By Dan and Lisa Goy from the April 2017 Edition

Uxmal, Yucatán January 24 and 25 Day 18 and 19

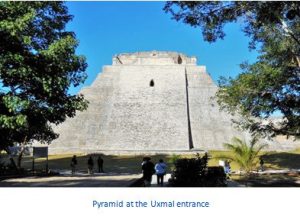

This ancient Maya city is considered one of the most important archaeological sites of Maya culture, along with Chichén Itzá in Mexico; Caracol and Xunantunich in Belize and Tikal in Guatemala. We were able to dry camp on a grass parking lot at the entrance to this ruin and have access to the hotel pool, restaurant and wifi. Uxmal has been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in recognition of its significance.

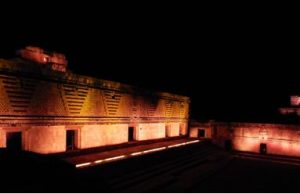

Maya chronicles say that Uxmal was founded about 500 A.D. although most of the city’s major construction took place while Uxmal was the capital of a Late Classic Maya state around 850- 925 AD. After about 1000 AD, Toltec invaders took over, and most building ceased by 1100 AD. Early colonial documents suggest that Uxmal was still an inhabited place of some importance into the 1550s however since Spanish did not build a town here, Uxmal was soon abandoned. Our group hired a great local guide to see this Mayan ruin who was both infor- mative and humorous. Later we went to the light show in the evening, not so impressive.

January 24-26, 2016: Day 18 – 20 – Uxmal 169 km/105 m – 3 hrs

With Grant and Anita in the lead, we said goodbye to Cam- peche and headed out for the Mayan archeological site Uxmal, in the state of Yucatán. Uxmal, founded about 500 AD, was still in use when Cortez arrived in 1518. This was a relatively short and scenic Sunday drive on Highway 261 (169 km/105 miles), on a very quiet Hwy 261 where we were passed by only one bus on a good road. Once we crossed over into the state of Yucatán, the road got even better, sometimes a little narrow, but us Baja drivers are used to narrow roads.

With Grant and Anita in the lead, we said goodbye to Cam- peche and headed out for the Mayan archeological site Uxmal, in the state of Yucatán. Uxmal, founded about 500 AD, was still in use when Cortez arrived in 1518. This was a relatively short and scenic Sunday drive on Highway 261 (169 km/105 miles), on a very quiet Hwy 261 where we were passed by only one bus on a good road. Once we crossed over into the state of Yucatán, the road got even better, sometimes a little narrow, but us Baja drivers are used to narrow roads.

We arrived at Uxmal just after noon and parked on a field on the right of the site entrance, paying $131  pesos per RV, per night, including internet and, for another $50 pesos, you could use the pool at the adjacent hotel. Certainly cannot complain about that.

pesos per RV, per night, including internet and, for another $50 pesos, you could use the pool at the adjacent hotel. Certainly cannot complain about that.

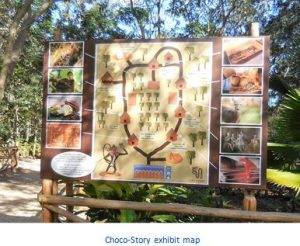

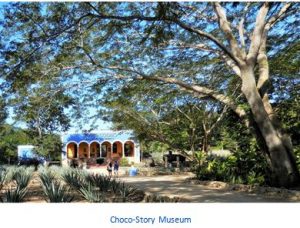

After lunch, we headed across the highway to a Choco-Story Museo as coco beans were highly valued and traded in the Mayan world. The museum, arranged as a series of traditional thatched-roof houses presenting different themes, focuses as much on cocoa’s mystical significance to the Maya as on the confection itself.

