By Kirby Vickery from the May 2015 Edition

I have been putting this series together for a number of months with the help of friends both of Anglo and of Hispanic heritage. There has arisen a discussion as to the rightfulness of the northern Mexican border, its acquisition, and placement geographically. I have found an excellent article and am forwarding most of it below to help clarify and explain the history and validity of this treaty:

Treaty of Guadalupe Is Still Relevant Today

by Patrisia Gonzales & Roberto Rodriguez

From 1998 [1848] to 1998 marks the 150th anniversary of the Mexican-American War. The most important individual anniversary will be the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which took place on Feb. 2, 1848, and which formally ended the two-year conflict between the United States and Mexico.

While some people (and many U.S. courts) see the treaty as dead, others see it as the basic document that governs relations between both countries. Still others see it as a living human rights document that pertains to people of Mexican origin residing in the United States.

Many of us were raised with the idea that the war against Mexico was simply pretext for stealing its territory, and the treaty, negotiated under military duress and signed by a corrupt dictator, simply formalized the theft of half of Mexico’s territory–a violation of international law. (As a result of the war, Mexico lost land that now makes up the Southwestern United States).

While many Mexican Americans view the treaty in this context, it did guarantee Mexicans and their descendants who remained in the ceded territories certain political rights, including land rights. But by the end of the century, most Mexicans had lost their land, either through force or fraud.

During the early Chicano movement in the 1960s, New Mexico land rights crusader Reies Lopez Tijerina and his Alianza movement invoked the Treaty of Guadalupe in their struggle. In 1972, the Brown Berets youth organization also invoked it in their symbolic takeover of Catalina Island, off the Southern California coast.

For more than 15 years, many Chicano indigenous groups have cited the treaty in their struggle for the human rights of Chicanos in international forums, such as the U.N. They maintain, however, that the Mexican and indigenous peoples living in what is today the Southwest U.S. were not signatories. Native American peoples have also referred to it in their legal disputes.

Despite the fact that “It’s not our treaty,” says Rocky Rodriguez, national director of the Denver-based National Chicano Human Rights Council, Chicanos in the United States today are also covered by it.

When it comes to fighting for human rights cases, especially those of land theft and law enforcement abuse, seeking relief through U.S. courts is basically of no use to Chicanos, says Rodriguez. People of Chicano/Mexican origin rarely win when they use or encounter the judicial system, she says.

Richard Griswold del Castillo, a San Diego State University history professor, considers the treaty a living document, and studies the subject in his recent book, “The Treaty of Guadalupe: A Legacy of Conflict.” (Griswold del Castillo, Richard. University of Oklahoma Press. July 31, 1990) Upon examining the document and its 23 articles negotiated by both countries, the most startling thing that stands out is that article 10 is missing. That article, which was deleted by the U.S. Senate upon ratification, explicitly protected the land rights of Mexicans. Additionally, article 9, which deals with citizenship rights, was weakened.

The key to understanding the treaty, however, is not so much what’s in it, but rather, what isn’t in it. According to precedents set by U.S./Indian treaties, people do not automatically lose their rights when they lose a war. People possess inherent and universal human rights and when treaties are negotiated, the people involved can lose only the rights specifically agreed upon.

In “American Indians, American Justice,” by Vine Deloria and Clifford M. Lytle (Vine, Deloria. Jr. and, Lytle.Clifford M. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1983.), the author’s state that courts, in recognizing the past exploitation and the use of force against American Indians, developed a set of judicial rules in dealing with disputes. In effect, they are guiding principles when dealing with U.S./Indian treaties. According to the author’s one of the rules states: “Treaties reserve to Indians all rights that have not been granted away.” This is known as the “Reserved Rights Doctrine.”

It thus follows that Mexicans in the U.S. did not lose their rights, unless that was stipulated in the treaty. And of course, no such stipulation was made. Also, these same rules call on judges to interpret treaties in the manner that reasonable people would interpret them. And it can be assumed that reasonable people don’t “give away” their lands or rights in treaties.

Reflecting over the United State’s history of violated treaties, Rodriguez says, “Indian prophecies predicted trickery in the north [America] and brute force in the south. Here [in the Southwest U.S.], both have been used.

“i i Gonozales, Patrisia, and Rodriguez, Roberto. “Treaty of Guadalupe Is Still Relevant Today.” . July 31, 1990.

From my own classes I can tell you that you may or may not agree with the reasoning, the cause, or even the legality of this treaty but, that isn’t my point here. The thrust of the above tends to expose the exploitation of the Hispanic and Indian populations living in the area affected by the treaty by the American government. I do know that the Mexican government was invited to make a joint survey of the border and that the Mexican government apparently had problems fielding teams but in the end accepted the boundaries surveyed by the U.S. In reality there were two teams contracted from each country. One ran east to west from El Paso and the other worked the other way from San Diego. My intent is to present the legends of the Aztec who were long gone from this area when this agreement was made between the two countries. This I shall do.

