By David Fitzpatrick from the December 2010 Edition

Part 2: The Count-Down to War

In the mid 1840s, Mexico was experiencing a period of political turbulence. At one point, the bitter rivalries between factions verged on civil war. In a series of revolving-chair government changes, there were four presidents in a period of one year. Added to the political instability were the perpetual fiscal problems and the inability of the central government to pay its debts.

In the mid 1840s, Mexico was experiencing a period of political turbulence. At one point, the bitter rivalries between factions verged on civil war. In a series of revolving-chair government changes, there were four presidents in a period of one year. Added to the political instability were the perpetual fiscal problems and the inability of the central government to pay its debts.

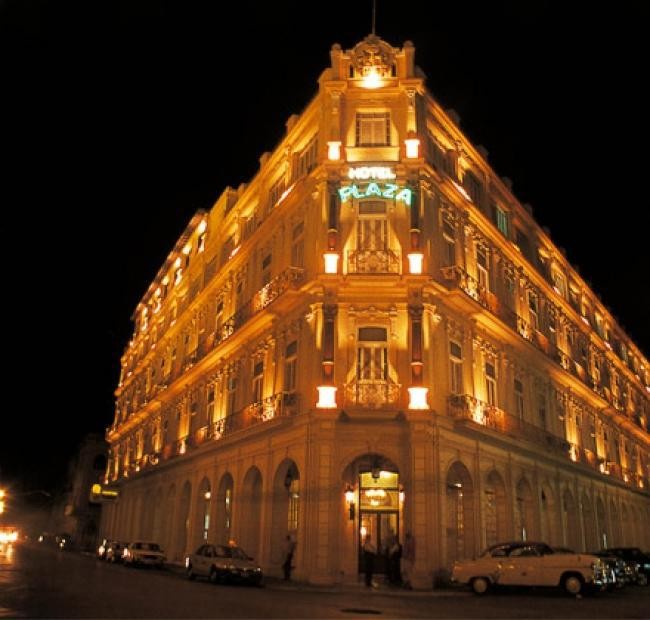

The full gravity of Mexico’s problems was beginning to be known to the international community and the vultures were circling. Britain and France were taking a greedy interest. The British foreign minister of the time, the highly predatory Earl of Palmerston, was an unapologetic imperialist, constantly ready to assert British power anywhere in the world. His ambassador in Mexico wrote to him, urging him to: “establish an English population in the magnificent Territory of Upper California…..(It is) by all means desirable … that California, once ceasing to belong to Mexico, should not fall into the hands of any power but England …”. This was the kind of talk Lord Palmerston liked to hear and concrete action might well have followed, but before the message reached him in London, the ministry had changed and a “Little England” government was in power.

In Washington, as early as 1841, President John Tyler (1841 – 1845) proposed an agreement whereby America would look the other way while Britain captured the port of San Francisco, in return for which, the Oregon Territory would be extended north to the 54:40 parallel of latitude. This arrangement would have given the Canadian Province of British Columbia to the United States as far north as about Prince Rupert.

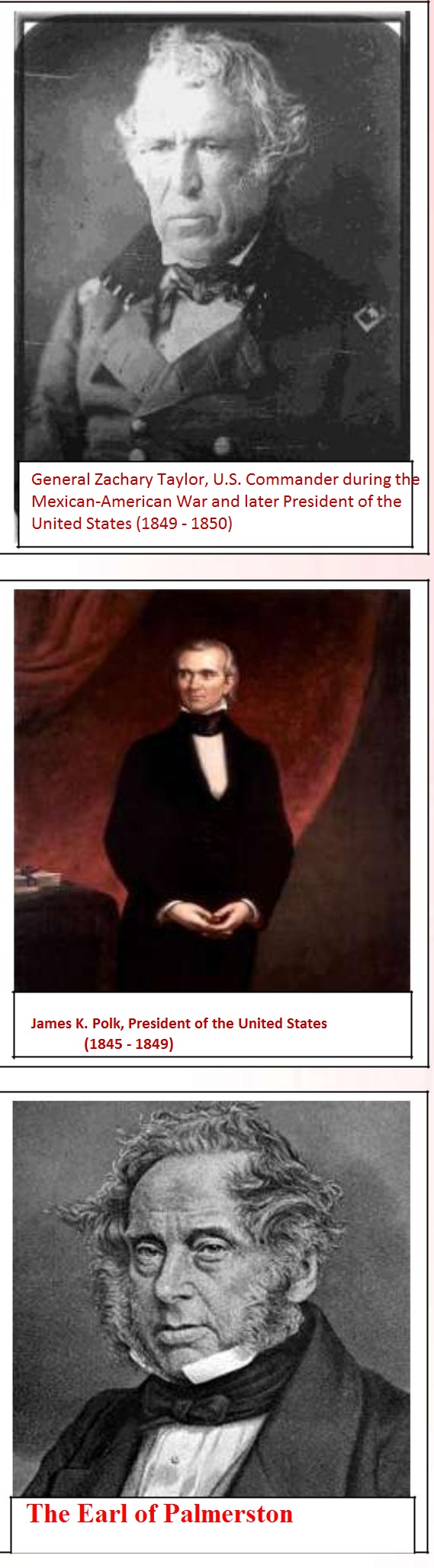

In March 1845, a new President, James Polk, took office. With the arrival of Polk, American expansionism once more took center stage. He was determined to extend the frontiers of the U.S. to the Pacific and realized that if he did not act quickly, Britain and France might beat him to the draw. He therefore undertook a series of ventures aiming to annex, conquer, colonize, purchase, or otherwise acquire various Mexican territories. Failing that, he intended, at the very least, to provoke the Mexican government into war.

