From the December 2015 Edition

As we have become a global community, Christmas traditions have also become globalized. Mexico’s  Christmas celebrations and the history of Mexican Christmas, known as Navidad, are no exception. Like most aspects of Mexico’s culture, Navidad resembles Spanish traditions but Navidad has also adopted other countries’ customs and shows a rich history of influence, bringing together components of Judaic, Spanish, German, Japanese and, since NAFTA, an increased US influence to its celebrations. Navidad celebrations lasts for weeks and builds to a climax at midnight of December 24th when churches and celebrants at family gatherings light fireworks.

Christmas celebrations and the history of Mexican Christmas, known as Navidad, are no exception. Like most aspects of Mexico’s culture, Navidad resembles Spanish traditions but Navidad has also adopted other countries’ customs and shows a rich history of influence, bringing together components of Judaic, Spanish, German, Japanese and, since NAFTA, an increased US influence to its celebrations. Navidad celebrations lasts for weeks and builds to a climax at midnight of December 24th when churches and celebrants at family gatherings light fireworks.

Navidad, whose Judaic/Christian roots are attributed to a Belgian priest, nicknamed Fray Pedro, formally known as Fray Pieter van der Moere or Fray Pedro de Gante; (c.1480-1572) was born in Geraardsbergen, Belgium. Fray Pedro, a relative of King Charles V, and also thought to be a bastard son of Maximilian I, was a member of the very first Franciscans to come to the colony of New Spain. He devoted his life to teaching the indigenous population of Christianity and Christian traditions, introducing carved Nativity scenes and blending European Christmas celebrations with celebrations honoring Huitzilopochtli, an Aztec deity. The introduction was agreeable to the indigenous peoples and so began new celebrations blending Christian, Aztec and a blending of other traditions.

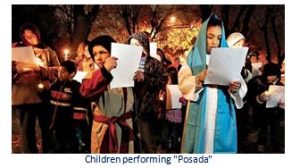

Navidad festivities begin on December 12, the day of the Virgin Guadalupe, with the Posadas. The Posada is symbolic of Joseph and Mary’s effort to look for a place to give birth to their baby, Jesus. The Posada is celebrated with a series of huge parades or pilgrimages, with participants carrying candles along with figurines, and now more commonly plastic dolls, of baby Jesus.

Navidad festivities begin on December 12, the day of the Virgin Guadalupe, with the Posadas. The Posada is symbolic of Joseph and Mary’s effort to look for a place to give birth to their baby, Jesus. The Posada is celebrated with a series of huge parades or pilgrimages, with participants carrying candles along with figurines, and now more commonly plastic dolls, of baby Jesus.

The march of the Posada involves people going to each house dressed as Joseph and Mary, reenacting the original, sacred event. Everywhere manger scenes, called Nacimientos, are displayed. After the posada on December 24th, people gather for midnight Mass after which the disassembly process is supplemented by hot chocolate, tamales, along with ham and turkey. Modern day celebrations of the Posada are enjoyed among family, friends, coworkers and especially school-aged children.

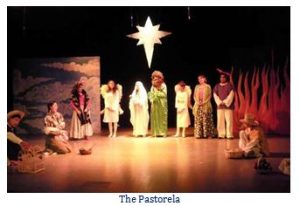

The next celebration is the Pastorela (the shepherd’s play). It is a common sight when Christmas is near. As the name implies, these dramatic pieces, performed by either professional or amateur companies, were traditionally designed to teach the stories of Christmas. Today, the performances focus on the shepherd’s story, improvised with humor, bawdy jokes and audience participation. Story lines tell of the shepherd’s struggles overcoming Satan’s temptations.

the name implies, these dramatic pieces, performed by either professional or amateur companies, were traditionally designed to teach the stories of Christmas. Today, the performances focus on the shepherd’s story, improvised with humor, bawdy jokes and audience participation. Story lines tell of the shepherd’s struggles overcoming Satan’s temptations.

Historically Santa Claus has not been a feature in Mexico’s version of Christmas. Now, commercially, the Santa Claus figure has become a strong, but incongruent, presence. Christmas trees, particularly artificial ones, are now common due to influence from Canada and the US, with the biggest part of celebrations now happening on Christmas Eve. In Spanish it is known as Noche Buena. Millions of people all over the country join both the Mass and Christmas Eve feast. An interesting detail is that the event is also called the Mass of the Rooster, because it is said that the only time that a rooster crowed at midnight was on the day that Jesus was born.

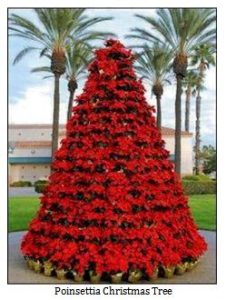

The color red is commonly seen during Navidad celebrations, owing to a dominance of poinsettia flowers used in festivals. These flowers, native to Mexico, have become the main floral arrangement, often stacked on frames into great Christmas trees.

The festivals and celebrations become merrier in the night. During the Posada parties, Mexicans will play a famous game called the “Piñata.” It’s a decorated jar or paper mâché figure filled with candies and sweets. The piñata will be hung either on tree branches from the ceiling. Traditionally, around the Christmas holidays, people decorate the piñata in a ball shape with 7 peaks around the side. Those peaks represent the seven deadly sins.

The festivals and celebrations become merrier in the night. During the Posada parties, Mexicans will play a famous game called the “Piñata.” It’s a decorated jar or paper mâché figure filled with candies and sweets. The piñata will be hung either on tree branches from the ceiling. Traditionally, around the Christmas holidays, people decorate the piñata in a ball shape with 7 peaks around the side. Those peaks represent the seven deadly sins.

Children will be blindfolded and take a turn to hit at the piñata with a stick till it breaks open and the candies pour out. A traditional song or cheer is sung for each blindfolded participant. The children will hunt for as many candies as they can once the piñata is broken. Piñatas used to be exclusively a Christmas feature but are now also used at birthdays and other celebrations.

The concept of this Holy day comes from a rich history, combined with many influences of immigrants to the country, as well as those of the indigenous population. Overall, Christmas in Mexico still includes the real concept of Christmas and a celebration of the birth of Christ as well as being a demonstration of the Mexican people’s love of unity with friends and family.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christmas_in_Mexico http://www.christmascarnivals.com/christmas-history/history-christmasmexico.html https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pedro_de_Gante

Download the full edition or view it online

Manzanillo Sun’s eMagazine written by local authors about living in Manzanillo and Mexico, since 2009

You must be logged in to post a comment.