By Manzanillo Sun Writer from the February 2016 Edition

One of Mexico’s greatest sources of pride is the beautiful beaches. For the tourism sector, the beaches represent an important feature of a visitor’s destination experience. Mexico long ago recognized that, in order to keep the beaches clean and enjoyable for locals and tourists (national and from farther afield), a comprehensive set of goals, strategies, plans and policies had to be created.

In 2003, the Clean Beaches Program was born and was rolled out nationwide. There are a number of agencies that guide or consult to the Program, such as:

- Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources (Secretaría de medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, SEMARNAT)

- Ministry of Health (Secretaría de Salud, SS), operating through the Federal Commission for Protection against Health and Sanitation Risks (Comisión Federal para la Protección contra Riesgos Sanitarios, COFEPRIS)

- Marines (Secretaría de Marina, SEMAR)

- Tourism Ministry (Secretaría de Turismo, SECTUR)

- Federal Attorney for Environmental Protection (Procuraduría Federal de Protección al Ambiente (PROFEPA)

- National Water Commission (Comisión Nacional del Agua, CONAGUA)

- Manzanillo’s Clean Beaches Committee was officially inaugurated in July of 2003.

Added to these are the many state and municipal agencies, several non-profit organizations and countless  experts and concerned business people from hotels, restaurants, port corporations and freight companies, and many residents of the affected or participating communities, many of whom are volunteering their time and expertise as divers, medical, oceanic and environmental experts, concerned locals and many more productive individuals. This author had the opportunity to serve alongside the Clean Beaches Committee colleagues and very dedicated group of participants, for a number of years.

experts and concerned business people from hotels, restaurants, port corporations and freight companies, and many residents of the affected or participating communities, many of whom are volunteering their time and expertise as divers, medical, oceanic and environmental experts, concerned locals and many more productive individuals. This author had the opportunity to serve alongside the Clean Beaches Committee colleagues and very dedicated group of participants, for a number of years.

The first phase of the project was to set goals, do research on the current state of affairs and prioritize a plan of action. The main goal in the beginning was to promote the improvement of tributaries, aquifers, fresh water bodies of water and reservoirs in order to prevent and remedy any prior pollution and pollutants, while respecting native ecology and raising the quality of life for the local populations. Next to benefit was the tourism population and, of course, the competitive element of the beach towns as a destination of choice.

Local destinations form committees and task forces to undertake the work at the regional level. They focus on these areas in order to organize their work and produce results:

- Healing of the zones and overall area improvement

- Monitoring and testing

- Education and awareness about policies and initiatives

- Local enforcement

- Research

- Ongoing resource management

- Evaluation and exchange of experiences and lessons learned

In the early days, they implemented a national system of bacteriological monitoring that started with 13 tourist destinations, 138 beaches in 10 states. They have since expanded to cover most of the country given that, though not all states have beaches, all do have tributaries.

With 157 km of coastline, Colima state was, of course, on the list of priorities for exploring the health of the local beaches and contributing waterways. The beaches of Manzanillo, Armería and Cuyutlán were among the ones being tested and researched.

Those of you living in Manzanillo year round will have seen, and possibly participated in, an annual cleanup of your local beaches, to remove garbage, debris, clear any blocked incoming waterways and possibly have participated in sample collection for testing. The garbage and other items are counted and records are kept to see how things improve year on year. Many people volunteer in the cleanup efforts. Of course some of the litter that is on the beach comes in with the tide but much is from local sources and so the committee makes a very great effort at educating the local population of the consequences of littering, including the fact that important egress waterways can be plugged during a flood, leading to more extensive flooding and often more tragic results.

Those of you living in Manzanillo year round will have seen, and possibly participated in, an annual cleanup of your local beaches, to remove garbage, debris, clear any blocked incoming waterways and possibly have participated in sample collection for testing. The garbage and other items are counted and records are kept to see how things improve year on year. Many people volunteer in the cleanup efforts. Of course some of the litter that is on the beach comes in with the tide but much is from local sources and so the committee makes a very great effort at educating the local population of the consequences of littering, including the fact that important egress waterways can be plugged during a flood, leading to more extensive flooding and often more tragic results.

In this photo, you can see a group of young people that participated in a beach clean up, in this case after the Jova hurricane of 2011. In that effort, as is the case on many other occasions, local businesses pitch in to buy latex gloves, rakes, garbage bags, supply the trucks to move the people and resulting garbage and assist in the proper disposal.

Of course, what is most of interest to those that go to sunbathe on Manzanillo’s beaches, and those that go to swim, surf, dive and snorkel in the waves, is how clean the water is as well as how clean the beach is, visually. This is where the important monitoring becomes of concern to the public.

In Manzanillo, there were originally 8 beaches in all, totaling 6 linear kilometers that were part of the program. The city added equipment to the program, initially including a farming tractor, a dump truck, a large beach sweeper, a large beachcombing machine and a 3-ton truck as well as assorted manual beachcleaning equipment. Original monitoring was done at 15 specific locations, all showing that Manzanillo’s beaches are within acceptable limits for use and enjoyment.

The local water commission (Comisión de Agua Potable y Alcantarillado de Manzanillo, CAPDAM) pitched in. They build the second phase of a residual water treatment plan and invested nearly 4,000,000 MXN in new infrastructure and improvements.

The program has included schools and communities in general in promoting the effective collection and disposal of solid waste and recyclables. This has all resulted in several hundred tons of material being diverted from landfills and from ending up in the water and on beaches. As well, local students have received prizes for initiatives that have aided in the efforts or have provided innovative solutions.

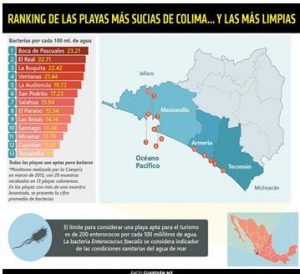

What is most of interest, locally, is the ranking or health of Manzanillo’s beaches. The measurement of enterococci (bacteria), as present in the water samples, is the measure of safe to swim in the waters. The limit that is considered save is 200 enterococci per 100 milliliters of water. Colima’s beaches consistently rank under 25 enterococci per 100 milliliters, meaning that all of the monitored beaches are considered more than safe, as seen in this graphic representation of the monitoring and results.

An important part of this program is to certify the beaches that are monitored. To become certified, several important rigors must be met or exceeded. To date, 18 beaches around the country have attained certification. Late last year, after more than a decade of dedicated effort, our very own playa La Audiencia (where Tesoro hotel is), was certified!

Source: Conagua

Download the full edition or view it online

Manzanillo Sun’s eMagazine written by local authors about living in Manzanillo and Mexico, since 2009

You must be logged in to post a comment.