By Kirby Vickery from the January 2018 Edition

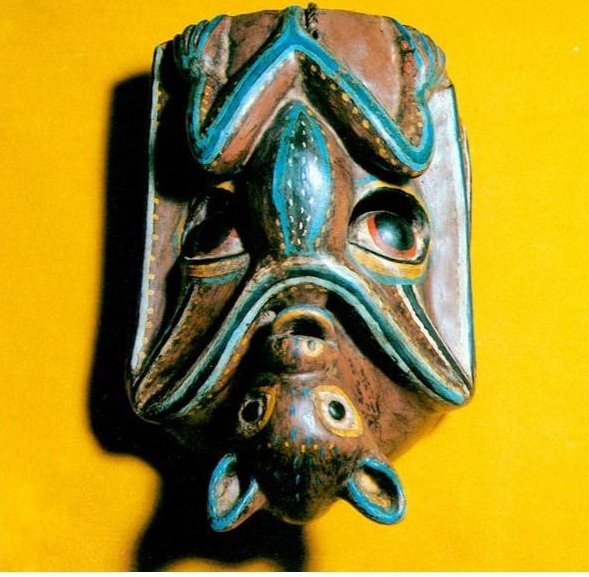

Reminiscent of Batman, the traditional painted wooden bat mask in this (main) picture from Atliaca, Guerrero, Mexico has a telltale clue the carved skull on its body to the darker side of the bat in Mexican folklore. Given that Mexico is actually the home of vampire bats, it shouldn’t come as a great surprise to know that the bat had many associations in the past with death and blood(y) sacrifice… (Written/compiled by Ian Mursell/Mexicolore)

Photo credit: Ian Mursell/Mexicolore

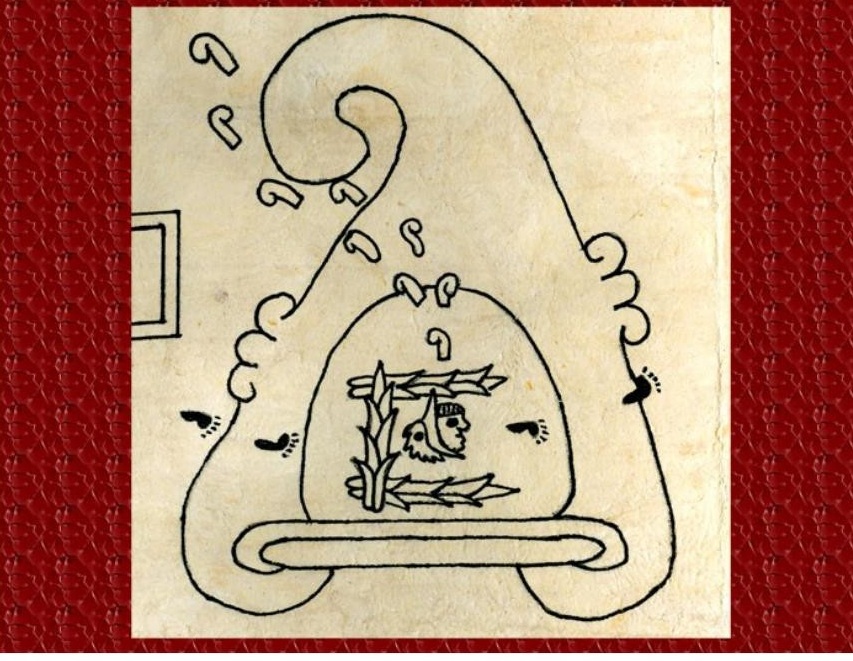

A creature of the night, the bat has, for obvious reasons, been traditionally linked in Mesoamerican imagery and legends with darkness: its natural habitat of a cave dark, sheltered and damp provides an easy connection, not only with the mother’s womb and place of origin of humankind, but also with the underworld and world of the dead, according to many preHispanic cultures.

Some experts believe ancient Mexicans particularly the Maya may have made a link between the typical habit of a bat of grabbing fruit from trees and the ritual practice of decapitation: notice the presence of an obsidian blade of sacrifice at the very top of the stone bat image on the front of the famous Aztec altar of animals associated with darkness and death (the other creatures carved on the altar are a scorpion, a spider and an owl). Esther Pasztory believes the paper rosette on the head of the creature and the streamers (both of which appear on all four sides of the altar) depict the‘tzitzimime’ greatly feared star demons of darkness that dived head-first from the heavens.

