By Kirby Vickery from the January 2018 Edition

By the time the community members of the Manzanillo Sun read this, most of the Holiday Season will have come and gone. As a matter of fact, one of my sources for Aztec Mythology list eleven major holidays in America throughout the year with Christmas listed as the top holiday. They report that Canada has ten national but many more regional and provincial holidays not celebrated by the total of the Canadian population. I suppose one could do a study as to the differences and with the modern trend of newscasting then set out to pick a winner as if the two countries were in some sort of a competition. But, we know they’re not and that’s not my topic anyway.

The Aztecs had various rituals and celebrations, most to honor the gods and bring them either rain, good crops or other such things. Most of their celebrations consisted of dances, music, different activities and sacrifices. For example, three times a year, the Aztecs had rain festivals, where they performed various activities and dancing to bring them a lot of rain for their crops to grow.

Please remember that the Aztecs followed the greater Mesoamerican time and date structure. They were a ‘Johnny-come lately’ force that took over the central Mexican area by unifying other tribes against the Toltecs. Then ruled with a strict priest class based society, absorbing not only the names and mythology of the forbearers’ gods, but their time tracking and history. Having never heard of Monday, Tuesday or even the month of August, they based their time on what was known by their priest class and the learned scholars of the towering societies before them. They had eighteen months and a 360-day year. Every month had at least one major religious ceremony honoring a god or gods. Most of these ceremonies were related to the agricultural season, the sowing of corn or the harvest of fruits. In almost all major ceremonies, an individual was chosen to impersonate the god. This person would be dressed as that god then coddled as if he or she was the god until the time of sacrifice.

Because the entire Aztec empire was built upon strict priest class control, human sacrifice was important, even vital. They embraced human sacrifice because of their gods. In their mythological story of the five worlds of creation, the gods, all the gods, had sacrificed their own blood and lives in creating the fifth world and everything in it, including humans. To honor the sacrifice of these gods, man, too, had to sacrifice his blood and life. To this end, most Mesoamerican cultures featured hu-man sacrifice, and most Aztecs went to the sacrifice willingly.

At the end of every 360-day year was the time of Nemontemi, a period of five days to even out the 365 days of a solar year. It was looked at as being a time of really bad luck and everybody, including the priests, stayed home fasting or eating very little just attempting to get through this time without mishap.

One representative ceremony happened in spring: Tlacaxipehualiztli.

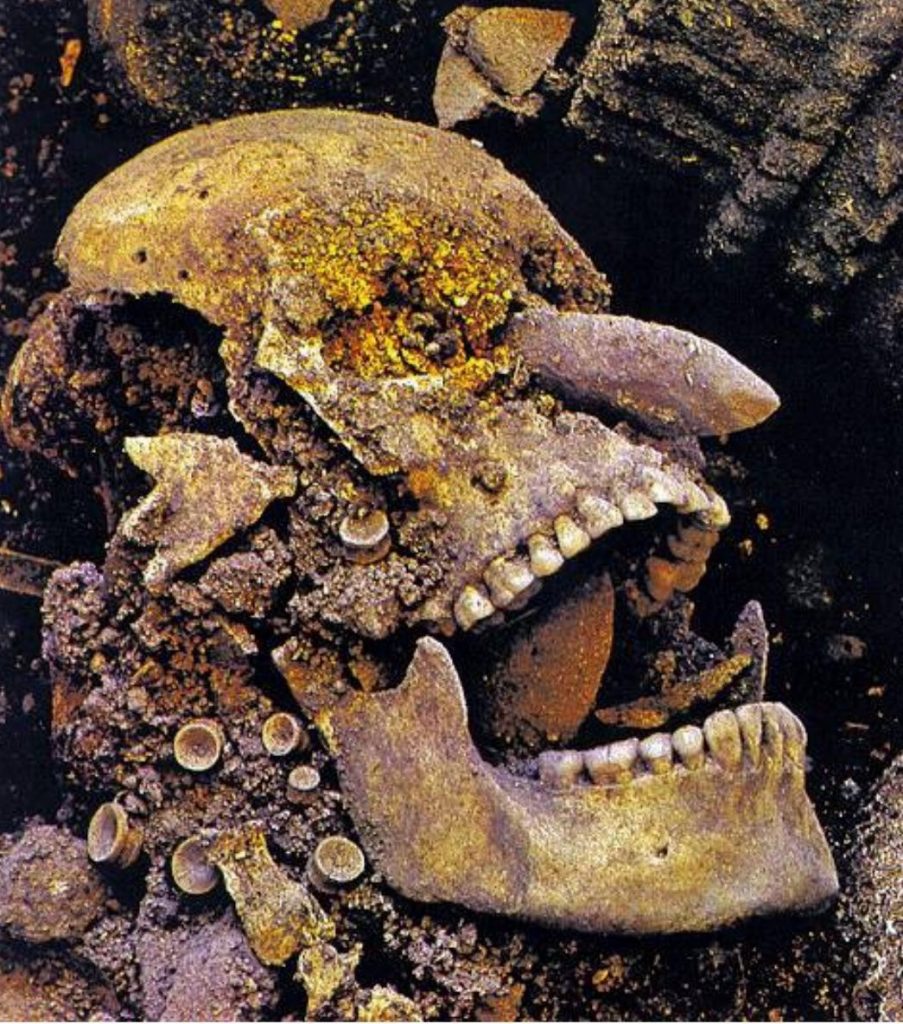

This honored the god of vegetation, Xipe Totec. This fertility ritual required the sacrifice of captured warriors. The warriors’ souls would have already turned to butterflies or hummingbirds when their skin was flayed from them, and the priests of Xipe Totec wore these human skins for the 20 days of the ceremony, while performing featured gladiatorial battles and military ceremonies.

