By David Fitzpatrick from the November 2010 Edition

Part 1: Texas

When Mexico won its independence from Spain in 1810, its territory was more than twice what it is today. Stretching from Guatemala in the south to the Oregon Territory in the North, it included the present day US States of California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas, as well as parts of Colorado, Wyoming, and Oklahoma. In a series of disastrous events during the 1830s and 1840s, including wars, colonization, settlements, and purchases, Mexico was to lose more than half of its original territory.

Following Independence, the Government of Mexico adopted a sort of homestead policy to attract settlers to its under populated northwestern provinces. In particular, land grants were made in the Province of Texas to anyone who would swear allegiance to Mexico and adopt Catholicism. Many Americans answered the call. As early as 1810, Moses Austin, a Missouri banker and his son Stephen received a large land grant and eventually settled more than 300 American families on their land. Other Americans followed and by the 1830s, Americans in Texas outnumbered Mexicans.

Inevitably, difficulties arose, due in large part, to the differences in mentality of the two peoples and the unfamiliarity of the new American colonists with Mexican Government procedures. The question of Manifest Destiny1 was also very much on the horizon.

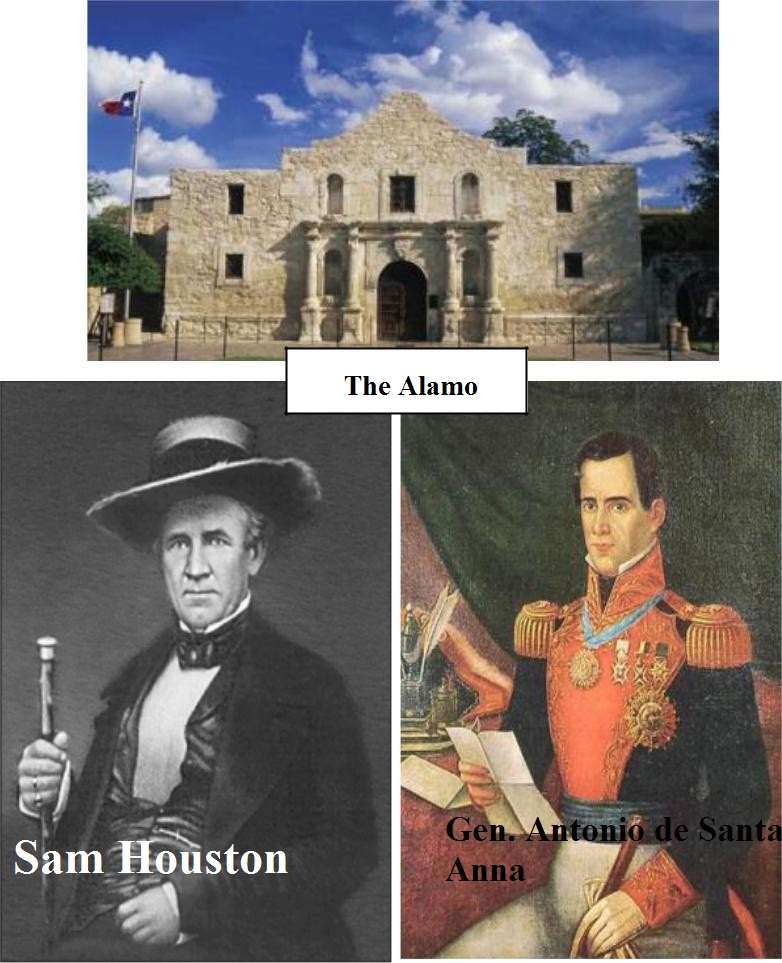

In 1836, following a series of unpopular measures by President Santa Anna, the American majority in Texas declared independence. Sam Houston, a former Governor of Tennessee was named Commander-in-Chief of the exas militia and subsequently elected President of the Republic of Texas.

Santa Anna reacted with immediate military action: within days of the declaration of independence, he attacked the Alamo, a mission and fortress near San Antonio, killing all but two of the American defenders. But shortly thereafter, Santa Anna was defeated; and taken prisoner by Sam Houston at the battle of San Jacinto. He then signed the Treaty of Velasco, officially granting independence to Texas. The Mexican Congress refused to ratify this treaty, maintaining that it was coerced when Santa Anna was a prisoner.

But as they had no means of reclaiming Texas, it was de facto independent. The new Republic was immediately recognized by Britain, France, and the United States.

The question of annexation to the United States, naturally enough, was soon on the table, but it encountered resistance in…………the United States Congress. The issue of western expansionism divided the Congress between the Southern Democrats, who favored extension of America’s frontiers, on the one hand; and the Northern Whigs (precursors of the “Anti-Slavery Republicans”) who suspected the Southerners of trying to tip the balance of power between free and slave-holding states. Certain Congressmen, including John Quincy Adams and Abraham Lincoln, opposed Manifest Destiny on principle. Texas, therefore, remained an independent republic for another 11 years.

It was not until the mid 1840s that the political climate radically changed and the future of Texas – and other parts of Mexico – was once more in question.

to be continued..

Download the full edition or view it online

You must be logged in to post a comment.