By Terry Sovil from the July 2010 Edition

Part 1

Ports fascinate me. I wondered if people really understood the immense complexity and technology that goes into a modern day port. I decided information on our port may be more interesting with a foundation to build on. Next issue we’ll talk more about our own Port of Manzanillo.

Ports are the economic engines of a country and if accidently shutdown the economic impact can reach billions of dollars per day. In 2007 over 80% of world trade was carried on the sea. A World Bank study showed that a country wanting to export but having inefficient ports essentially made it 60% farther away from target markets.

Everything is scheduled! That’s easy to say but consider: a terminal in a port knows when their ship is scheduled to arrive. More importantly, they know when it has to depart because another ship is waiting for dock space. They know the contents of the ship, the crew, where a shipment came from, where it is going, who transported it to the ship, where it will go once unloaded etc. How is all this managed? There is high -level oversight of all of the entities that have to work together as a team. Here is a more detailed list to consider: private companies, government agencies, port and maritime authorities, law enforcement, fire departments, coast guards, customs, immigration, health inspection, agricultural inspection, shipping lines, terminals, depots, tug boats, weather (wind, waves, tide actions), lighthouses and navigation markers. Large ports work 365 days a year, are data driven and must address security, disaster, emergency, safety and operating incidents.

Add threats of terrorism, attack, crime, theft or drugs and you have to monitor suspicious people, weight inconsistencies, missing seals, hazardous materials, dangerous combinations, container stacks , leakage, ruptures, collisions, derailment, fires, floods and intrusions. The resources to regulate and respond to these are often separate enforcement groups such as the military, police, fire, regulatory agencies, first responders, gate management, access control, cargo identification, drivers, timing of ship arrivals and departures, berthing, crew and passenger access validation, public and contractor personnel, container loading/unloading, truck & train arrival and departure, empty containers, inspections, crane operations, carrier coordination and you can start to see where a port is a huge intersection of commerce and interests.

, leakage, ruptures, collisions, derailment, fires, floods and intrusions. The resources to regulate and respond to these are often separate enforcement groups such as the military, police, fire, regulatory agencies, first responders, gate management, access control, cargo identification, drivers, timing of ship arrivals and departures, berthing, crew and passenger access validation, public and contractor personnel, container loading/unloading, truck & train arrival and departure, empty containers, inspections, crane operations, carrier coordination and you can start to see where a port is a huge intersection of commerce and interests.

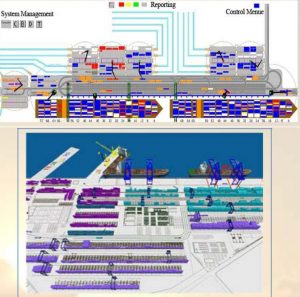

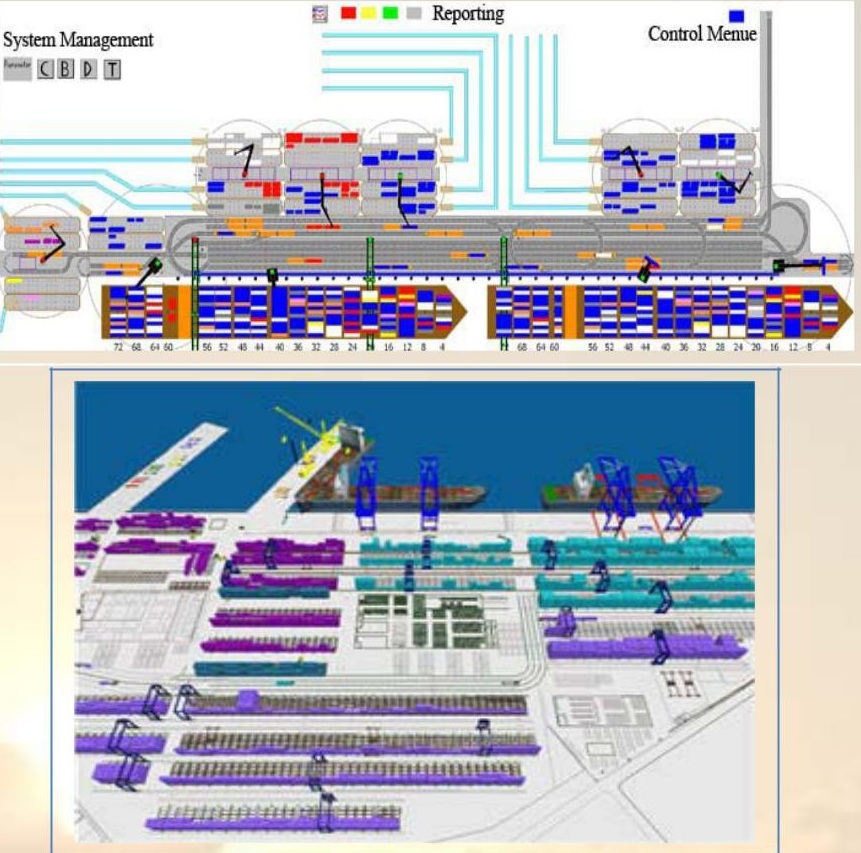

Bottom line: a port’s reputation is based on efficiency at loading and unloading, “crane-moves” per hour, which impacts how long it takes a ship to come into port, offload, and get back out. The diagrams (top right) are not the Port of Manzanillo but it offers an overview of all of the activity at a single terminal inside a major port:

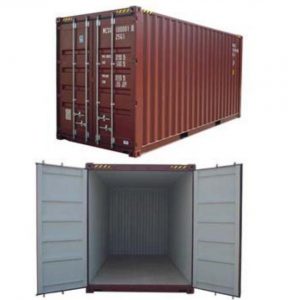

A common thread is the ubiquitous “container”. Invented in 1955, it evolved into an “intermodal container”. It is not only a shipping container but processes and methods of loading and locking them onto ships, trailers, railcars etc. It is an 8 foot (2.4m) tall by 8 foot (2.4m) wide box in 10 foot (3m) units made from 25mm (0.98 inch) thick corrugated steel. The design incorporates a twist-lock mechanism located in all eight corners of the box. These mechanisms allow the container to be lifted, secured, stacked and transferred. The designers patented it and gave the containers.

The container gave birth to the term “TEU” or Twenty-foot Equivalent Unit. The term is a measurement of the amount of cargo that is transferred within a port. The most common size today is the 40 foot (12m) container.

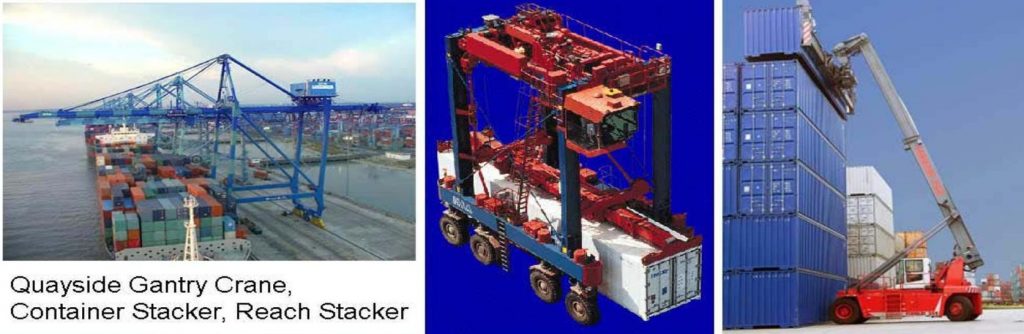

If you are in the vicinity of the port you can see the various types of cranes in operation. There are several that are used in Manzanillo and other large ports. The first is a gantry type crane at the quay or dock to load/unload a ship. These cranes are still commonly manually operated by highly skilled operators. Imagine a 40’ (12m) container being slammed into the side of a ship or a truck.

Another form of the gantry crane is for container handling and stacking. These cranes can run on rail or on rubber tires. The rubber tire models can turn all 4 tires in any direction to allow this crane high mobility. The height of this crane determines how many containers you can stack in a given area.

Also used are the reach stacker types of cranes, as well as forklifts etc. Containers are moved about the terminal by small tractors and light trailers.

Each terminal determines how to layout its allocated area based on the type of cargo they will receive and select the cranes they need for their operation. These decisions impact the port in terms of the types of ships that can be serviced and the cargo that they carry.

Container ships are designed to transport containers. Each area of the ship is marked and every container has a unique serial number. They can be bar-coded and scanned and the container ship and terminal know exactly where each container is located on the ship. Using a computer program they assign unloading by crane operator and know which truck must pick it up and where to take it (another truck, storage, customs, inspection, and rail). This allows an efficient port terminal to load and unload a ship at the same time.

There are other ship types that can handle non-containerized cargo including: ROLO, Roll On Roll Off, that carry cars that are driven on and off; reefers, refrigerated ships, for fresh produce or frozen fish; tankers, carry liquid, usually oil or gas; cruise ships, carry tourists, and bulkers that carry bulk cargo such as iron ore pellets.

Download the full edition or view it online

—

Terry is a founding partner and scuba instructor for Aquatic Sports and Adventures (Deportes y Aventuras Acuáticas) in Manzanillo. A PADI (Professional Association of Dive Instructors) Master Instructor in his 36th year as a PADI Professional. He also holds 15 Specialty Instructor Course ratings. Terry held a US Coast Guard 50-Ton Masters (Captain’s) License. In his past corporate life, he worked in computers from 1973 to 2005 from a computer operator to a project manager for companies including GE Capital Fleet Services and Target. From 2005 to 2008, he developed and oversaw delivery of training to Target’s Loss Prevention (Asset Protection) employees on the West Coast, USA. He led a network of 80+ instructors, evaluated training, performed needs assessments and gathered feedback on the delivery of training, conducted training in Crisis Leadership and Non-Violent Crisis Intervention to Target executives. Independently, he has taught hundreds of hours of skills-based training in American Red Cross CPR, First Aid, SCUBA and sailing and managed a staff of Project Managers at LogicBay in the production of multi-media training and web sites in a fast-paced environment of artists, instructional designers, writers and developers, creating a variety of interactive training and support products for Fortune 1000 companies.

You must be logged in to post a comment.