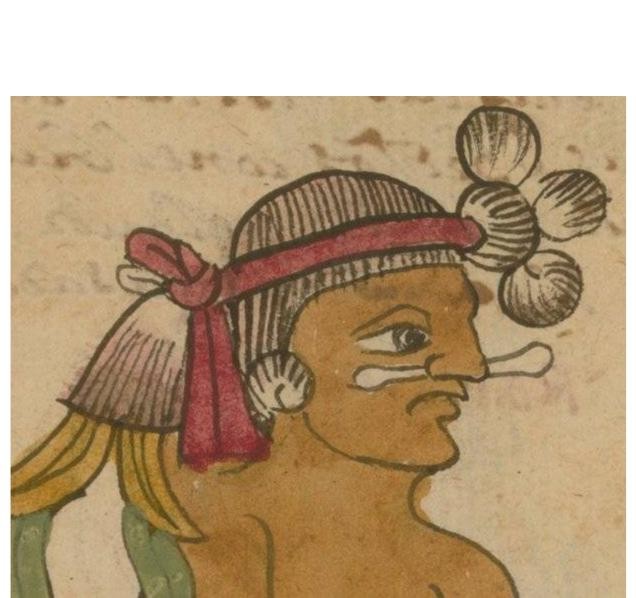

In a May ceremony called Toxcatl, an individual was chosen to represent Tezcatlipoca, the god of fate or destiny. The victim was treated as and portrayed the god until the time of his sacrifice. During these 17 day-long festivals, people indulged in feasting and dancing and small birds were sacrificed along with “Tezcatlipoca.”

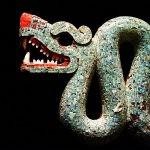

The celebration of Vernal Equinox (which happens in May) is held during the Chichén Itzá festival (which was started way be-fore the Aztecs came on the scene) and it is still a big thing today. During this time, at this place, a shadow in the form of a serpent appears on the wall of the El Castillo pyramid, which the Aztecs thought is their god, Quetzalcoatl.

What we call a century was their World Ending mark which reoccurred every fifty-two years and would happen in our November which was used at the start of their dry season. To them, the world ended and a new epic had to be built for the next world. This was when the New Fire Rites would align the new era. The most important happening for Toxiuhmolpilia was to make sure all the fires were out and all other activities would have to cease.

On Uixachtlan Hill, priests sacrificed a man and removed his heart. Then they started a fire in his chest and, from that fire, priests lit their torches and took them down the hill to the cities and the temples. In the dark of the night, Aztecs would watch the world’s fires lit again from the one sacrifice. New temple and house fires were all lit by the priests one at a time. People bought new clothes, and replaced their day-to-day tools and utensils. A new cycle would begin. Its purpose was to “give birth to the sun that would move on its path for another fifty-two years.” If the fire did not light, there was a fear shared amongst every individual in the empire that the world would be consumed by the power and forces of the night. This sacrificial ceremony allowed the Aztec people, and those who were under their control, to live for another fifty-two years in relative peace. This sacrifice allowed the proper orderly state of the cosmos its continued existence.

In the festival of Huey Tecuilhuitl women were honored. A young woman was called to take the place of the Goddess Xilolen. She had to sit before a brazier that represented the god of fire. Xiuhtecuhtli (also called Huehueteotl or Old God, Aztec god of fire) would be honored as four male captives were half-roasted and then killed in front of her. She would then be placed on top of the four dead bodies and be sacrificed. This rite was also performed to commemorate the victory of the god Tezcatlipoca over Quetzalcoatl.

The Templo Mayor (in Mexico City) was not simply a burial pyramid to the Aztecs. It was seen as a representation of the sacred mountain of Coatepec. It was on this sacred mountain that the mythic battle between the moon god and the sun god took place. “The newly born sun god Huitzilopochtli slew his warrior sister, the moon goddess, Coyolxauhqui, and flung her to the bottom of the mountain. The Aztec paying homage to this important battle between night and day would collect warriors and march them to the top of the Templo Mayor, make them dance and take part in the festivities, and then harshly cut off their heads and throw them down the steps of the temple. This was a visual reminder to the citizens of Tenochtitlan that sacrifice was essential to appease the gods and the cosmos.

Not all the festivities of the Aztec involved sacrifices. The Quecholli festival was a celebration of one of the four creators of the world, Mixcoatl. The Aztecs would celebrate this festival by going on a ceremonial hunt.

Download the full edition or view it online

—

Kirby was born in a little burg just south of El Paso, Texas called Fabens. As he understand it, they we were passing through. His history reads like a road atlas. By the time he started school, he had lived in five places in two states. By the time he started high school, that list went to five states, four countries on three continents. Then he joined the Air Force after high school and one year of college and spent 23 years stationed in eleven or twelve places and traveled all over the place doing administrative, security, and electronic things. His final stay was being in charge of Air Force Recruiting in San Diego, Imperial, and Yuma counties. Upon retirement he went back to New England as a Quality Assurance Manager in electronics manufacturing before he was moved to Production Manager for the company’s Mexico operations. He moved to the Phoenix area and finally got his education and ended up teaching. He parted with the university and moved to Whidbey Island, Washington where he was introduced to Manzanillo, Mexico. It was there that he started to publish his monthly article for the Manzanillo Sun. He currently reside in Coupeville, WA, Edmonton, AB, and Manzanillo, Colima, Mexico, depending on whose having what medical problems and the time of year. His time is spent dieting, writing his second book, various articles and short stories, and sightseeing Canada, although that seems to be limited in the winter up there.