The stone that links the huts winds through a veritable botanical garden, with signs explaining the importance of such plants as henequen (sisal), pomegranate, habanero pepper, tamarind, lime, guava and,  of course the cacao tree. Cacao is rarely grown in the Yucatán today because of the thin, rocky soil, but the Puuc region one of the very few places where you’ll encounter anything resembling a hill has deeper soil covering the lime- stone shelf that forms the peninsula, as well as higher rainfall than in the coastal areas. We found that the Choco-Story Mex- ico location at Uxmal is really fantastic in that it brings to life the Mayan culture and the ancient Mayans’ reverence for cacao as being a sacred food. We also enjoyed the Mayan ceremony at the Choco-story Museo that paid tribute to cacao.

of course the cacao tree. Cacao is rarely grown in the Yucatán today because of the thin, rocky soil, but the Puuc region one of the very few places where you’ll encounter anything resembling a hill has deeper soil covering the lime- stone shelf that forms the peninsula, as well as higher rainfall than in the coastal areas. We found that the Choco-Story Mex- ico location at Uxmal is really fantastic in that it brings to life the Mayan culture and the ancient Mayans’ reverence for cacao as being a sacred food. We also enjoyed the Mayan ceremony at the Choco-story Museo that paid tribute to cacao.

We spent most of the afternoon exploring the historic choco- late-making equipment and paraphernalia on-site, enjoying the ecopark and the featured flora and fauna, shopping in the chocolate and gift shop, and taking part in some of the hands

on classes the Choco Story Museum that Uxmal has to offer.

Every chocolate lover who visits Mérida or Uxmal should make their way to the Choco-Story Museum to gain a greater understanding of the world of chocolate and Mexico’s deep connection to it. Apparently, there are other Choco-Story Museums in Brussels, Belgium, as well as Paris and Prague.

To the Maya, the addictive elixir was far more than a mood elevator or a PMS antidote. Without benefit of medical journals extolling chocolate’s antioxidant and endorphin-boosting virtues, they did indeed use it to treat everything from fatigue to kidney stones to impotence. But it was also a form of currency you could buy a rabbit for 10 cocoa beans, while a strong, healthy slave would set you back 100 beans. Cocoa was still used as money during the Spanish conquest. Perhaps most  important to the ancients, chocolate was the “Food of the Gods” and was used in spiritual ceremonies, sometimes tinted with the red annatto seed (the ground form of which is achiote, a spice still widely used today) to replace blood in sacrificial rites. That evening, we attended the Uxmal light show.

important to the ancients, chocolate was the “Food of the Gods” and was used in spiritual ceremonies, sometimes tinted with the red annatto seed (the ground form of which is achiote, a spice still widely used today) to replace blood in sacrificial rites. That evening, we attended the Uxmal light show.

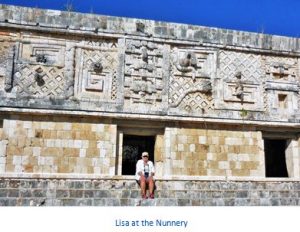

After the Campeche experience, we were excited to see what the archeological site had in store for us. There were many in attendance as darkness fell on the Nunnery Quadrangle (Government Palace). All the seating was arranged on the high- est building overlooking the rectangle opening. It was very loud, 100% in Spanish, and really had only a variety of coloured lights which made the various parts of the site, blue, red green and a couple of colours. At the same time, a narrative of the history of the Mayan people and the subsequent conquest was read, much as you would read out loud to a group of children. This was somewhat disappointing compared to the laser light show that we had seen at the Campeche Zócalo.

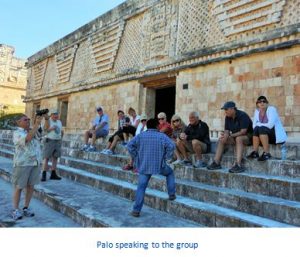

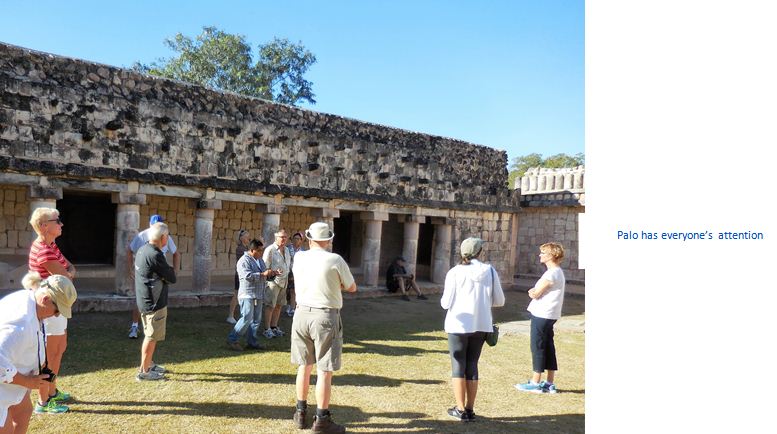

Day 2 at Uxmal and the gang started at 8 am for a tour of then Mayan site with Palo as our guide. $200  pesos and 2 hours later, we were much more informed about this Mayan civilization and the general history of the Mayan culture. Palo was an excellent guide and I would recommend him to anyone. Later the gals decided to make it a poolside afternoon and they had fun for sure. A few of the guys joined them later, had a couple of beers and even some margaritas were consumed.

