By Robert Hill from the July 2011 Edition

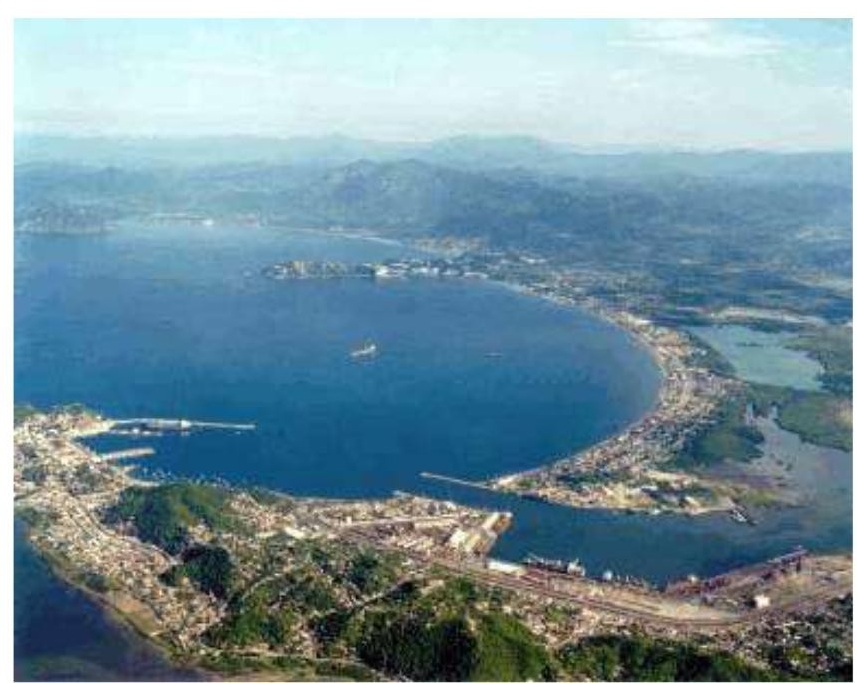

Humberto and Lupita are two of the wonderful friends I have met here in Manzanillo over the past 10 years. They were having a birthday party for Lupita at their beautiful home recently, and I was invited. I found myself seated next to Lupita´s father, a kindly old gentleman named Salvador Garcia who is 83 years old, but could pass for 70 We began to converse and I asked him many questions about his life here in this Western part of central Mexico. Before long we came to the startling realization that this was not the first time we had met!

A little chill ran down my spine when we discovered that he had helped harvest the oranges in my father´s orange groves, in Southern California, more than 60 years earlier, when he was in his 20´s and I was about 10.

Salvador was born into a dirt poor family in the town of Tamazula, Jalisco, not far from Ciudad Guzman. Salvador has lived in the same house his whole life, which has been enlarged and remodelled to accommodate his wife, Teresa, and their 4 children, including Lupita. When Salvador was a young man in Tamazula the only employment opportunity was at the huge sugar mill, which processed sugar cane from all over Jalisco.

He belonged to the sindicato (union) but the wages were very low and the work was seasonal because sugar cane was not available during the rainy summer months. It was next to impossible for a young man to raise a family and rise above a life of poverty. For these reasons Salvador became one of the adventurous young Mexicans who, along with his compañeros in the sugar mill union, took advantage of the Brasero program during the off season.

This program was a cooperative effort between the governments of Mexico and the United States, whereby migrant farm workers could legally work for a few months each year in the citrus groves of Southern California, the fields of the huge San Joaquin Valley in Central California, or in the orchards and fields of Washington state, Texas, Arizona and elsewhere. These young men did not relish the thought of leaving their families and beloved Mexico, even if for only a few months each year, but it was their only choice for escaping a life of extreme poverty. During the time they worked in the U.S. they would earn 3 times the money they made at the sugar mill in Jalisco.

Salvador and his compañeros made their way North by train, in the second class cars with not much more than wooden benches to sit or sleep on. The old steam engine would chug along all the way from Tamazula to Guadalajara, then North to the border to meet the labor contractor who had contracted with U.S. growers for their services. Once at their destination the braseros were housed in what looked like an army camp.

The brasero camp which served all of the orange and lemon growers in the Pomona Valley, was located in a eucalyptus grove on East Mission Blvd. in Pomona, about 40 miles east of Los Angeles. All of the citrus crops from the communities of Pomona, Claremont, Riverside, Redlands, Ontario, Upland, etc, were harvested by braseros from this camp. That is why I can say with a high degree of certainty that Salvador worked in the groves of my father and grandfather in Pomona, and he remembers being in the camp there.

This whole area, about 20 miles square, encompassed thousands of acres of almost solid citrus groves in Eastern L.A. County, Western San Bernardino County and Northern Orange County.

The camp, provided by the labor contractor, had war surplus army sleeping tents, a large mess tent for eating, and another for rest rooms and showers. The tents had wooden floors and low wooden walls, with canvases extending upward and forming the roofs. Each worker had his own cot to sleep on and a Mexican cook prepared the Mexican fare they liked. Each worker received a lunch of tortillas, beans and meat which they heated on a wood fired comal at the location they were working at.

