By Tommy Clarkson on the December 2019 Edition

Family Burseraceae

Also known as Paper Bark Tree, Gumbo-Limbo Tree, Naked Indian, Copperwood, Turpentine Tree, Mulatto Stick, West Indian Birch or Tourist Tree

Within the greater family as a whole, there are some 600 species in 15 genera, including species that yield frankincense and myrrh. (I guess you might say, “That makes good scents!”) The Bursera simaruba, however, has other interesting uses and intriguing qualities!

This unique but highly apt common name came about as a result of Americans (Gringos) who, in visiting our magnificent, sunbathed beaches, all too often, are oblivious to the severity of the tropical sun. And as a result of their over exposure like this tree they turn red and peel in somewhat, paper like appearing shreds (Read: bad sun burn!) Accordingly, as one might expect, Sunburned Gringo Tree is native to the tropical zone ranging from southern Florida, through the Caribbean islands, including Mexico to Brazil, Columbia, Nicaragua and Venezuela.

A most intriguing tree that flourishes in both wet and dry season, the Bursera simaruba can grow rather rapidly to between sixty to 100 feet (18.29 – 30.48 meters) tall. In parts of Central America, densely planted ones serve as windbreaks and also aid in erosion control on hillsides. Here in Mexico, in the Sayulita area, I know that straight pieces of its wood are used for fence posts. Intriguingly, often, when employed in this way, the cutting resurrects itself, growing new roots and becomes a living fence.

This wood is light-weight, light in color and soft. In our youth, we may well have often sat astride some from this very species in that, in the United States, it was carved to make the horses for merry go rounds! Haitians make drums from its trunk; the West Indians use its somewhat turpentine scented trunk resin to make glue, incense, varnish and water repellent coatings. Nature, herself, provides the berries as an important food source for an array of migratory bird species.

Like so many tropical plants, the Sunburned Gringo tree has various ethnobotanical, curative and health treatment applications. The itch of poison ivy and other plants, in addition to the pain of insect stings, gout and muscle sprains, can be alleviated through the application of its resin by members of some indigenous, native cultures. Tea made from the bark and leaves, mixed with sugar, has been used to treat low blood pressure. It is used in the treatment of dropsy, dysentery and yellow fever. It is purported to be an effective diaphoretic, diuretic, purgative and vulnerary.

The Maya called it chakáh and used it to relieve skin irritations and scoriations (scrapes or abrasions). (I know, I should have just said those words in the first place but have so few opportunities to use it, I just had to!)

It has pinnately compound (for we lay folks, let’s just say they are featherlike) leaves. That unique, attractive, reddish bark peels away in thin flakes revealing a smooth and sinuous gray underbark. Its trunk is massive in size – two to three feet (.61 – .91 meters) in diameter. The tree has huge, irregular branches with a rounded, spreading crown. Its leaves are four to eight inches (10.16 – 20.32 cm) long and have three to seven oval or elliptic leaflets, each one to two inches (2.54 – 5.08 cm) long. They are semi-deciduous. As a result, they lose their leaves in early spring, prior to the arrival of its new leaves.

The Sunburned Gringo Tree blooms in our “winter,” These come in the form of small, inconspicuous flowers made up of three to five greenish petals arranged in elongated racemes (unbranched, indeterminate inflorescences bearing pedicellate flowers [flowers having short floral stalks called pedicels] along its axis). Both male and female flowers, generally, bloom on the same tree. Its dark red fruits are elliptical in shape, about a 0.5 in (1.3 cm) in length and take a year to mature.

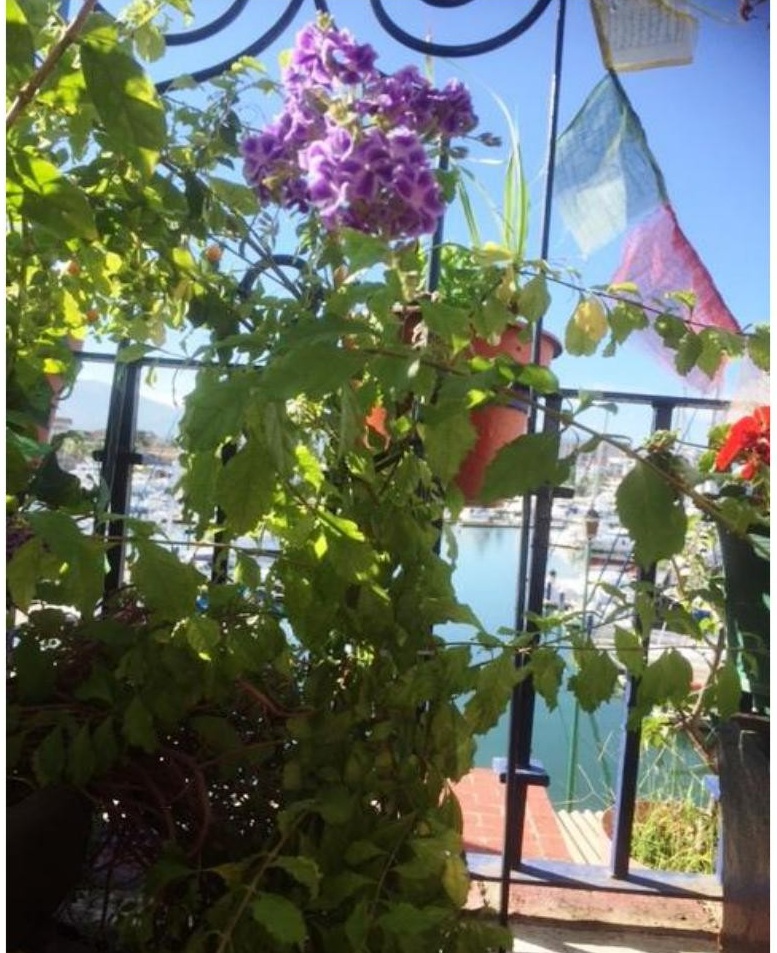

Almost constantly on the move, traveling all around planet Earth, generally doing botanical research with his students, several years ago, my pal Dr. Mark Olson of the Department of Biology at the National University of Mexico, graciously gave me four different species of Bursera. Never a conventional sort, I have been striving to keep them somewhat “bonsaiesque” at below six feet (1.83 meters) or so, growing them in large pots on my roof! (Yep, you’re correct, there’s never a dull or possibly, even all that normal moment here in Ola Brisa Gardens!)

The full edition or view it online

—

Tommy Clarkson is a bit of a renaissance man. He’s lived and worked in locales as disparate as the 1.2 square mile island of Kwajalein to war-torn Iraq, from aboard he and Patty’s boat berthed out of Sea Bright, NJ to Thailand, Germany, Hawaii and Viet Nam; He’s taught classes and courses on creative writing and mass communications from the elementary grades to graduate level; He’s spoken to a wide array of meetings, conferences and assemblages on topics as varied as Buddhism, strategic marketing and tropical plants; In the latter category he and Patty’s recently book, “The Civilized Jungle” – written for the lay gardener – has been heralded as “the best tropical plant book in the last ten years”; And, according to Trip Advisor, their spectacular tropical creation – Ola Brisa Gardens – is the “Number One Tour destination in Manzanillo”.