pesos and 2 hours later, we were much more informed about this Mayan civilization and the general history of the Mayan culture. Palo was an excellent guide and I would recommend him to anyone. Later the gals decided to make it a poolside afternoon and they had fun for sure. A few of the guys joined them later, had a couple of beers and even some margaritas were consumed.

Before dinner, Arturo the site guide manager, dropped by for some conversation about Mexico and the region. A few of us went for dinner at the hotel restaurant, a little pricey but what else would you expect at a tourist location like this? Uxmal was great 2-night stop. The group was up and ready to go the fol- lowing day at the crack of 9 am, headed to Merida, the capital city of the Yucatán State.

Uxmal, the Archeological Site

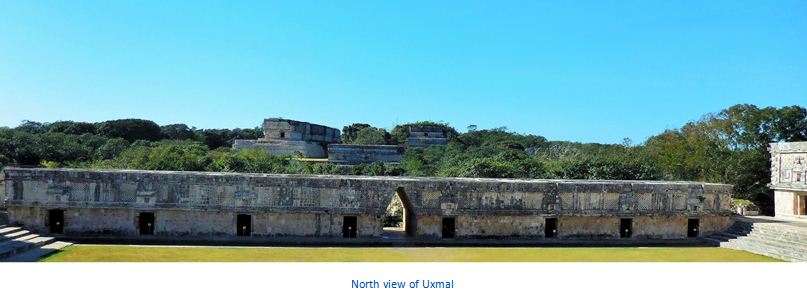

Uxmal (Yucatec Maya: Óoxmáal [óˑʃmáˑl]) is an ancient Maya city of the classical period in present-day Mexico. It is considered one of the most important archaeological sites of Maya culture, along with Chichén Itzá in Mexico; Caracol and Xunantunich in Belize, and Tikal in Guatemala. It is located in the Puuc region and is considered one of the Maya cities most rep- resentative of the region’s dominant architectural style. It has been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in recognition of its significance.

Uxmal (Yucatec Maya: Óoxmáal [óˑʃmáˑl]) is an ancient Maya city of the classical period in present-day Mexico. It is considered one of the most important archaeological sites of Maya culture, along with Chichén Itzá in Mexico; Caracol and Xunantunich in Belize, and Tikal in Guatemala. It is located in the Puuc region and is considered one of the Maya cities most rep- resentative of the region’s dominant architectural style. It has been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in recognition of its significance.

Located 62 km (40 m) south of Mérida, capital of Yucatán state in Mexico, its buildings are noted for their size and decoration. Ancient roads called sacbes connect the buildings, and also were built to other cities in the area such as Chichén Itzá, Caracol and Xunantunich in modernday Belize, and Tikal in modern day Guatemala. These structures are typical of the Riley Kand Puuc style, with smooth low walls that open  on ornate friezes based on representations of typical Maya huts. These are represented by columns (representing the reeds used for the walls of the huts) and trapezoidal shapes (representing the thatched roofs). Entwined snakes and, in many cases two-headed snakes are used for masks of the rain god, Chaac; its big noses represent the rays of the storms.

on ornate friezes based on representations of typical Maya huts. These are represented by columns (representing the reeds used for the walls of the huts) and trapezoidal shapes (representing the thatched roofs). Entwined snakes and, in many cases two-headed snakes are used for masks of the rain god, Chaac; its big noses represent the rays of the storms.

Feathered serpents with open fangs are shown leaving from the same human beings. Also seen in some cities are the influences of the Nahua, who followed the cult of Quetzalcoatl and Tlaloc. These were integrated with the original elements of the Puuc tradition. The buildings take advantage of the terrain to gain height and acquire important volumes, including the Pyramid of the Magician, with five levels, and the Governor’s Palace, which covers an area of more than 1,200 m2 (12,917 sq ft).