With the power of flight, the upsidedown posture, and the strong association with night and the powers of the dark, the bat is a creature that bridges the sky/heavens (above) and the underworld (below); not surprisingly, the bat has traditionally been cast as a supernatural creature with deadly powers. In the famous Quiché ‘Popul Vuh’ text, the death bat god of the underworld, Camazotz, uses his power to cut off the head of one of the Hero Twins. References to bat imagery go back as far as Olmec times (Mexico’s ‘mother culture’).

A strikingly beautiful bat mask, some 2,000 years old, was found in the early 20th century at the famous archaeological site of Monte Albán, near Oaxaca: possibly designed to hang from the belt or chest, this fine Zapotec bat figure, made of jade mosaic, shows some similarity to a jaguar (lord of the night) though you may notice the large crest on the top of the forehead.

Not all bat associations were of death, destruction and sorcery, however. Just as death carries in it the seeds of new life, so the bat was recognized as having an important role to play in supporting life. As Elizabeth Benson writes, ‘Some of the plants most important to people in the New World tropics are bat-dependent.’ To give just one example, provided by UK bat expert Mary Louise Crosby, “Many different kinds of fruit-eating bats LOVE fresh figs. The bats digest their meal of figs quickly. The seeds pass through the bats’ digestive tracts and are expelled in feces or droppings as the bats fly or roost. In a single night, a single bat could plant thousands and thousands of fig tree seeds over acres of countryside.’ Fig tree bark paper, incidentally, was an important material for manuscript writing in ancient Mexico.

Reflecting the duality in so much of ancient Mexican beliefs, we end with a positive story of the bat, a Cora legend recorded a century or more ago in Mexico by Carl Lumhotz:

In the beginning, the earth was flat and full of water, and therefore the corn rotted. The ancient people had to think and work and fast much to get the world in shape. The birds came together to see what they could do to bring about order in the world, so that it would be possible to plant corn.

First they asked the red-headed vulture, the chief of all the birds, to set things right, but he said he could not. They sent for all the birds in the world, one after another, to persuade them to perform the deed, but none would undertake it.

Photo credit: Donald Cordry from Mexican Masks by Donald Cordry, 1980, courtesy of University of Texas Press

At last came the bat, very old and much wrinkled. His hair and his beard were white with age, and there was plenty of dirt on his face, as he never bathes. He was supporting himself with a stick, because he was so old he could hardly walk. He also said that he was no equal to the task, but at last he agreed to try what he could do. That same night, he darted violently through the air, cutting outlets for the waters; but he made the valleys so deep that it was impossible to walk about, and the chiefs scolded him for this.

“Then I will put everything back as it was before,” he said.

”No, no!” they all said. “What we want is to make the slopes less steep, and to leave some level land, and do not make all the country mountains.”

This the bat did, and the chiefs thanked him for it. Thus the world has remained up to this time.

Download the full edition or view it online

—

Kirby was born in a little burg just south of El Paso, Texas called Fabens. As he understand it, they we were passing through. His history reads like a road atlas. By the time he started school, he had lived in five places in two states. By the time he started high school, that list went to five states, four countries on three continents. Then he joined the Air Force after high school and one year of college and spent 23 years stationed in eleven or twelve places and traveled all over the place doing administrative, security, and electronic things. His final stay was being in charge of Air Force Recruiting in San Diego, Imperial, and Yuma counties. Upon retirement he went back to New England as a Quality Assurance Manager in electronics manufacturing before he was moved to Production Manager for the company’s Mexico operations. He moved to the Phoenix area and finally got his education and ended up teaching. He parted with the university and moved to Whidbey Island, Washington where he was introduced to Manzanillo, Mexico. It was there that he started to publish his monthly article for the Manzanillo Sun. He currently reside in Coupeville, WA, Edmonton, AB, and Manzanillo, Colima, Mexico, depending on whose having what medical problems and the time of year. His time is spent dieting, writing his second book, various articles and short stories, and sightseeing Canada, although that seems to be limited in the winter up there.