By Suzanne A. Marshall from the April 2015 Edition

It’s been the subject of many conversations over the winters here in Manzanillo:

It’s been the subject of many conversations over the winters here in Manzanillo:

“Did you see that surf today?”

“It seems the beach has suddenly gone from smooth mounds of deep sand, to cliff like structures!”

“It’s been clear and sunny for days; why are these enormous waves pounding the beach?”

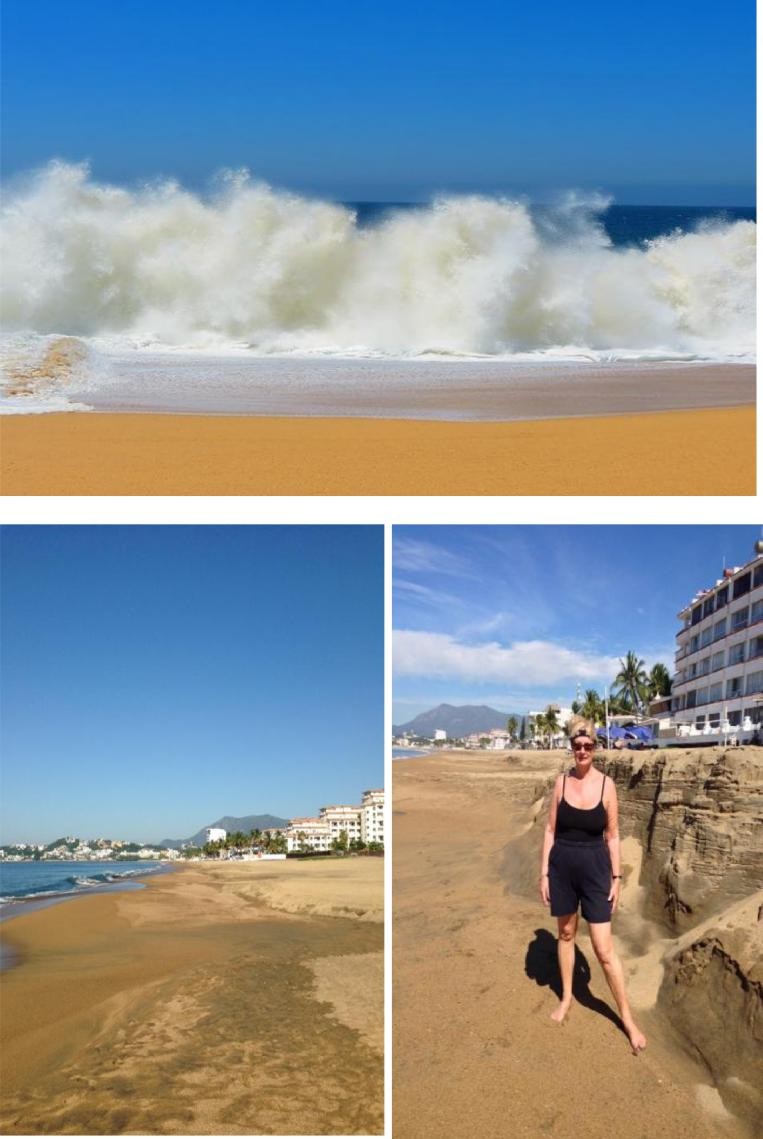

And they certainly do pound the beach! So much so, that I find it to be like mesmerizing theatre. Sitting on the terrace and watching the rising surf topple over in a foaming rage and smack the beach with such a force and a roar you cannot hold conversation in those moments. The ones we wait for and relish are what we call the ‘doubles.’ When one wave is pouring back out and the next incoming wave collides with it sending water and mist crashing high into the air. We can literally feel the mist in the wind. Often the force of the surf can be felt underfoot in our condo as it reverberates through the ground and our 12” thick brick and concrete walls and floors. Completely awesome!

It was a conversation with my young local ‘dentista’ who also happens to be a ‘surfer girl’ that got me searching for answers. Since I had surmised that the correlation with the tides had little bearing with the roaring surf which was relentlessly active for days and nights, my curiosity was truly piqued. The information I gleaned is complex and very scientific. So I’m providing a very simplistic overview on this subject.

Basically, the term for the waves pounding our beaches (and those around the world) is ‘ocean Swell.’ By definition Swell is a series of mechanical waves that propagate from the interface between water and air, often called ‘Surface gravity.’ Here’s the catch. Surface gravity waves are not generated by the immediate local wind, rather by distant weather systems, where wind blows for a period of time over a ‘fetch’ of water. Swell waves often have a long wavelength and their size depends upon the strength, duration and size of the body of water.

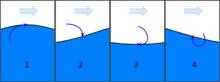

The phases of an ocean surface wave: 1. Wave Crest, where the water masses of the surface layer are moving horizontally in the same direction as the propagating wave front. 2. Falling wave. 3. Trough, where the water masses of the surface layer are moving horizontally in the opposite direction of the wave front direction. 4. Rising wave

The great majority of large breakers such as on the beach in Manzanillo result from distant weather systems over a fetch of ocean. So the swell that we have been so captivated by could have begun formation days earlier.

Factors impacting the size of Swell are much too complex for this article but suffice it to say briefly that they are; wind speed, area size of open water, wind duration, and depth of water. All of these factors form a swell and are an actual transfer of energy from pressure.

Storms that are thousands of nautical miles away can propagate the longest swells which are ultimately dissipated when they hit the shorelines. On a global perspective, these waves can vary in distance from 20,000km (half the distance round the globe) to 2000km.

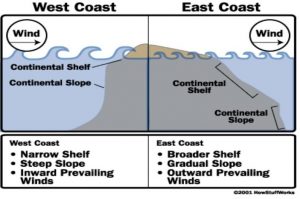

Another interesting thing I came upon during my searches was the fact that the waves on the West Coast, U.S.A. (and I am assuming Mexico) are larger than the waves on the East Coast. This would likely account for the many popular surfing coastlines from California well on down to southern Mexico. The reason for this is the differing continental shelves. The West Coast has a narrow and steep continental shelf with inward prevailing winds. The East Coast has a much broader gradual shelf with outward prevailing winds (Diagram 1.). As well, the Pacific Ocean on the West Coast has a greater expanse than the Atlantic. This means that the ‘fetch’ (the distance over which the wind blows) is greater on the West Coast. To use a familiar term for North Americans/Canadians, the waves grow from the ‘snowball’ effect. The farther you roll a snowball the bigger it gets.

One of the other surprises for me was finding out that the larger Swell season does not occur during the winter months. In fact it occurs mostly between July and September on average. That being the case, if I thought the dramatic surfs in Manzanillo during the winter (we are here from November to April) are pretty awesome, I can’t imagine what the sea sends in during the summer season. Wow!

Download the full edition or view it online

—

Suzanne A. Marshall hails from western Canada and has been living the good life in Manzanillo over the past 8 years. She is a wife, mom and grandma. She is retired from executive business management where her writing skills focused on bureaucratic policy, marketing and business newsletters. Now she shares the fun and joy of writing about everyday life experiences in beautiful Manzanillo, Mexico, the country, its people, the places and the events.

You must be logged in to post a comment.