By Suzanne A. Marshall from the May 2012 Edition

A few weeks ago a couple of our friends offered to take us on a jaunt down the highway to see the countryside and go exploring. We jumped at the chance since we do not have the luxury of a vehicle here in Manzanillo as yet. So the four of us jumped in the car and headed south toward

Cuyutlan with no plan whatsoever. It was suggested that we might want to see a place where they produce handmade bricks. Sure, why not?

Near a small town called Armeria we turn into a dry dusty driveway and there on the land I see long flat rows and stacks of thousands of bricks. But where is the facility or factory where these are produced and formed? There isn’t one, just a small wooden structure, mounds of soil, a few wheel barrows, shovels, a couple of trucks and hardworking men. The production takes place on the wide open land. Unbelievable! My interest as a story hound is immediately peeked. We ask if we can tour around and my husband Allan grabs his trusty camera.

A few days later, always a researcher, I discover that the production and process of making bricks dates back to ancient Egyptian times when bricks were used extensively. The bible contains the earliest written record of brick production. They were used in building the Tower of Babel and the Egyptians, the ancient Assyrians, Chinese and Romans used brick as well. Parts of the Great Wall of China used brick which dates back to the 3rd century B.C.

So What (?) you may say. I had no idea the process seen near Armeria still encompasses the same methods as old as time. I find this astonishing and incredibly resourceful when compared to the evolution of mass production techniques throughout the world. Hats off to the ingenuity of our forefathers, they had it right from the very beginning and the tradition still goes on.

Almost all construction in Manzanillo is made with these local handmade bricks! An average worker can make between 400-500 bricks per day and works six days per week. This is seriously back-breaking work and I continue to be impressed with the incredible resourcefulness of the local people I have observed throughout Manzanillo and the Colima area over the past few years.

Before describing the man-made processes here in Colima, I’d like to offer some insights into the industrialized production of brick products so that the ‘ancient art’ of the local Colima production can be appreciated.

One of Canada’s largest modern manufacturers of brick produces 300 million bricks per year. This is accomplished utilizing massive facilities which receive truckloads of clay mix and use extrusion, moulds, presses, conveyor belts, robotic loaders, dryers and ovens and modern distribution systems.

I found a very interesting history of brickmaking in the USA. Brick was the most prevalent material used for construction until the turn of the 20th century when demand began to dwindle due to a shift of focus on lighter building materials such as glass, aluminum and steel. Veneers were used over poured concrete foundations instead of brick.” In 1835 there was a terrible fire

in New York City: 674 buildings in the Wall Street area were burned, and 13 acres of the financial district devastated. This along with the growing population of America due to immigration, created a tremendous need for building materials.” Business boomed as stronger, fire-proof buildings were in great demand.

