By Terry Sovil from the May 2010 Edition

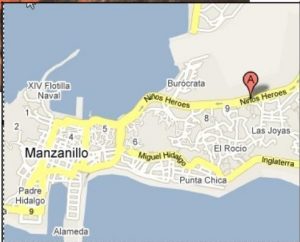

On your next trip into Centro take note that the street “Miguel de la Madrid” turns into a street named “Niños Héroes” near San Pedrito. This name is often used on streets, squares or schools throughout Mexico as well as once appearing on an MXP 5000 banknote and currently on a MXN 50 coin. The Mexico City Metro station is also named after them. Who are these Niños Héroes, known as “Boy Heroes” or the “Heroic Cadets”? Few Mexican heroes have touched hearts so much as these six young men aged 13 to 19.

The Mexican-American war was in its final stages. The Boy Heroes stood their ground against invading forces from the U.S.A. on 13 September, 1847 at the Battle of Chapultepec, defending Mexico City’s Chapultepec Castle which was the Mexican army’s military academy at that time. The Castle and the hill it stands on was a strategic target. Despite its position 200’ feet above the rest of the countryside there were insufficient men to defend it. American forces outnumbered the Mexicans in both force and weapons.

Ordered to fall back and return home by their commanders, General Nicolás Bravo and General José Mariano Monterde the Cadets refused and stayed at their posts. They fought valiantly until all were killed. The last survivor, Juan Escutia, legend says, leapt from Chapultepec Castle wrapped in the Mexican flag to prevent it from being taken by the enemy. Their bravery is honored by a monument at the entrance to Chapultepec Park.

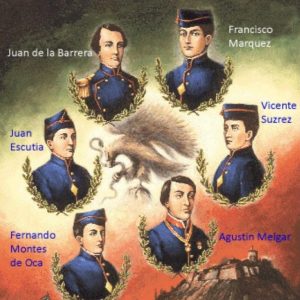

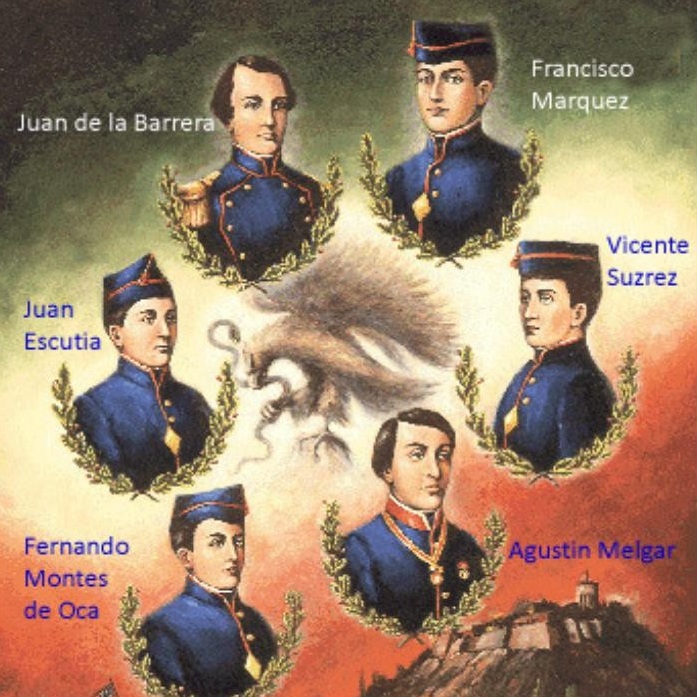

Niños Héroes were:

Juan de la Barrera who enlisted at the age of 12 and was admitted to the Academy on 18 November 1843. A lieutenant in the military engineers he died defending a gun battery at the entrance to the park. Aged 19, he was the oldest of the six.

Juan Escutia was born in Tepic between 1828 and 1832 and admitted to the Academy on 8 September 1847. This brave cadet was found wrapped in the flag on the east flank of the hill, alongside that of Francisco Márquez.

Francisco Márquez was born in Guadalajara, Jalisco in 1834, applied to the Academy on 14 January 1847. A note included in his personnel record says his bullet-riddled body was found on the east flank of the hill, alongside that of Juan Escutia. Only 13 years old at the time of his death, he was the youngest of the six.

Agustín Melgar born in Chihuahua, Chihuahua, sometime between 1828 and 1832 applied to the Academy on 4 November 1846. His personnel record tells how he found himself alone trying to defend the north side of the castle.

After shooting one of the enemy to death he took refuge behind mattresses in one of the rooms. Grievously wounded he was placed on a table and found dead beside it on 15 September, after the castle fell.

Fernando Montes de Oca was born in Azcapotzalco, currently a borough of the Federal District, between 1828 and 1832. Applying to the Academy on 24 January 1847 his personnel record reads: “Killed for his country on 13 September 1847.”

Vicente Suárez, born in 1833 in Puebla, Puebla, he applied to the Academy on 21 October 1845. His record notes: “Killed defending his country at his sentry post on 13 September 1847. He ordered the attackers to stop, but they continued to advance. He shot one, stabbed another in the stomach with his bayonet and was killed at his post in hand-to-hand combat. He was killed for his bravery, because his youthfulness made the attackers hesitate, until he attacked them.”

“Brave men don’t belong to any one country. I respect bravery wherever I see it.’’ Harry S Truman

The bodies of the six youths were buried in Chapultepec Park in an unknown location. In 1947 their remains were found, identified and were re-interred on 27 September 1952 at the Monument to the Heroic Cadets in Chapultepec.

On 5 March 1947, before the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Chapultepec, Harry S. Truman placed a wreath at the monument and spent a few silent minutes. On this visit Truman experienced crowds larger than he had seen anywhere. He returned “Vivas!” and broke away from security escorts to shake hands. He said later to the Mexican Legislature, where he pledged again his ‘Good Neighbor Policy’, “I have never had such a welcome in my life”. He reminded a crowd of American citizens that they, too, were ambassadors. Word spread like wildfire and he too became an instant hero. One Mexican engineer was quoted as saying: “One hundred years of misunderstanding and bitterness wiped out by one man in one minute. This is the best neighbor policy.” When reporters asked him why he visited the monument Truman replied “Brave men don’t belong to any one country. I respect bravery wherever I see it. “

Download the full edition or view it online

—

Terry is a founding partner and scuba instructor for Aquatic Sports and Adventures (Deportes y Aventuras Acuáticas) in Manzanillo. A PADI (Professional Association of Dive Instructors) Master Instructor in his 36th year as a PADI Professional. He also holds 15 Specialty Instructor Course ratings. Terry held a US Coast Guard 50-Ton Masters (Captain’s) License. In his past corporate life, he worked in computers from 1973 to 2005 from a computer operator to a project manager for companies including GE Capital Fleet Services and Target. From 2005 to 2008, he developed and oversaw delivery of training to Target’s Loss Prevention (Asset Protection) employees on the West Coast, USA. He led a network of 80+ instructors, evaluated training, performed needs assessments and gathered feedback on the delivery of training, conducted training in Crisis Leadership and Non-Violent Crisis Intervention to Target executives. Independently, he has taught hundreds of hours of skills-based training in American Red Cross CPR, First Aid, SCUBA and sailing and managed a staff of Project Managers at LogicBay in the production of multi-media training and web sites in a fast-paced environment of artists, instructional designers, writers and developers, creating a variety of interactive training and support products for Fortune 1000 companies.

You must be logged in to post a comment.