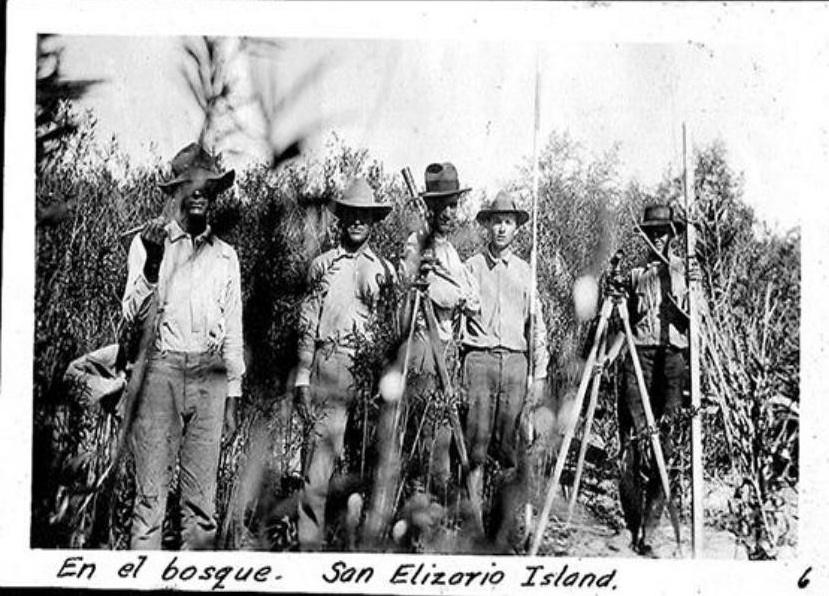

There is an interesting side story which my Grandfather (the dude in the middle) tells about the Treaty of Hidalgo. Historically the treaty led to the establishment of the International Boundary and Water Commission in 1889. Its function put the onus on the U.S. to: Maintain the border. Allocate waters between the two nations. Provide for flood control and water sanitation.

What isn’t much remembered was the fact that the Rio Grande River flooded every spring. There is a plain which runs down the eastern part of central New Mexico. This plain extends just west of Mount Franklin of

which El Paso is built around. Juarez Mexico shares this pass and these floods were wiping out most of the Mexican city every year. The fix took several years with the building of Elephant Butte and Cabrillo Dams in New Mexico and an extensive irrigation and water control system in El Paso County.

My Grandfather did most of the surveying of the outlay of Cabrillo and was running a survey crew in 1917 trying to establish a solid Rio Grande River course just south of El Paso. James Easter (‘JB’ to his friends) tells that they actually had gotten a little lost on this island in the river when they were discovered and captured by the Mexican Army. Please understand that the so called “Border War” between Mexico and the U.S. had just ended and nerves along the border were frayed at best. General Blackjack Pershing had returned to Fort Clark Springs in Del Rio (a few hours south of El Paso). One of his lieutenants was later to command the taking of northern Africa, Italy, and the Battle of the Bulge. George Patton got his training under Pershing during this small ‘war.’

My grandfather tells of waking up one morning surrounded by the Mexican Army. He and his crew were marched and trucked to a prison outside Juarez. He also stated that when the local commandant got word of this capture, their treatment changed a great deal. The entire team was then wined and dined and put up in the finest accommodations until they could be repatriated. The commandant made my grandfather promise to tell the news papers that everyone was well treated. And, this he did.

Download the full edition or view it online

—

Kirby was born in a little burg just south of El Paso, Texas called Fabens. As he understand it, they we were passing through. His history reads like a road atlas. By the time he started school, he had lived in five places in two states. By the time he started high school, that list went to five states, four countries on three continents. Then he joined the Air Force after high school and one year of college and spent 23 years stationed in eleven or twelve places and traveled all over the place doing administrative, security, and electronic things. His final stay was being in charge of Air Force Recruiting in San Diego, Imperial, and Yuma counties. Upon retirement he went back to New England as a Quality Assurance Manager in electronics manufacturing before he was moved to Production Manager for the company’s Mexico operations. He moved to the Phoenix area and finally got his education and ended up teaching. He parted with the university and moved to Whidbey Island, Washington where he was introduced to Manzanillo, Mexico. It was there that he started to publish his monthly article for the Manzanillo Sun. He currently reside in Coupeville, WA, Edmonton, AB, and Manzanillo, Colima, Mexico, depending on whose having what medical problems and the time of year. His time is spent dieting, writing his second book, various articles and short stories, and sightseeing Canada, although that seems to be limited in the winter up there.

You must be logged in to post a comment.