelquani (‘she who eats filth [sin]’) and Tlazolmiquiztli (‘the death caused by lust’), and Ixcuina or Ixcuinan (‘she of two faces’). Under the designation of Ixcuinan, she was thought to be plural in number and four sisters of different ages by the names; Tiacapan (the first born), Teicu (the younger sister), Tlaco (the middle sister) and Xocotzin (the youngest sister).

Her son was Centeotl also known as Toci. He presides over the 13th trecena of the sacred 260-day year. Another son was Yum-Kax, the Maya maize god.

The good sorcerer [is] a caretaker, a wise man, a counselor, a person of trust serious, respected, revered, dignified, unri-valed, not subject to insults, a man of discretion, a guardian. Astute, he is keen, careful, helpful; he never harms anyone. The bad sorcerer [is] a doer [of evil], an enchanter. He bewitches women; he deranges, deludes people; he casts spells over them; he charms them; he enchants them; he causes them to be possessed. He deceives people; he confounds them’ (Sahagún 1953–1982, bk. 4:31).

The ‘arch sorcerer’ of the late postclassic period, for example, was Tezcatlipoca, ‘Lord of the Smoking Mirror’. He was never without this main divinatory accoutrement, from which his name derived. He was a bringer of disease and pestilence. However, when prayed to, he could be pleased, and the people would avoid these things. He is a perfect example of how Nahua world view works. He is dangerous and destructive, benevolent and caring all at the same time.

In ancient and contemporary Mesoamerica, the daily struggle is not based on any Judeo Christian concept of good and evil but, instead, is based on one of order and chaos. One such manifestation of this chaos appears as malevolent polluting winds known as ejecame (s. ejecat) that can disrupt rituals and cause disease. These are among many colonial and contemporary Nahua and Maya references to wind-related ailments and afflictions.

In a translated story [Codex], “it was Moctezuma (the guy that handed the Aztec empire over to Cortez because he thought Cortez was a god) who ordered that all the wizards and magicians who could be found in all the provinces be brought before him. Sixty sorcerers were then rounded up; they were old men, wise in the arts of magic. The king instructed them thus: “O elders, my fathers, I am determined to seek the land that has given birth to the Aztec people […] Therefore, prepare to go seek this place in the best way you can and as soon as possible.”

Laden with rich gifts, the sixty sorcerers departed and, sometime later, reached a hill called Coatepec in the province of Tu-la. There they traced magical symbols on the ground, invoked the demon, and smeared themselves with certain ointments that they used and that wizards still use nowadays for there are still great magicians, men who are possessed, among them.

One might ask, how are they not exposed? It is because they conceal one another and hide from us more than any other people on earth.

They have no confidence in the Spaniards and thus it is that these fiendish acts are hidden from us and kept in secret by them; and when, by chance, some magical practice is discovered, if it happens to come to our ears, there is always someone to cover for the sorcerer and keep him silent.

“So it is that upon the hill they invoked the Evil Spirit and begged him to show them the home of their ancestors. The devil, conjured by these spells and pleas, turned some of them into birds and others into wild beasts such as ocelots, jaguars, jackals and wildcats, and took them, together with their gifts, to the land of their forebearers.”

That account is pretty much par for the course in terms of his-torical descriptions of “sorcerers”. There’s clearly some historical basis for this description, as the transformation of a ‘Nahualli’ into his animal form is a distinctly Mesoamerican magical practice.

I would say that the entire Mesoamerican world held their ‘occult’ to a stratified existence ranging from evil gods, down through spirits, to shamans and finally to gnome-like creatures.

To them it was all real, official and not two-sided (good versus evil), as was introduced from the old world.

The full edition or view it online

—

Kirby was born in a little burg just south of El Paso, Texas called Fabens. As he understand it, they we were passing through. His history reads like a road atlas. By the time he started school, he had lived in five places in two states. By the time he started high school, that list went to five states, four countries on three continents. Then he joined the Air Force after high school and one year of college and spent 23 years stationed in eleven or twelve places and traveled all over the place doing administrative, security, and electronic things. His final stay was being in charge of Air Force Recruiting in San Diego, Imperial, and Yuma counties. Upon retirement he went back to New England as a Quality Assurance Manager in electronics manufacturing before he was moved to Production Manager for the company’s Mexico operations. He moved to the Phoenix area and finally got his education and ended up teaching. He parted with the university and moved to Whidbey Island, Washington where he was introduced to Manzanillo, Mexico. It was there that he started to publish his monthly article for the Manzanillo Sun. He currently reside in Coupeville, WA, Edmonton, AB, and Manzanillo, Colima, Mexico, depending on whose having what medical problems and the time of year. His time is spent dieting, writing his second book, various articles and short stories, and sightseeing Canada, although that seems to be limited in the winter up there.