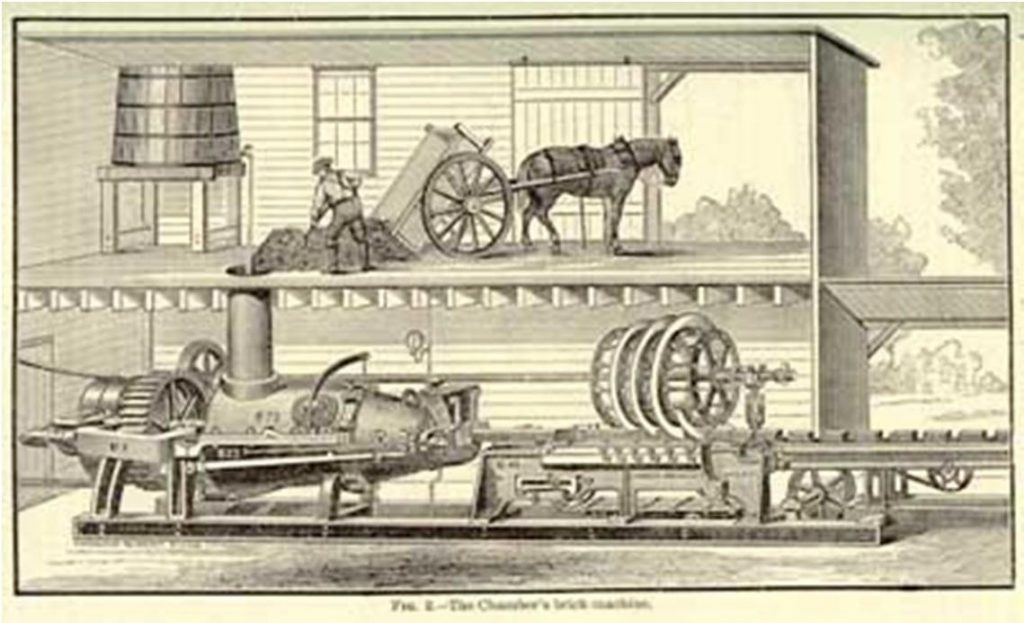

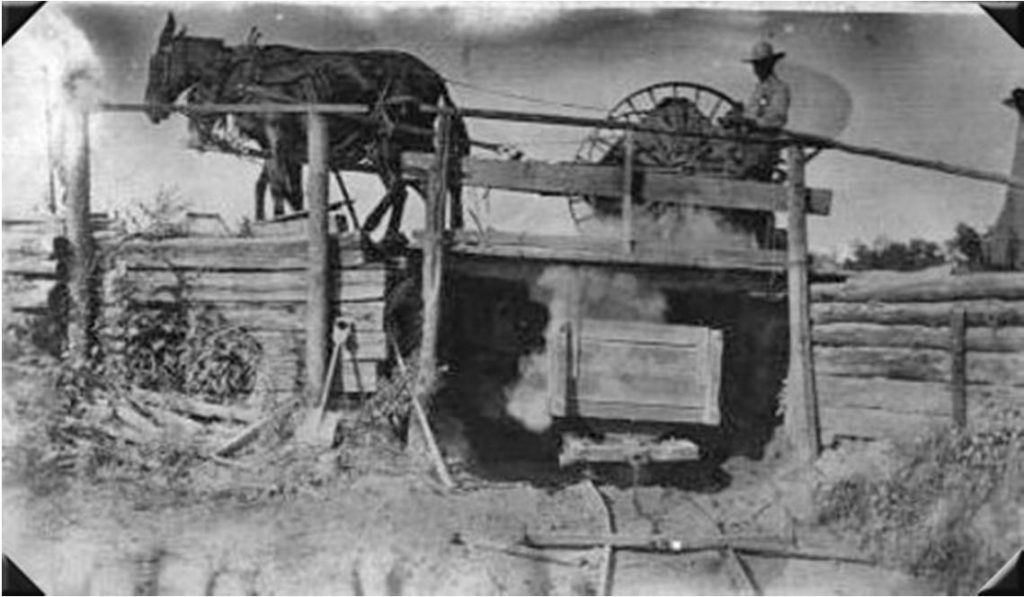

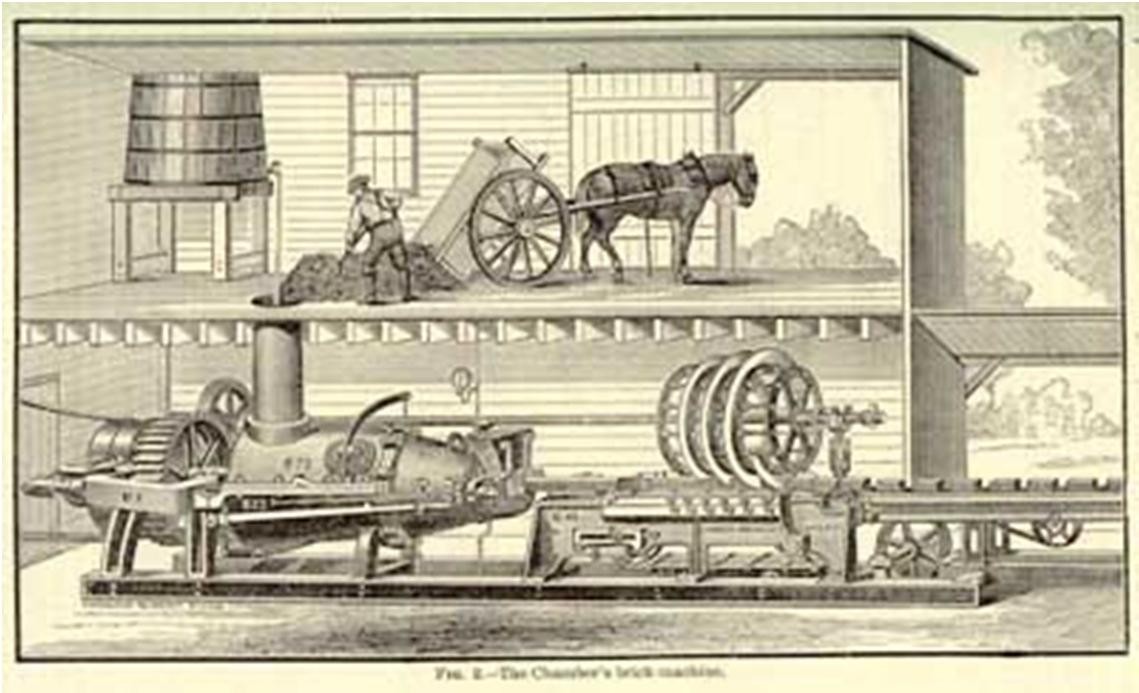

The evolution of the process since the early 1600’s saw a much more industrialized approach in the 1800s as demand grew. From mule and horse teams and crude rail boxes; to horse-driven ‘Pug Mills’ which simultaneously ground clay and water; from hand moulding to moulding machines and conveyor belts; various drying sheds and tunnels with steam-driven fans at each end and stacking techniques that took about 2 weeks for proper drying; then, from kilns made of the stacked dry bricks with fires built inside for baking and finishing(8 to 12 days); and on to modern day ovens and machinery.

I never thought I’d be saying the word ‘wow’ about a little ol’ brick but honestly the process involved is pretty amazing. Now back to present day Armeria, Colima and my fascination with the still ancient