Ancient history of Uxmal

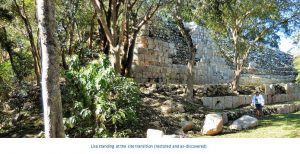

While much work has been done at the popular tourist destination of Uxmal to consolidate and restore buildings, little in the way of serious archeological excavation and research has been done. The city’s dates of occupation are unknown and the estimated population (about 15,000 people) is only a rough guess. Most of the city’s major construction took place while Uxmal was the capital of a Late Classic Maya state around 850-925 AD. After about 1000 AD, Toltec invaders took over, and most building ceased by 1100 AD.

While much work has been done at the popular tourist destination of Uxmal to consolidate and restore buildings, little in the way of serious archeological excavation and research has been done. The city’s dates of occupation are unknown and the estimated population (about 15,000 people) is only a rough guess. Most of the city’s major construction took place while Uxmal was the capital of a Late Classic Maya state around 850-925 AD. After about 1000 AD, Toltec invaders took over, and most building ceased by 1100 AD.

Maya chronicles say that Uxmal was founded about 500 AD by Hun Uitzil Chac Tutul Xiu. For generations, Uxmal was ruled over by the Xiu family. It was the most powerful site in western Yucatán, and for a while, in alliance with Chichén Itzá, dominated all of the northern Maya area. Sometime after about 1200, no new major construction seems to have been made at Uxmal, possibly related to the fall of Uxmal’s ally Chichén Itzá and the shift of power in Yucatán to Mayapan. The Xiu moved their capital to Maní, and the population of Uxmal declined.

Some of the more noteworthy buildings include:

The Governor’s Palace, a long low building atop a huge platform, with the longest façades in  Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica.

Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica.

The Adivino (aka Pyramid of the Magician or the Pyramid of the Dwarf), is a stepped pyramid structure, unusual among Maya structures in that its layers’ outlines are oval or elliptical in shape, instead of the more common rectilinear plan. It was a common practice in Mesoamerica to build new temple pyra- mids atop older ones, but here a newer pyramid was built centered slightly to the east of the older pyramid, so that, on the west side, the temple atop the old pyramid is preserved, with the newer temple above it. In addition, the western staircase of the pyramid is situated so that it faces the setting sun on the summer solstice.

The structure is featured in one of the best known tales of Yucatec Maya folklore, “el enano del Uxmal” (the dwarf of Ux- mal), which is also the basis for the structure’s common name. Multiple versions of this tale are recorded. It was popularised after one of these was recounted by John Lloyd Stephens in his influential 1841 book, Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatán. According to Stephens’ version, the pyramid was magically built overnight during a series of challenges issued to a dwarf by the gobernador (ruler or king) of Uxmal. The dwarf’s mother (a bruja, or witch) arranged the trial of strength and magic to compete against the king.

The structure is featured in one of the best known tales of Yucatec Maya folklore, “el enano del Uxmal” (the dwarf of Ux- mal), which is also the basis for the structure’s common name. Multiple versions of this tale are recorded. It was popularised after one of these was recounted by John Lloyd Stephens in his influential 1841 book, Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatán. According to Stephens’ version, the pyramid was magically built overnight during a series of challenges issued to a dwarf by the gobernador (ruler or king) of Uxmal. The dwarf’s mother (a bruja, or witch) arranged the trial of strength and magic to compete against the king.

The Nunnery Quadrangle (a nickname given to it by the Spanish; it was a government palace) is the  finest of Uxmal’s several fine quadrangles of long buildings. It has elaborately carved façades on both the inside and outside faces.

finest of Uxmal’s several fine quadrangles of long buildings. It has elaborately carved façades on both the inside and outside faces.