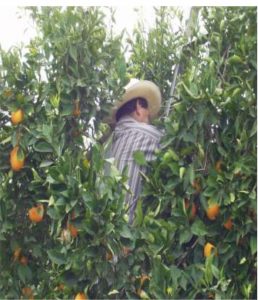

The braseros were transported to the job site in large trucks with benches and a canvass covering. The truck pulled a trailer loaded with the special ladders (wide at the base and narrow at the top) which allowed them to gain access to the fruit at the tops and inside branches of the orange trees. Oranges cannot be simply pulled from the branches because the stems would likely come out of the orange and it would quickly spoil.

It takes 2 hands to pick an orange; one to hold the fruit and the other to cut the stem with a small pair of side cutters. Each worker wore a large canvass bag with a wide, padded strap crossed over their shoulder and extending down to the ground. The bottom of the bag was open, but folded up and held closed with brass clips. When it was full of oranges he would hold the bottom of the bag over one of the large wooded “field boxes”, release the clips, and the oranges would fall out of his bag into the box. At the end of each days work my dad would drive our 1929 Model A Ford flatbed truck through the grove, onto which the field boxes of oranges would be loaded, and then it was off to the Sunkist packing house. Here they were inspected, graded and packed in smaller wooden crates.

The finest oranges were individually wrapped in paper and shipped by rail to large Eastern cities, while the smaller fruit was sold to processors for making juice. My dad used to laugh at the roadside stands which advertised “tree ripened oranges”, as there is no other way to ripen an orange!

I was a skinny kid of 8 – 12 years old during all of this and I especially liked the 3 weeks or so when the Mexican braseros came to pick our oranges. I was always out in the grove with them trying to communicate and help out. They seemed to like having me around and at times let me sample their muy picante food. One of them taught me some Spanish words which I later found out at our family dinner table, were very naughty words. My mother said she would wash out my mouth with soap and water if I ever repeated them. I was never sure how she knew what they meant, but the braseros had a big laugh the next day when they found out about it.

The thing I remember most was the music. Imagine standing in the middle of a twenty acre orange grove, and hearing the most heavenly sounds rising up from the trees, sung in 4 part harmony from men you could not see. One of them would begin singing a Mexican ballad or folk song, then all the rest would join in like a choir of 20 voices singing in perfect harmony. This was more than 60 years ago but I can still hear the sounds. I have since discovered that singing while working is an important part of the Mexican culture, mostly songs about every day life.

When the harvest was finished, Salvador and his friends would head South again with money in their jeans. They could hardly wait to see their wives and kids and to have a huge fiesta to celebrate their safe return.

MORAL OF THE STORY

First of all, this story proves that neighbouring countries can work together in ways that make sense. The Brasero program was a big plus for the U.S., whose work force did not want to perform what they considered to be menial labor. It also provided respectable and comparatively good wages for Mexicans trying to escape a life of poverty, within a legal structure. I do not believe that we can morally blame Latino workers for the mess which has been made of the U.S. immigration laws. Many of the migrant workers, like Salvador, did not return to Mexico when the crops were harvested, but stayed in the U.S. to make a new life for themselves.

For more than 4 decades the U.S. immigration authorities turned a blind eye to what was happening and did very little to enforce immigration laws. After all, there was no other source of labor for low paying jobs in America. One day someone started counting noses and discovered there were 20 million illegal immigrants in the U.S., mostly Latinos. The obscene situation we now see at the border is not about work or workers. It is about the insatiable desire America has for mind altering drugs, now about $200 Billion every year, much of which crosses the U.S./ Mexico border.

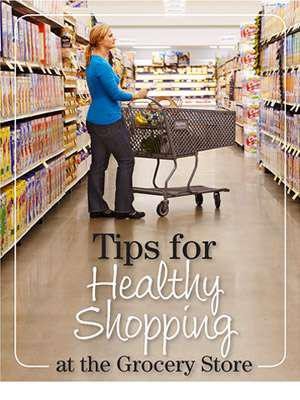

Secondly, this story is about how the Brasero program made a huge difference in the life of Salvador Garcia and the future generations of his family. Without it, his children would not have been able to go to the University and eventually become part of the emerging Mexican middle class. My friends, Lupita and Humberto met while he was studying agriculture at the University of Guadalajara. They married and after graduation, Humberto was offered a job as an agricultural advisor for the State of Colima, so they moved to Manzanillo.

They both worked hard and saved the money to buy 26 hectares (about 80 acres) of prime agricultural land in Colomos, on which they planted banana trees. Today they harvest and ship about 1,700 TONS of bananas every year. They have a beautiful home, drive new cars, and have become leaders in the business community. Their daughter, Paola, recently graduated from the University of Colima with a degree in nutrition. She is employed by the State Department of Health and maintains a private business as a nutrition consultant.

I am happy that Salvador Garcia has lived long enough to see all of this. I am also amazed and happy that we happened to bump into each other again after more than 60 years. Small world indeed.

Download the full edition or view it online

You must be logged in to post a comment.