craft of brickmaking by hand, with exception for wheel barrows and handmade wooden moulds. In comparison to the foregoing information, what I saw in Armeria was a ‘mind blower’ to use a modern colloquial term. I honestly didn’t realize it until I had done the research.

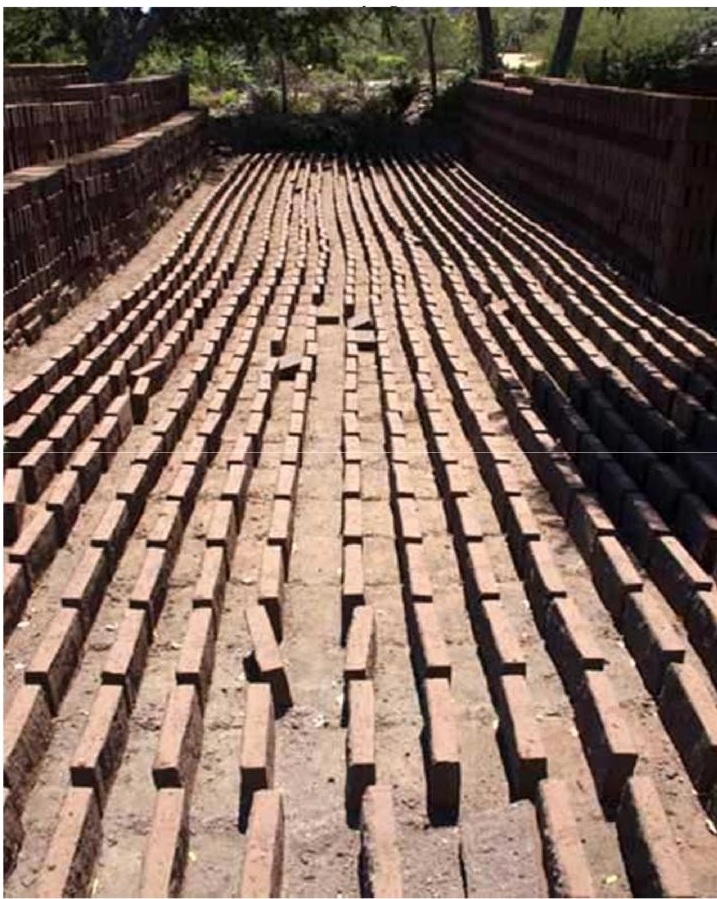

The Colima location is ideal. There is an abundance of the right clays (they vary in color) and inland from the Pacific it is hot and dry. Mounds of clay are shovelled by hand and mixed with well-water to a consistency learned by experience. The one young fellow we watched that day was using a plastic bucket and his feet for mixing. Whatever gets the job done! Next, the mixture is scooped into wooden moulds and scraped off to a smooth flat surface. “Often, the brick-maker will finish off each mould with a flourish—his ‘signature’ or a handprint.” Once set, the mould is removed and sun drying begins.