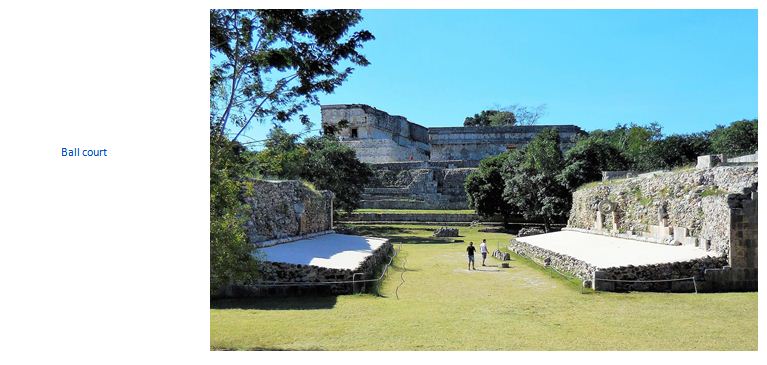

A large Ballcourt for playing the Mesoamerican ballgame. Its inscription says that it was dedicated in 901 by the ruler Chan Chak K’ak’nal Ajaw, also known as Lord Chac (before the decipherment of his corresponding name glyphs).

A number of other temple-pyramids, quadrangles, and other monuments, some of significant size, and in varying states of preservation, are also at Uxmal. These include North Long Building, House of the Birds,  House of the Turtles, Grand Pyramid, House of the Doves, and South Temple. The majority of hieroglyphic inscriptions were on a series of stone stelae unusually grouped together on a single platform. The stelae depict the ancient rulers of the city. They show signs that they were deliberately broken and toppled in antiquity; some were re-erected and repaired.

House of the Turtles, Grand Pyramid, House of the Doves, and South Temple. The majority of hieroglyphic inscriptions were on a series of stone stelae unusually grouped together on a single platform. The stelae depict the ancient rulers of the city. They show signs that they were deliberately broken and toppled in antiquity; some were re-erected and repaired.

A further suggestion of possible war or battle is found in the remains of a wall which encircled most of the central ceremonial center. A large raised stone pedestrian causeway links Uxmal with the site of Kabah, some 18 km to the south. Archaeological research at the small island site of Uaymil, located to the west on the Gulf coast, suggests that it may have served as a port for Uxmal and provided the site access to the circumpeninsular trade network.

Modern history of the ruins

The first detailed account of the ruins was published by Jean Frederic Waldeck in 1838. John Lloyd  Stephens and Frederick Catherwood made two extended visits to Uxmal in the early 1840s, with architect/draftsman Catherwood reportedly making so many plans and drawings that they could be used to con- struct a duplicate of the ancient city (unfortunately most of the drawings are lost). Désiré Charnay took a series of photo graphs of Uxmal in 1860. Some three years later, Empress Car lota of Mexico visited Uxmal.

Stephens and Frederick Catherwood made two extended visits to Uxmal in the early 1840s, with architect/draftsman Catherwood reportedly making so many plans and drawings that they could be used to con- struct a duplicate of the ancient city (unfortunately most of the drawings are lost). Désiré Charnay took a series of photo graphs of Uxmal in 1860. Some three years later, Empress Car lota of Mexico visited Uxmal.

Sylvanus G. Morley made a map of the site in 1909 which included some previously overlooked buildings. The Mexican government’s first project to protect some of the structures from risk of collapse or further decay came in 1927. In 1930 Frans Blom led a Tulane University expedition to the site. They made plaster casts of the  façades of the “Nunnery Quadrangle”; using these casts, a replica of the Quadrangle was constructed and displayed at the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago, Illinois.

façades of the “Nunnery Quadrangle”; using these casts, a replica of the Quadrangle was constructed and displayed at the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago, Illinois.

The plaster replicas of the architecture were destroyed follow- ing the fair, but some of the plaster casts of Uxmal’s monuments are still kept at Tulane’s Middle American Research In- stitute. In 1936, a Mexican government repair and consolidation program was begun under José Erosa Peniche. Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom visited on February 27, 1975 for the inauguration of the site’s sound and light show (this explains why it seems so dated). When the presentation reached the point where the sound system played the Maya prayer to Chaac (the Maya rain deity), a sudden torrential downpour occurred. Gathered dignitaries included Gaspar Antonio Xiu, a descendant of noble Maya lineage, the Xiu. Unfortunately, Microbial biofilms have been found degrading stone buildings at Uxmal and Kabah.

Download the full edition or view it online

Dan and Lisa Goy, owners of Baja Amigos RV Caravan Tours, have been making Mexico their second home for more than 30 years and love to introduce Mexico to newcomers.