Polk’s opening salvo came in June 1845 when he announced his policy with regard to Texas. He meant to work towards the annexation of Texas (which was still an independent republic) to the United States as soon as possible. This required a considerable amount of delicate negotiation with the American Government as a large number of northern Whigs were opposed to Western expansionism in general and the annexation of Texas in particular. They feared that the Southern slave-owning states would seek to absorb parts of Mexico and admit them to the U.S. as slave states.

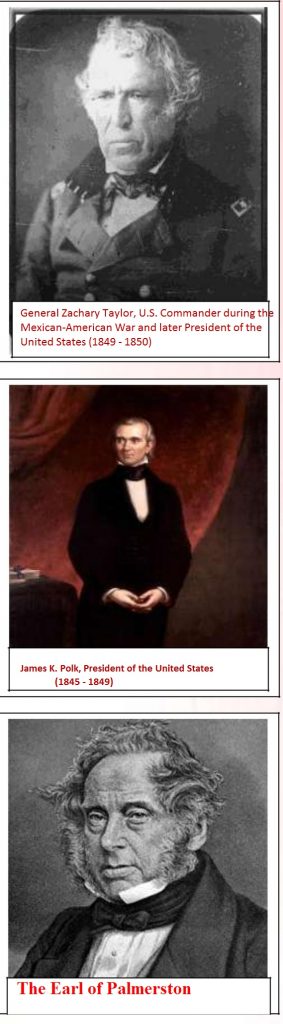

Polk declared himself ready to defend Texas against Mexican “aggression”, even though it was not yet a part of the United States. He therefore sent General Zachary Taylor with a significant military force to the banks of the Nueces River, considered at the time to be the border between Texas and the rest of Mexico.

At the same time, he instructed the American naval squadron in the Pacific to be ready to seize California ports at once if Mexico declared war on the United States.

In November 1845, he sent John Slidell as a secret ambassador to the Mexican Government authorized to offer $25,000,000 to purchase California and the territory of Santa Fe de Nuevo Mexico, a very large area comprising several present-day U.S. states. Slidell was also sanctioned to forgive over $3,000,000 in debts owed by the Mexican Government to U.S. citizens

The Slidell embassy provoked increased dissension inside the Mexican power structure, some factions being ready to negotiate, while others cried “treason”. José Joaquin de Herrera, the Mexican president of the moment, was forced to resign when he was perceived as being too ready to listen to American demands.

On December 29, 1845, Polk finally achieved his key objective: after a long and bitter debate, the U.S. Congress formally admitted Texas as the 28th State of the Union. This represented a major provocation to the Mexican Government which still regarded Texas as a rebellious province which would one day be re-assimilated into Mexico. They had frequently warned that the annexation of Texas would constitute a casus belli. Mexico therefore immediately severed relations with the United States.

While Congress was debating, John Fremont, officially an explorer commissioned by the U.S. Government, proceeded with a small army through the Salinas Valley to Santa Cruz on the California coast. When questioned by Mexican authorities, he explained that he was looking for a beach-side residence for his mother. Sceptical, and alarmed by the size and military hardware of Fremont’s party, they ordered him to leave. But instead, he built a fortress, flying the American flag, and indicated his firm determination to annex California to the United States. It was only upon the intervention of Thomas Larkin, the U.S. Consul in Monterey, who was not a war enthusiast, that Fremont agreed to leave the territory. But he returned the following year in time to be present for California’s declaration of independence from Mexico.

Early in 1846, General Zachary Taylor who had been camped beside the Nueces River, received orders from President Polk to advance to the banks of the Rio Grande, some 150 miles to the south. As Mexico regarded the Nueces River as the border, the military occupation of the corridor between the Nueces and the Rio Grande was a substantial violation of Mexican territory and sovereignty. In Mexican eyes, it was the gravest provocation to date. It was becoming clearer every day that war was now inevitable.

As so often happens in tense international situations, the final catalyst was a minor incident of apparently little importance. On April 25, 1846, a small detachment of U.S. soldiers patrolling in the disputed corridor between the two rivers, was set upon by a force of 2,000 Mexican cavalry. There was a small skirmish lasting only a few minutes, but sixteen American soldiers were killed. This was the casus belli that President Polk was looking for. He did not miss his opportunity. Two weeks later, in an inflammatory message to Congress, he stated that:

“Mexico has passed the boundary of the United States, has invaded our territory and shed American blood upon American soil”.

For Congress, there was only one possible reaction to such an incident: On May 13, 1846, two days after the

President’s message, the United States formally declared war on Mexico. Ten days later, President Paredes issued a statement on behalf of the Mexican Government which constituted, to all practical purposes, a declaration of war. It was not until July 7, 1846, that the Mexican Congress officially declared war on the United States.

Next Month: The War

Download the full edition or view it online

You must be logged in to post a comment.