Sun drying involves laying out row upon row of bricks on to the ground which has been groomed to a smooth flat bed. As the bricks dry, they are repeatedly turned (by hand) edge by edge to prevent warping or misshaping. When they become more stable, the bricks are then stacked into rows 7 or 8 bricks high allowing for ‘breathing’ holes for continued drying. I did not ask how long this process takes but from my research I would presume up to two weeks or more.

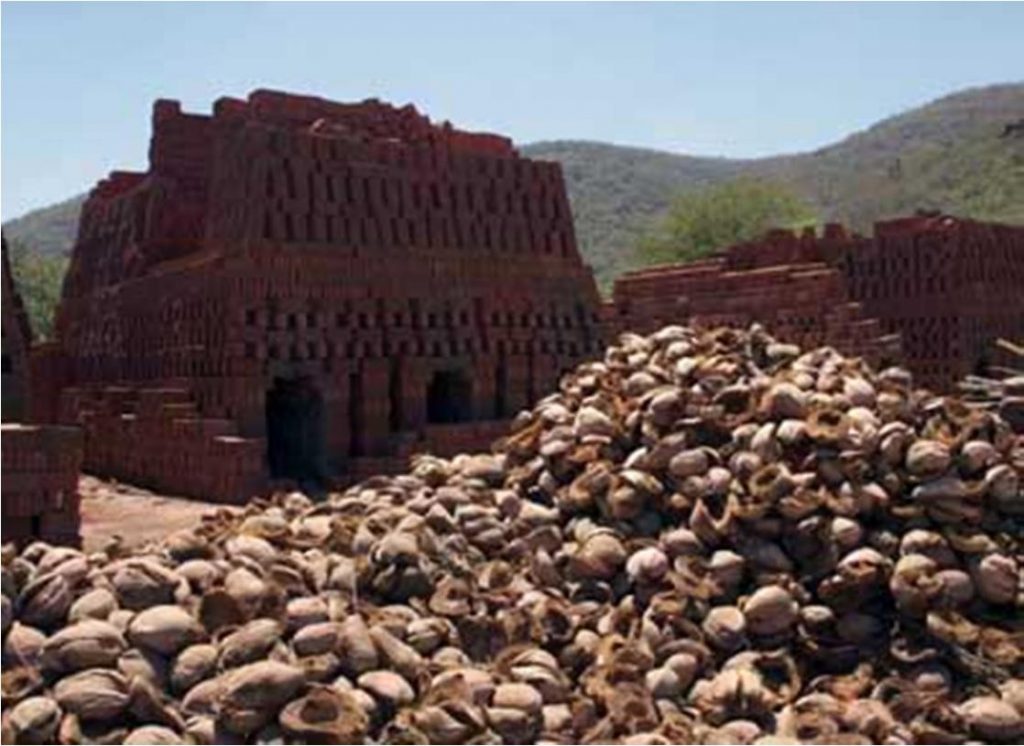

The curing process now begins. The air dried bricks are stacked into mountainous ovens in such a way that an opening and some hollow shafts remain to enable stuffing the firing materials into these self-made ovens to complete the curing process. Can you imagine stacking bricks at all let alone in such a way that a cooking oven is left on the inside and the whole enterprise doesn’t collapse?? Next, these temporary ovens are loaded with burning materials and sealed on all sides with mud. Fires are lit inside then the openings are closed off.

In Armeria we saw large mounds of dry coconut shells which are used for the fires in the ovens. What a brilliant recycling program. The shells burn extremely hot and fast, speeding up the firing process. When the fires burn out and the bricks have cooled they are dismantled and are ready for the various markets.

My last thought about this fascinating ancient process is that it is a really “green” product. In a world of plastic, chemicals and a myriad of pollutants, here we have a product produced in every aspect ‘from the land’ that will last for centuries. It doesn’t get much better than that.

Sources:

- Armeria photos by: Allan Yanitski

- hubpages.com/hub/history-of-the-brick

- http://www.bramptonbrick.com

- http://brickcollecting.com/history.htm

- gomanzanillo.com/features/bricks/index.htm

Download the full edition or view it online

—

Suzanne A. Marshall hails from western Canada and has been living the good life in Manzanillo over the past 8 years. She is a wife, mom and grandma. She is retired from executive business management where her writing skills focused on bureaucratic policy, marketing and business newsletters. Now she shares the fun and joy of writing about everyday life experiences in beautiful Manzanillo, Mexico, the country, its people, the places and the events.

You must be logged in to post a comment.